By Liz Davies

I’m inspired to write some memories of my involvement in what was then Labour Briefing or Labour Left Briefing after reports this summer that one of its twin progeny – Labour Briefing (LRC) magazine – had ceased publication and would focus on visual media. The remaining Labour Briefing Co-operative is still going strong. A collapse is unsurprising since the original Briefing split ten years ago, in circumstances that, for those of us on the outside, were impossible to understand.

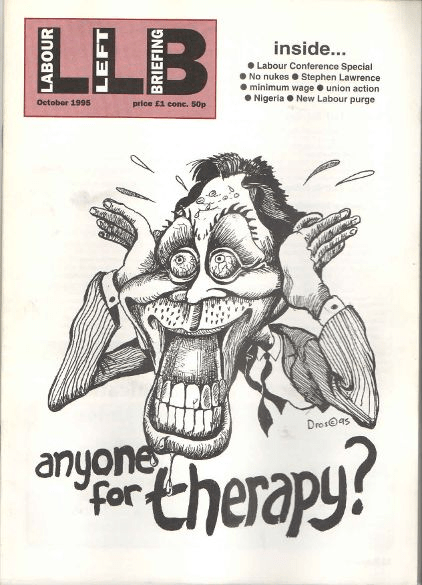

There is a detailed history to be written about the magazine that began as London Labour Briefing in 1979, spawned various regional Labour Briefings (including Brighton, Oxford and Exeter), re-launched as Labour Briefing in 1990, re-named itself Labour Left Briefing in 1995 and then split in 2012. The masthead during the 1990s summed up Briefing’s politics: “The voice of Labour’s independent unrepentant left” (emphasis in original).

Labour Hub has published two contributors’ recollections of the earlier Briefing – Mike Phipps’ and Jon Rogers’ The Labour Briefing we remember. I hope it will publish more.

My focus, though, is not the detailed history but a more personal account. For me, the history of Labour Briefing, or “Briefing”, is very personal indeed. I met my two life partners – my late partner Mike Marqusee and my current partner Kevin Flack – through it. Briefing was one of the causes – not the exclusive cause – of my 15 minutes of infamy when I was democratically selected as a Labour Parliamentary candidate but then blocked by Labour leader Tony Blair on the grounds that I was too left wing.

My involvement began in 1989, and more intensively in 1990 when I became a Co-Chair of the Editorial Board of a re-launched Labour Briefing. Mike Marqusee was appointed editor (the sole paid job, albeit paid at a part-time pittance).

I had encountered London Labour Briefing for over ten years before I became involved. I can’t have been the only 17 year young socialist who was not expecting to encounter a pamphlet entitled My Sex Life at a Labour Party Young Socialists Conference, and I read it, open-mouthed at its frankness. I followed the detailed – oh, so detailed – reports of Labour Party General Management Committee (as they then were) meetings in various London constituencies.

Briefing combined socialist values, a belief in the accountability of elected representatives, leading to those detailed reports, and an embrace of the liberation struggles of women, black people, lesbians and gay men (as the movement was called in the 1980s) and people with disabilities. Briefing understood that socialism and liberation struggles go hand-in-hand and there is no hierarchy between those different struggles. They are best, and strongest, when combined together. We would now call that concept “intersectionality”. And, thankfully, Briefing also had a sense of humour, so often lacking on the left then as now.

So, when I started to go to its meetings and to write for it in 1988-1989, I was very pleased to join the Editorial Board. Briefing felt like my natural home.

Under Mike Marqusee’s editorship, Briefing developed important journalist principles. Contributors could disagree with each other – indeed that was encouraged: we would be embarrassed when we spoke with the same voice. Mike wanted the magazine to feature diverse writers, with lived experience. He was a sensitive commissioner and editor, making sure that an activist’s voice could be heard through their writing, especially if writing was not the thing they were best at.

Mike believed in “punching up, not punching down” so the regular feature ‘Class Traitor of the Month’ was aimed at the powerful – those in roles leading the Party and trade unions – not activists on the frontline. Briefing’s aim was to “pick on someone stronger than ourselves,” Mike would say. ‘Class Traitor of the Month’ pulled no punches about those public figures’ political actions and statements, holding them to account, but it never strayed into gossip about their personal lives, or their appearance.

Briefing had an influence, thanks not least to the infamy of ‘Class Traitor of the Month’, well beyond our resources. The Editorial Board consisted of about 15 – 20 people, chaired during my time by combinations of myself, Sue Lukes, Dorothy Macedo and the late Leonora Lloyd.

Production happened every four weeks, over a long weekend. I have fond memories of those Friday evenings at Graham Bash’s house, when we would debate important editorial decisions (what font to use, the precise page order and layout) over a take-away. An unsung hero is stalwart Dave Lewney who arrived every four weeks from Brighton to lay out the paper, not leaving until it was done, and carried on with that task for decades. Kevin Flack sometimes brought his children, and they and I would watch TV together. It’s hard to remember or fully appreciate nowadays the logistics involved in collating all the articles commissioned, delivered through the post or by hand,, typing them up, sometimes struggling with handwriting, and laying them out.

We really got under the skin of the Labour Party powerful. Generally people would rise above being called ‘Class Traitor of the Month’ or even treat it as an accolade. Every now and then, a cross letter would arrive, which we happily published. We also heard, on the grapevine, about prominent Labour Party figures disappointed that they were never featured.

Holding people to account, through satire, is a great political tradition.

Chickens came home to roost for me in 1995, when I had won a parliamentary selection in Leeds North East. News travelled fast to Blairite members of Islington Council, where I was a Labour Councillor and they decided to try and block me. They had access to Blair who readily agreed, as it allowed him to treat the Campaign Group of MPs as a sealed tomb. Blair was stuck with Tony Benn, Jeremy Corbyn, Diane Abbott and others as Labour Members of Parliament but was determined not to let others in.

All hell was let loose – I and Briefing were described in terms that suggested that we would unleash the apocalypse. I remember being described as a “cancer in the Party”. None of the accusations stuck – the NEC voted not to endorse me but refused to give any reasons. The press had a merry time: “Didn’t you call your leaders class traitors?” Michael Crick shouted at me. I would hold up that month’s issue of Briefing, with a cartoon of Blair by the brilliant Gary Drostle on the front page and say, patiently, “It’s a cartoon; it’s a joke.”

While I was taking the flak, Briefing comrades looked after me. They escorted me around meetings, made sure I was fed during an intense Labour Party conference, prevented the press from tracking me, guarded the women’s loo where I escaped from a coterie of solely male photographers. We were a diverse group, but we had solid emotional and political bonds, proving that the personal is political.

Three years later, I ran for the National Executive Committee on the first ever Centre Left Grassroots Alliance slate. The powers that be in the Labour Party regurgitated most of the slurs from 1995, but Labour Party members, exercising One Member One Vote, were not convinced and voted for four of the six CLGA candidates, including myself. The members had spoken, and I was vindicated.

By the mid-1990s, Mike had ceased to be the editor, and became the magazine’s political correspondent instead. That freed him to write more discursive, personal pieces. Although Mike also wrote for Tribune, New Statesman, Red Pepper and elsewhere, Briefing gave him a free rein to write on whatever he liked, reflecting his diverse interests: racism in cricket, the struggle against communalism in India, the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s.

The two subjects that stand out for me are Voices for Rushdie, co-founded by Mike in response to the Salman Rushdie fatwa in 1989, defending freedom of expression from an anti-racist perspective, a stance that many of the left shied away from at the time. And his article, ‘The Sleep of Reason Breeds Monsters’, published shortly after the death of Diana in 1997, spoke common sense for us republicans silenced at the time:

“Let’s start with some simple propositions. First the institution of the monarchy and the broader principle of inherited status are irrational and incompatible with a democratic society. Second, whatever her merits, Diana Spencer’s contribution to public life did not justify the reaction to her death, which was disproportioanate by any sober criteria. For a week, both these eminently reasonable propositions were banned from discourse. Diana-sceptics were bullied into silence. It was an alienating and at times frightening spectacle and a lesson in what the media, state and church can achieve when all are on message… If that is maturity, I’ll stick to adolescence.”

In 1999 Mike left the Labour Party and I followed in 2000. We ceased to be involved in Briefing, in circumstances I regret. True to its principles, Briefing gave Mike the space to write about his decision to leave the Labour Party: ‘A challenge to our readers: what will you do in 2001?’

I returned to the Labour Party in 2015, when Jeremy Corbyn was running for leader. Unexpected things happen in politics – which is why I should not have left – but no one had said to me in 2000 that, if I stayed in, Jeremy Corbyn would become Leader. It felt like coming home, to the Party and to the Labour left.

But Briefing was a shadow of its former self, having split into two. Each magazine was still determinedly produced every four weeks by dedicated volunteers, not least Graham Bash and Mike Phipps for Labour Briefing (LRC) and originally Jenny Fisher, Christine Shawcroft and John Stewart for Labour Briefing Co-operative. And its backbench Labour MP columnists were suddenly Leader of the Opposition, Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer and Shadow Home Secretary. Was it Briefing’s political moment?

Somehow, despite Briefing’s political approach –unrepentantly socialist, democratic, feminist, anti-racist and pluralist – having been vindicated by Corbyn’s election, it could not speak to all those young activists flocking into the Labour Party, inspired by Corbyn. The closest reincarnation of the early Briefing is perhaps Momentum when it was at its best: youthful, irreverent, funny, insistent on Labour Party democracy and accountability, balancing Labour Party activity with direct action and protest outside the Labour Party.

A movement remains of independent and above all unrepentant socialists, expressed through different outlets and social media these days. I like to think that Briefing kept that flag flying through dark days for the Labour left.

Liz Davies KC is a barrister specialising in housing and homelessness law. She was an elected member of Labour’s National Executive Committee (1998 – 2000).