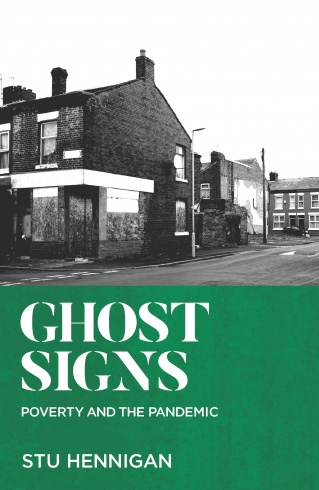

Mike Phipps reviews Ghost Signs: Poverty and the Pandemic, by Stu Hennigan, published by Bluemoose

When the coronavirus pandemic hit Leeds, the Council set up a food distribution centre and a helpline for residents. Library outreach worker Stu Hennigan jumped at the opportunity to deliver food parcels to people who were self-isolating. By mid-May the Council had delivered over 20,000 parcels.

“Over the course of five months working Friday to Monday, I drove approximately three and a half thousand miles around the city, with the work taking me into the heart of some of the most disadvantaged estates and onto the doorsteps of some of the city’s most vulnerable people. Many of the scenes I saw were horrifying,” reports the author.

A decade of austerity had produced “unbelievable levels of deprivation”, people living in slums, adults “who were literally starving”, “children who looked at everyday food items like they were extravagant birthday gifts”, “people with severe mental health problems abandoned by the state to fend for themselves.” He decided to document what he encountered.

A quarter of all neighbourhoods in Leeds are listed as being in the top 10% of the most deprived areas nationally. Over 150,000 people live in absolute poverty, as do over 50,000 children under 16. It took a pandemic for the author to discover “things that will stay with me forever, plenty of which I hope to never see again.”

The book is written in the form of a diary, starting in April 2020 with Hennigan’s first day as a volunteer, driving around what feels like a ghost town. Some estates he visits look like war zones. Houses have bare walls and splintered floorboards. On his first day, one man tells him he can’t remember when he last ate. Other recipients are grateful to the point of tears.

“When I get to the next address,” reads a typical entry, “the numbering system isn’t great here either, so I decide to look for flats with kicked-in doors as they’re so often the ones I’m delivering to. I manage to identify which block the drop is on, but my strategy is no good as every single window and door has been busted.”

Despite his humanitarian mission, there are occasions when he is threatened with real violence amid the decay and neglect. Some of the recipients are terminally ill, others have severe mental health problems or are wracked by drug addiction – all factors which add the stress of mental exhaustion to the physically demanding work he is doing.

Hennigan has his own family to look after, with small children disoriented and, increasingly, distressed by the requirements of lockdown. His account of his volunteering reads fluently and is full of detail, but he had to jot down his observations in odd moments of respite from the multiple pressures and do the serious writing-up by getting up at 4.30 in the morning.

After four weeks at the job, “there’s no escaping the fact that we’re feeding the poorest of the city and that the virus isn’t coming into the equation at all. The stark reality is that in the present economic climate there are huge swathes of the city’s population… who are unable to feed themselves or their families properly, and the food parcels we are providing are vital to their survival.”

It’s the sheer, repetitive depth of deprivation that grinds the author down and may well surprise the reader. Former Guardian editor Alan Rusbridger hailed the book as “an important act of witness.” It has been compared favourably to George Orwell’s The Road to Wigan Pier and is now on the reading lists of some university courses.

It all takes place against a backdrop of government incompetence and rule-breaking around the pandemic. But ultimately, this book is less about Covid than longer-term destitution. And the people who were so desperate to get food parcels in 2020 are today unable to heat their homes and facing eviction for rent arrears.

Leeds Council closed its food distribution centre after 23 weeks, having delivered nearly 34,000 food parcels. The cost was enormous. With the council facing a potential overspend of nearly £200 million for the financial year 2020-1, more local service cuts loom. This picture is replicated across the country.

Hennigan had more than enough material for his book from the first few weeks of his volunteering and even then he left a great deal out. As he says in the book’s Afterword, “I saw many, many people who appeared to be on the verge of starvation, but there was no way they could all be included.”

Elsewhere he says: “A lot of people are conversant with the stats about poverty… I’m trying to humanise these people and make them real in the eyes of the public, so I would like the people who read it to be angry. I would like them to be upset.” For many, this book will certainly achieve those aims.

Mike Phipps’ new book Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: The Labour Party after Jeremy Corbyn (OR Books, 2022) can be ordered here.