By Bryn Griffiths

Forty years ago, in February 1982, ten people published a trial edition of Brighton Labour Briefing and they asked on its front page: “Why Brighton Labour Briefing?” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 1, February 1982).

Later that month, seventy people packed into a room in the Eagle Pub in Brighton, to answer the question they had been set. What followed, as the magazine established itself, was a rich seam of gold which the Labour left can all mine for lessons today.

The circumstances, like today, were tough for the left. The Labour left’s high point had occurred on 27th September 1981 when Denis Healey, who had been the UK’s first neoliberal Chancellor, pipped Tony Benn to Labour’s Deputy Leadership post by a fraction of a percentage point.

With the right wing in the saddle, and Michael Foot as leader a willing prisoner, the context we faced was a Labour Party in which Peter Tatchell had been removed as the Labour candidate for Bermondsey. The witch hunt was bearing down on the Militant Tendency and Tariq Ali had been refused entry to the Party. Healey had just announced he would not serve in a Labour Cabinet if it was committed to nuclear disarmament. The situation in the Party was going to get a whole lot worse but it already felt pretty bad. The situation in the 2022 Labour Party today is nothing new: I am afraid Labour left veterans have seen it all before.

What attracted seventy Labour Party activists to the Eagle pub launch meeting was a curiosity about a new group that promised to do politics differently. The new magazine was to be broad, pluralist and a notice board of the left. We wanted to set about building alliances and creating coalitions rather than making enemies! Anyone could attend its meetings and everyone had a right of reply. In the front-page article “Why Labour Briefing?” the authors proudly announced:

“It is in the spirit of the London Labour Briefing that we intend to work and to organise: it has, to use a popular phrase, ‘broken the mould’ of empty sloganising and jargonised language. Editorial comment is kept to a minimum and written by those activists who attend the fully publicised and open meetings. Articles written by individual Party members are never subjected to political censorship. There is an automatic right of reply. We see ourselves as part of the national network of Briefing groups being set up around the country.” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 1, February 1982).

Brighton Labour Briefing’s openness was crucial to its success, earning trust and the respect of Brighton activists inside and outside the Labour Party. We made a virtue of parading our differences and had debates which was something of a revelation to those scarred by the dead hand of the Leninist tradition. We believed that the magazine could make the left materially stronger by always trying to build alliances locally rather than constantly seeking out the latest heretic.

The ‘noticeboard of the left’ role had the effect of showing left activists how strong we really were and how many others shared our politics. We placed more emphasis on the power of information than the need for ever narrower ideological clarification. However, our attitude to the right wing leadership ensconced in Walworth Road, Labour’s HQ at the time, was rather different and less forgiving!

During Brighton Labour Briefing’s short life, we faced major tests for our political method so our legacy is best understood by looking at how we responded to the big moments of the period. The four big moments I have chosen are the Falklands War, the 1983 General Election, the Miners’ strike of 1984-85 and the Brighton Bombing in 1984.

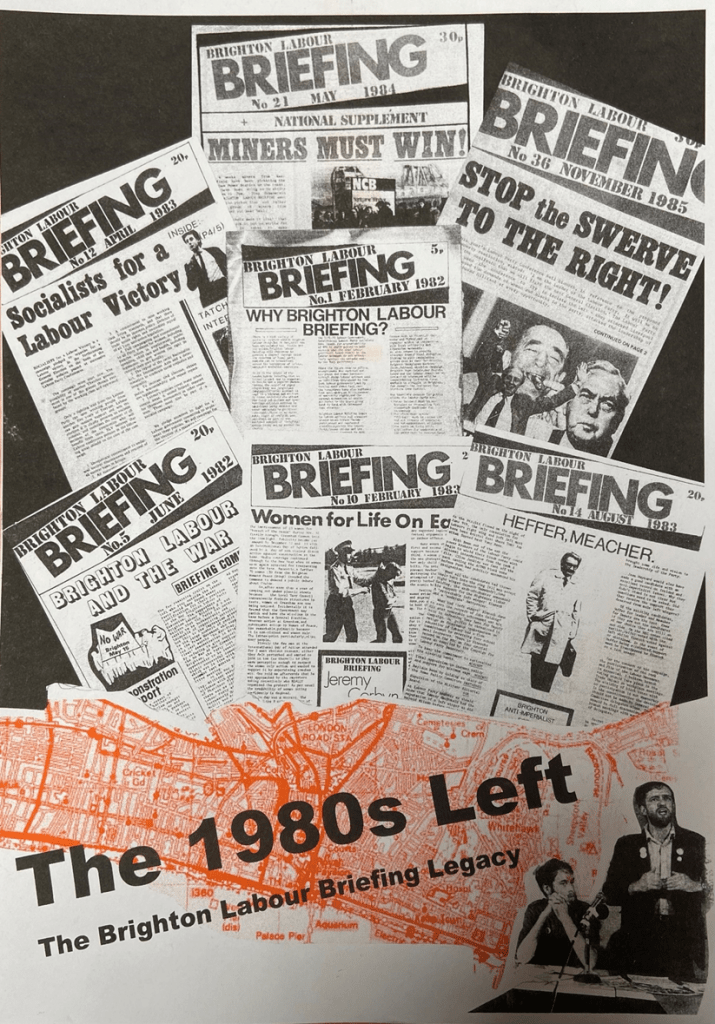

A photomontage of some of Brighton Labour Briefing’s key moments, by Bryn Griffiths. The author is pictured in the bottom corner alongside Jeremy Corbyn MP at the Labour Briefing conference fringe meeting of 1984.

The Falklands war

The Falklands war was a huge issue in the 1980s Labour Party. The Argentinian military dictator, General Galtieri, faced with political difficulties on the home front, invaded the Falkland Islands to help shore up his political position. It was odd that the Malvinas, as the Argentines called them, were British given they were on the other side of the world and he hoped a bit of nationalistic posturing would do him good. Thatcher responded by adopting a full-on Churchillian response to the ‘defence’ of an island nobody had heard of before the naval fleet was despatched. Tony Benn responded, as any reasonable person would, with calls for a negotiated settlement and the involvement of the United Nations. The Labour Leader, Michael Foot, had other ideas. Brighton Labour Briefing wrote:

“Jingoists in the leadership of our own party accuse the left of an abject defeatism in the face of a fascist junta. Certainly, there is an abject defeatism involved here.

But not on the part of the left. Abjectly, with hardly more than a shot fired in debate (‘Bring in the UN. But not now. Maybe the day after tomorrow.’) Labour’s official spokespersons have crumbled, indeed collapsed, before the fait accompli of a British fleet steaming ahead to defend its rocky remnant of Empire. This is political defeatism.

“But already the ideological struggle to create an independent working-class and socialist response is underway. Not only from Tony Benn, Judith Hart and our European Members of Parliament, but also from within Brighton Labour Party.

“At a meeting of Queen’s Park Ward, a motion, to be forwarded to GMC [General Management Committee], called for an end to Labour-Tory co-operation in the crisis, British military withdrawal, and castigated the ‘colonialist adventurism’. The motion gained over 20 votes and was, in fact, passed nem. Con.”(Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 5, June 1982).

We had passed our first big test with flying colours, but what came next was our first attempt to build alliances in practice to strengthen the anti-war movement. First, we won the debate in the Brighton Labour Party that our stance should be “no war; stop the fleet”. Then we helped organise a successful demonstration with the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, local churches, women’s groups and students’ unions. Within our own group and amongst our allies there were political differences, on the characterisation of the Argentinian dictatorship, different views of pacifism and the legitimacy of the Argentinian claim, but we all united in action to protest and say “No War. Stop the Fleet”.

In the Brighton Labour Party, the politics became more complicated when, despite local Party policy, the Executive Committee refused to back the protest. We wrote:

“The supporters of Labour Briefing do not believe that the Party has necessarily to be bureaucratic and incapable of organising activity but this is the impression given to the large numbers of people in the Peace Movement who supported last month’s ‘No War – Stop The Fleet’ demonstration in Brighton.

“By refusing to give support to the No War Ad Hoc Committee in Brighton, the Party lost a unique opportunity to be involved in a highly successful demonstration which was in line with 3 motions passed at last month’s General Committee meeting…

“At the May Executive meeting, Militant struck up an unholy alliance with people in favour of Thatcher’s fleet to ensure there was no official Brighton Labour Party at the march…

“Ray Apps, a leading Militant supporter made the accusation at the EC meeting that the march would support Argentina, he stated at least 5 of the organisations supported Argentina, when challenged he declined to state exactly which Church, Peace or Women’s Group he meant.” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 6, July 1982).

The Militant Tendency failed to oppose the war while others on the left adopted the absurd stance of not working with anyone who did not back their support for the Argentinian claim. Brighton Labour Briefing had prioritised unity in action to stop the war. Our credentials were further established.

Brighton Labour Briefing did not pull its punches with regard to Michael Foot. In an article entitled “Foot Sticks the Boot in”, we wrote:

“As news of Thatcher’s victory in the Malvinas was announced in the Commons Foot offered his ‘congratulations’ to the Tory government. A government which can spend millions on an imperialist adventure which results in hundreds of deaths whilst refusing to pay the nurses is not worthy of the Labour Leader’s support. Michael Foot’s leadership is normally and finally vacillating, incoherent and above all unconvincing, but to align oneself with the Tories is unforgiveable.” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 6, July 1982).

The cartoon we published spelt out the problem: Foot was an inveterate peace monger except in times of war.

The 1983 General Election

Our next challenge was how we were going to approach the 1983 General Election. It was obvious to any fool that we wanted Labour to defeat Margaret Thatcher’s Tories. But, then as now, the Labour leadership were not an attractive proposition. In our tenth edition we announced that Jeremy Corbyn, a National Union of Public Employees (a forerunner of today’s UNISON) full timer and Labour Briefing supporter, was to address our next public meeting. Jeremy was a prospective parliamentary candidate in Islington North and he looked like the kind of Labour MP we wanted!

In our sixth edition we wrote:

“Class struggle cannot be called off for the duration of an election year, the fight against the witch hunt and the attack on socialist policy cannot be ignored. Indeed, our task is as always – to organise the most militant sections of the Labour Movement.

“The strategy of the left in this General Election should be to organise behind conference policy. We must say to people ‘vote for Labour, but prepare to fight’. A campaign by CLP’s, Trade Unions, shop stewards organisations and local left caucuses should be on the streets pointing to the need to develop the Labour Party into a force which can challenge both the Tories and their ruling class paymasters.” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 11, March 1983).

Today some on the left are struggling with the notion of remaining in the Labour Party and campaigning for a Labour victory. Our approach in 1983 focused us on the immediate task of defeating Thatcher while refusing to put our support for the struggles, that were actually taking place, on ice. The April 1983 edition of Brighton Labour Briefing led with the headline “Socialists for a Labour Victory” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 11, March 1983), but inside, in line with our open editorial policy, we allowed a local Party member to put the case for “keeping our mouths shut” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 11, March 1983)for the election period. In the May 1983 edition, we also announced a Socialists for a Labour Victory meeting with a Greenham Common peace campaigner, the late Stan Thorne MP, a former militant trade unionist, and the Brighton Pavilion Labour candidate (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 13, May 1983).

The Socialists for a Labour Victory approach demonstrated how it is not only possible to support Labour, while supporting local struggles and challenging the leadership: it is essential. Supporters of the Breakthrough Party, the Northern Independence Party, the Socialist Labour Party and the Trade Union and Socialist Coalition, please take note. There is more to socialist strategy than vying with the Monster Raving Loony Party to avoid last place.

The miners’ strike

The biggest moment in Brighton Labour Briefing’s short life was the miners’ strike: the great strike of 1984-85. Early in the strike, Brighton Labour Briefing supporters visited the local miners’ picket at Shoreham and in May 1984 our front page led with “Miners Must Win”.

By the summer of 1984, it was clear that the strike was going to be a long war of attrition and leaving solidarity to the local Trades Council would not be enough. Brighton Labour Briefing supporters took a motion to the local Party to set up a Brighton Labour Party Miners’ Support Group and we reported in the magazine that:

“At its General Committee meeting, Brighton Labour Party set up a Miners’ Support Group to complement the activities of the Trades Council.

“The group will attempt to coordinate Labour Party activity in support of the miners and widen the number of people involved beyond the existing activists.” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 23, July 1984).

What followed was an explosion of activity to help sustain the mining communities. Well-attended meetings took place on a weekly basis in the Labour HQ at Lewes Road. The Miners’ Support Group built on the excellent example of the Labour Party Women’s Section and organised food collections every Saturday throughout the town which took place every week until the end of the strike.

Each meeting was focused on action – providing accommodation for pickets, organising benefits, attending pickets in Shoreham, holding a fringe meeting at the Trades Union Congress held in the town and sending delegations to the mining villages. The Miners’ Support Group was chaired by myself, a Brighton Labour Briefing supporter, and the activity was so intense we were allocated Dave Newall, a Kent NUM activist who moved into our house.

Brighton Labour Briefing’s coverage was dominated by the strike and as usual the Labour Leadership was found wanting. By October 1984, our front page dubbed the year “Kinnock’s Year of Shame”’. Dave Newall, the Kent miner, was interviewed and when asked about the Labour Party’s support he said:

“I didn’t know we were getting support from Kinnock and the rest. The rank and file of the party is divorced from the leadership on this issue. Fantastic support from the Labour members and no support from the leadership.”

Moving on to the future, Dave Newall of the NUM was clearly focused on the importance of the Labour party. He said:

“We have got to get the Labour Party sorted out and get some decent people in before we ever get the chance of a decent government. We’ve got to make the Labour Party responsive to the workers, one which doesn’t go along with the capitalists.” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 27, December 1984).

The miners’ strike did much to form our politics. Today as the trade unions move into action again, we need to be ready to respond with a similar intensity if the strikes are prolonged. The parallels with today’s encouraging wave of strikes and the Labour leadership’s response are there for all to see.

The Brighton bombing

In the 1980s the British occupation of the North of Ireland was a major issue. Much of the left ignored the situation, as it was deemed too difficult, but Brighton Labour Briefing did not. Opinions differed widely within Brighton Labour Briefing but there was generally a view that partition and occupation were part of the problem and not the solution.

Within the Republican Movement, a current, around the likes of Gerry Adams, Danny Morrison and Martin McGuinness, was emerging that wanted to move beyond military struggle. The Republican Movement was systematically silenced and Brighton Labour Briefing felt that if an opportunity for peace was possible it was our role, on the British left, to give these Republicans an opportunity to start a dialogue with the Labour left. At the time Neil Kinnock, the Labour leader, supported the ban on any Republican voices being heard, but Brighton Labour Briefing was an early advocate of starting a conversation. Alongside left MPs like Joan Maynard, Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn, and campaigns like the Labour Committee on Ireland and the Troops Out Movement, Brighton Labour Briefing sought to establish a dialogue for peace.

The dialogue with Sinn Fein eventually resulted in the Peace Deal which, if it wasn’t for the Iraq War, could have been Blair’s legacy. In November 1982 Brighton Labour Briefing reported on its role at that year’s Labour Conference held in the town:

“The invitation of Gerry Adams and women representatives of Sinn Fein by the Labour Committee on Ireland (LCI) packed out the Corn Exchange at the largest fringe meeting of Labour Party Conference week. In spite of droves of journalists and cameramen present for a lengthy press conference before and throughout the meeting, there was no coverage on local or national TV and only the barest mention of the meeting in the press. What coverage there was concentrated on alleged plots to get Gerry Adams into the LP [Labour Party] conference hall while the Argus seemed to attach symbolic significance to details such as a large black dog lunging at Gerry Adams on his way into the LCI meeting. The content of the speeches made by the representatives was such as to leave the media with nothing condemnatory to say – any coverage without flagrant distortion would have only served to further the cause of Sinn Fein.” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 16, November 1982).

After the meeting Gerry Adams visited the house of a Brighton Labour Briefing supporter to meet local activists and eat a well-earned pizza. The all-important dialogue was being nourished.

The Adams visit was not the end of Brighton Labour Briefing’s coverage of Ireland as articles about the abuse of civil liberties such as strip searches and plastic bullets became a regular feature. Then on 12th October 1984, an event of historic importance occurred in our town when the IRA bombed the Grand Hotel in the middle of the Conservative Party Conference.

Cllr Richard Stanton, a member of the Labour Group on Brighton Council, was a regular contributor to Brighton Labour Briefing and a supporter of the Troops Out Movement. Asked by the Argus, the local Brighton paper, to condemn the bombing he refused to do so, putting the bombing in the context of what he called the fifteen-year British occupation. A full-page article, “The Grand Hotel Bomb – Why I don’t condemn it”appeared in the December 1984 Brighton Labour Briefing edition where Cllr Richard Stanton was able to explain his position. He wrote:

“My statement to the Argus (18/11/84) includes the following: ‘I abhor violence. But I personally feel the Republican movement is entitled to use force against the British State, as part of the war we started.’ I stand by it, every word. I stand by my decision to say it then, publicly.” (Brighton Labour Briefing, No. 27, December 1984).

Not every Brighton Labour Briefing supporter agreed with Cllr Richard Stanton’s stance. I didn’t, for one, but when calls were made to remove him as a local councillor we sprang to his defence. In the July 1985 edition of Brighton Labour Briefing, we issued a “Defend Richard Stanton, No Witch Hunt Editorial Statement”. By August 1985 Brighton Labour Briefing was able to report the local Labour Party’s response to the witch hunt: “Resign Call Crushed”.

The defeat of the attempt to remove Cllr Richard Stanton was not brought about because people agreed with him. Most people did not. It was because the argument was won that different voices on the Irish question should be heard.

The very positive outcome of the dispute was that it was decided to organise a Brighton Labour Party fact-finding delegation to Belfast to find out more for ourselves. I was part of the delegation and we met a wide range of people to inform ourselves. I personally met the Social Democratic and Labour Party, The Official Unionist Party, residents from the Divis Flats, families of those killed by plastic bullets, Sinn Fein and Peoples Democracy.

We all came back with our views on what was actually happening in Ireland completely changed. The legacy of the delegation was the transformation of the discussion of Ireland in Brighton Labour Party. Dialogue and discussion had done its job. Brighton Labour Briefing played a small role in establishing and then defending the dialogue with Sinn Fein which opened the door to peace, which more senior Labour politicians, including Tony Blair and Mo Mowlam, were able to walk through when the Peace Process bore its fruit.

The future

The Brighton Labour Briefing story is about one of many local Briefing magazines. Over time, local magazines came and went, to my knowledge, in London, Merseyside, Devon, Manchester, Strathclyde, West Midlands, Bristol, Nottingham, Oxford, Hull and Stoke. For a period, Brighton Labour Briefing teamed up with Party members from Horsham, Hastings, Hove, Mid-Sussex, Crawley and Lewes.

Over time, the local Briefings faded away and Labour Briefing’s heyday is widely recognised as Mike Marqusee’s stint, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, as editor of a national magazine. Mike was without doubt one of the left’s most outstanding editors but for me the period of local Briefings with a national supplement was the high point of our influence.

Labour Briefing, as a magazine, has recently come to an end although a small splinter group forges on. In the last few years Labour Briefing was a mere shadow of its former self and it had unlearnt all the lessons that had once made it so successful. It lives on as a You Tube channel and no one would ever suggest it was broad, pluralist, a notice board of the left or has any desire to set about building alliances and creating coalitions, rather than making enemies. Its recent coverage of the Labour left’s response to antisemitism came across as the Millwall of the Labour left. For non-football fans, their infamous chant is “Nobody likes us and we don’t care.”

I think I can end on a positive note. The Labour left has more assets at its disposal than at any point in my lifetime. Where once London Labour Briefing inspired local groups across the country, we now have Momentum, the biggest and most impressive Labour left grouping of my lifetime. We may not have a journal but we do have Labour Hub and superb You Tube and Podcast output from the likes of Novara, Double Down News and Owen Jones. The need for long-form discussion is covered by Tribune, Red Pepper and the Left Book Club. The World Transformed has got political education covered and the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy (CLPD) continues to play its important role. Most recently the Labour left’s links with the trade unions have deepened with the creation of Enough is Enough.

The one ingredient we lack today is local media output from local Momentum and Labour left activists.

There’s no point in complaining about the mass media: we must make our own. Could we go full circle? Could Novara, Double Down News and Owen Jones help local groups create their own You Tube and Podcast outlets to complement their brilliant national output? Now that would be a worthwhile project which would most definitely be in the beautiful spirit of Brighton Labour Briefing at its very best.

Bryn Griffiths was a member of Brighton Labour Party and centrally involved in Brighton Labour Briefing throughout the period described in this article. He finished work and came out of political retirement, re-joining the Labour Party, and supports North Essex Momentum. He is also a member of CLPD. This above article is entirely his own but he is grateful for the comments and memories of Kevin Flack, Dave Lewney, Mike Phipps and Liz Davies.