By Simon Pirani

Russia’s war on Ukraine marks a historical turning point. The illegal annexation of four Ukrainian regions in September, and the nuclear threats issued, are a dangerous intensification. It is a matter of principle, in my view, that the labour movement and civil society internationally should support Ukrainian resistance, and I have written about that elsewhere. In this article, I show that, until 2014, western policy was focused on integrating Russia into the world economy on the west’s terms: even after the Kremlin’s military intervention in Ukraine, the western response remained reactive.

The western powers’ limited economic war against Russia is effect, not cause. Their Russia policy has aimed at integrating Russia economically, and making it a junior partner – not an enemy – politically. They have been forced to change by Russia’s imperial assault on Ukraine in February, and by Ukrainian popular resistance to it. In order to understand what happens next, and how this relates to the western powers’ historic failure to deal with climate change, it makes sense to review the history of these relationships.

An approach grounded in Marxism is proposed here, that takes into account both state and political forces, and the economic relationships underlying them. Those in the western ‘left’ who hold that ‘NATO expansion’ is the chief cause of the military conflict (up to and including Russia’s threat to use nuclear weapons), and that Ukraine is fighting a ‘proxy war’ for the US, are both wrong and politically wretched. They act in effect as apologists for the Kremlin’s murderous actions. They ignore the obligation on all who seek to develop a Marxist analysis to uncover concretely howstate and political forces are anchored in economic relationships. So an editorial about the war in Monthly Review, a premier English-language Marxist journal, focuses on “the central role that the US and NATO have played […] from the start”; denies that Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014 (!); and, along with an associated 6800-word article by the journal’s editor, says not one single word about the economic relationship between Russia and international capital. Not one.

Here I offer an alternative explanation that takes into account economic and political factors. I then illustrate it with the specific example of the disputes over the gas trade.

In 1989-91 the Soviet system collapsed, and so too did the two-power system of international regulation that had persisted since 1945. The Soviet Union’s autarchic, state-controlled model had run its course; labour unrest and social movements helped to finish it off. The western powers’ long-time military adversary was in chaos, but even then, neoliberal hegemony expanded into the post-Soviet space not only, or even mainly, by means of NATO.

The most devastating changes were economic. Russia, Ukraine and other former Soviet republics were plunged into the greatest peacetime slump anywhere, ever; swathes of industry were junked; social welfare systems collapsed; working people suffered unemployment and poverty. Western capital did not always seize property, or try to. Russia’s oil, gas, minerals and metals industries were mostly transferred into the hands of domestic business groups founded by canny former bureaucrats. So were Ukrainian steel, coal and chemicals. The drive from the west was to break up state property and trash every obstacle to the working of markets.

The most significant round of NATO expansion belongs to this first post-Soviet period. In 1999, Hungary, Poland and Czechia joined, and plans for accession were agreed with Bulgaria, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia. They all joined in 2004. Since then four small Balkan nations have joined NATO (Albania and Croatia in 2009, Montenegro in 2017 and North Macedonia in 2020); as for Ukraine, while NATO countries long supplied it with relatively small quantities of defensive weapons, no accession plan was begun. Some Washington-centric ‘leftists’ portray the US as the only driver of this process; in reality, eastern European states that had repeated historical experience of being invaded by Russia, and none of being invaded by the US, were themselves actors.

Putin’s accession to the presidency in 2000 marked a turning point. The Russian state was rescued from the chaos of the 1990s. The business groups were disciplined and forced to pay tax. Riches were taken from the Yeltsin-era oligarchs and put under the control of the former security services officers (siloviki); the assets of the largest privately-owned oil company, Yukos, were confiscated and handed to state-controlled Rosneft. As oil prices rose, to peak in 2009, Russian capitalism boomed as never before or since. Significant steps were taken to merge Russian capital with western markets, including financial sector development and the sale of minority shareholdings in materials exporters to foreign owners.

With Russia’s second war on Chechnya (1999-2002), Putin – enthusiastically supported by NATO – staked his claim as a gendarme for capital in Russia’s sphere of influence. The NATO powers were less happy with his first military adventure outside Russia’s borders, the invasion of Georgia in 2008, but turned a blind eye. Government attention moved elsewhere: a few weeks later, the financial crash unfolded in the US.

The post-2008 economic downturn formed the backdrop to the Maidan uprising that overthrew Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych in 2014. Improvements made in the 2000s to Ukrainian living standards had been wiped out. No single cause brought people out on to the streets, but resentment at the corruption of Yanukovych and the eastern Ukrainian bourgeoisie (owners of mines, steelworks and manufacturing capacity) that he represented was a factor. So was the push by other elements in Ukraine’s ruling elite for closer links with Europe and political distance from Russia. The description by Monthly Review and others of these events – in which millions of people participated and during which the police force collapsed – as a ‘coup’ is as irrational as it is politically slanted.

The Kremlin’s decision to intervene militarily in Ukraine in 2014, and to annex Crimea, was provoked firstly by fear that the chaotic movement that swept away Yanukovich could be replicated in Russia. Putin had already faced the first large-scale protest movement of his presidency against ballot-rigging in the elections of 2011-12. Frustration at the Ukrainian ruling elite’s closer links with Europe was also a factor. NATO’s limits were tested.

Even after 2014, the western powers amended, but did not abandon, their approach. While the US and its allies were determined to place limits on Russia’s military ambitions, it remained a gendarme in the former Soviet space. The western powers imposed sanctions that undid years of work by Russian companies to integrate more closely with the world financial system; Russian economists’ hopes of diversifying from dependence on hydrocarbons were dashed. But Russia’s functions as a supplier of oil, gas and metals to the world market, and of flight capital to offshore zones, was largely untouched.

The narrative of ‘NATO expansion’ does not fit with the most basic facts. During Putin’s next military adventure, in Syria in 2015-16, ‘red lines’ laid down by the US administration were clearly crossed by Russia and its Syrian ally. NATO’s failure to respond was humiliating. Russia spent several more years in the economic doldrums; Putin’s hopes that the new Ukrainian president, Zelensky, would prove more pliable in negotiations over the Donbas than his predecessor, were not realised; only then did Putin move to a more extreme form of near-fascist militarism and order the 24th February invasion.

Only after that, and only after Putin’s hopes of rapidly taking Kyiv were undone by Ukrainian resistance, did the western powers abandon their previous policy of strictly limiting arms supplies for Ukraine. As the Ukrainian writer Oleksiy Radynski argues: “An informal agreement between two imperialist powers [Russia and Germany] has been thrown into disarray by one factor that remained out of reach of these imperial designs: Ukraine’s popular resistance.”

The gas trade

The gas trade, long central to Russia’s economic relationships with both Ukraine and Europe, is now falling victim to the economic war. Here I review its history, to see what light can be shed on the causes of conflict, both military and economic. (This was a principal area of my research during 15 years at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, up to last year.)

Ukraine entered the post-Soviet period as (i) the transit route for gas from Russia’s giant Siberian fields to European customers, and (ii) a major consumer of gas, Gazprom’s second largest export market after Germany. From 1992, payment by Ukraine for gas consumed, and by Russia for gas transit through Ukraine to Europe, formerly settled by intra-Soviet accounting transfers, overnight became payable in dollars. The Russia-Ukraine ‘gas wars’ began, centred on unpaid bills for gas consumed. In the 2000s, as both economies recovered, the value of gas sales to Ukraine for Gazprom, and of transit fees for Ukraine, increased significantly. At first, Russia sought to control both transit and the Ukrainian market – but by the 2010s had abandoned both those aims.

First: what does this story tell us about Russian political and economic strategy towards Ukraine? In the 2000s, as the Ukrainian political pendulum swung back and forth between pro-European and pro-Russian politicians, Gazprom focused on securing control over the Ukrainian transit system. Ultimately, the Ukrainian parliament blocked all proposals for joint ownership. Gazprom reacted by driving a tough bargain on the price and contractual terms for Russian gas exports to Ukraine; this led in January 2009 to the most serious ‘gas war’ yet, when flows not only to Ukraine but to Gazprom’s European customers were cut off.

After that dispute, the Russian approach changed. Attempts to involve Russian-controlled companies in the Ukrainian domestic market and in transiting gas were abandoned. Instead of seeking commercial concessions, Russia sought political ones. In 2010, Russia swapped cheaper gas for an extension of Ukraine’s lease to Russia of its naval base in Crimea. In 2013, the Kremlin offered a substantial discount on gas sales as part of a generous trade package, conditional on Ukraine abandoning its talks on an association agreement with the EU; Yanukovych’s support for that package was among the sparks that set off the Maidan revolt. In 2016, in response to Russia’s military activity in eastern Ukraine, the national gas company Naftogaz Ukrainy ceased direct purchases of Russian gas all together.

In the 2000s Russia had held out hopes of profiting from its powerful position in the Ukrainian gas sector; in the 2010s it sacrificed those hopes in pursuit of territorial gain.

What about Russian strategy towards European governments and companies? After the January 2009 dispute, Gazprom prioritised construction of pipelines to bring gas to Europe by non-Ukrainian routes. It aimed to rid itself of dependence on transit through Ukraine at all costs: the decision to go ahead with Nord Stream 1, directly from the Baltic Sea to Germany, was taken in 2010 despite the onset of the worst recession since the 1930s. Most of the powerful European energy companies that bought Russian gas saw Ukraine as mostly to blame for the cut-off in January 2009, and approved, or joined in, this project.

Throughout the 2010s, there were tensions between Russia and Europe over gas: this was not about Ukraine, though, but about the EU’s market rules, which cut across the traditional oil-linked long-term contracts that Gazprom and its big customers preferred. In other words, it was about the terms on which Russia, as a raw materials exporter, would supply world markets – a relationship both sides sought to continue.

Finally, what about western governments’ and companies’ strategies towards Russia? Surely, if western threats were the dominant factor stoking military conflict, the major oil companies would at least bear that in mind. But both before and after 2014 they invested billions in projects in Russian upstream projects; Ukraine, seen as having less favourable terms of entry, was to all intents and purposes ignored. The biggest ownership deal ever between western and Russian oil companies, BP’s swap of its shareholding in TNK-BP for 20% of Rosneft, went through in 2013. Rosneft, and its politically powerful chairman Igor Sechin, were sanctioned by the US in 2014 after Russia’s annexation of Crimea; BP’s cooperation with Rosneft continued and deepened.

The 2014 US sanctions did threaten the Nord Stream 2 project, that aimed to complete the diversification of gas transit away from Ukraine. Germany, though, wanted the pipeline to be completed. After lengthy negotiations, in July 2021 – with the Russian troop build-up on Ukraine’s borders well underway – Germany and the US concluded a deal under which the sanctions on the pipeline were dropped, in exchange for German commitments of investment in Ukraine. This action by two NATO powers was predicated on the assumption that efforts to profit from Russia’s resources – by means of business relationships with Russian companies, rather than offensive military action – would continue. This attitude changed only on 22 February, after the Kremlin had recognised the two separatist ‘republics’ in the Donbas, and the German government blocked completion of the pipeline.

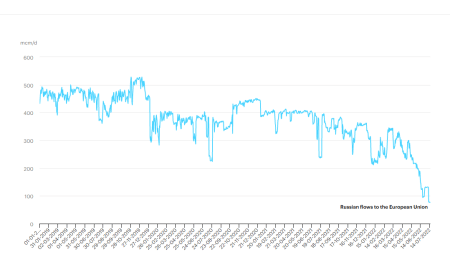

Following the damage to the pipeline by sabotage in September, it seems doubtful it will ever be resurrected. Some of Putin’s apologists in the western ‘left’ hurried to blame the US for the damage, despite having no evidence one way or the other. What is certain, though, is that their claims that the sabotage cut across Gazprom’s commercial interests are baseless. Gazprom’s entire European sales business, built up painstakingly over half a century, had already been wrecked, over the summer – by the Kremlin, when it ordered gas shipments to be reduced, in its attempt to weaken European military and political support for Ukraine.

Simon Pirani is honorary professor at the University of Durham and writes a blog at peoplenature.org. This is an excerpt from a longer article, published here that looks at the breakdown of economic relations between the western powers and Russia as a result of Russia’s war on Ukraine; the extent and limitations of western sanctions; and the so called ‘energy crisis’ and its implications for tackling climate change. It was commissioned by Emanzipation journal, who will publish a German translation, and is reproduced here with thanks to them.

Image: . Press Service of the Ministry of Defense of Ukraine. Source: «PULSE NEWS» 21 February 2015. Author: An authorized Youtube stream of the STRC Ukrainian television and radio broadcasting «UTR – TV channel, licensed under the Creative CommonsAttribution 3.0 Unported license.

[…] Pirani, “The causes of the war in Ukraine”, Labour Hub, […]