Thirty years on, Mike Phipps revisits the debate

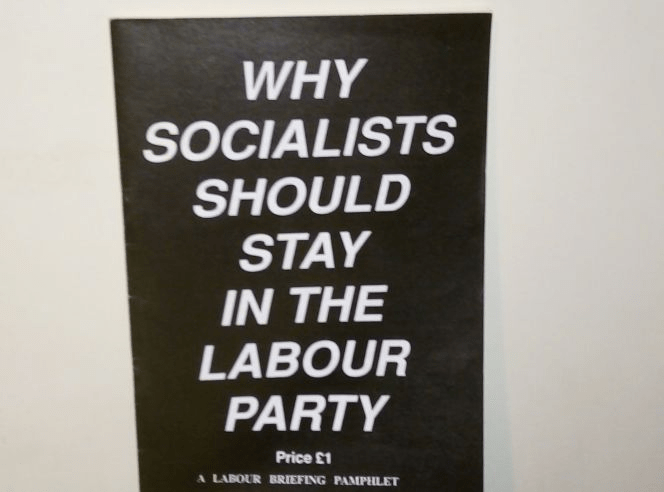

Labour Hub has published a number of articles recently about the Labour Briefing tradition of non-sectarian, pluralist debate and organic work in the mass organisations of the working class. Thirty years ago, Labour Briefing published a pamphlet, Why Socialists Should Stay in the Labour Party, and I was curious to see if the arguments it presented then are still valid today.

There is a striking similarity between then and today’s circumstances. Labour in 1992 were about to go into a general election which they were really expected to win. After thirteen years of Conservative government, the ruling party was in turmoil. Margaret Thatcher had been deposed due to a combination of her increasingly authoritarian style, her strident anti-Europeanism and, above all, the failure of her signature policy, the Poll Tax, overthrown by mass action by millions of working class people. The Tories had replaced her with the weak, uncharismatic John Major, who presided over a deeply divided party, with neither mandate nor coherent policy agenda.

Neil Kinnock, leader of the Labour Party for nine years, should have been wiping the floor with the Tories. But his tight control over Labour’s organisation belied a deeper malaise. As the late Mike Marqusee observed in his Introduction:

“The Labour Party enters the general election campaign of 1992 in poor shape. The rightward shifts in policy have disarmed it before what remains a hugely unpopular Tory government. The centralisation of authority and the purge of left-wingers has undermined its always fragile activist base.”

Sounds familiar?

The pamphlet draws on a diverse range of contributors and the key arguments for socialists staying in the Labour Party are repeatedly expressed. Above all, there is the structural link between Labour and the trade unions. “Do those who wish to depart the Party also advocate a rupture of this link?” asks Mike. Then as now, most would answer no.

But unlike today, this was written at a time when the trade union bureaucracy was firmly on the right and supporting the Kinnock leadership in marginalising the left. The post-miners’ strike ‘New Realism’ policy advocated by most union leaderships of caving in before Tory anti-union laws was essentially the same as Neil Kinnock’s ‘dented shield’ approach to how Labour councils should operate. “To abandon the political sphere of struggle and deal only with its trade union manifestation will not get to the root of the problem,” wrote this author thirty years ago.

More broadly, the working class as a whole looks to Labour to represent it and expects the Party to act in its interests. “It does not do so because it is composed of millions of deluded fools,” writes Mike Marqusee, “but out of a genuine, if often contradictory, class consciousness.”

Since the Party Conference in September 2022, an estimated 20,000 new members have joined Labour’s ranks. Far from being committed supporters of Keir Starmer – or any particular faction – this is an indication of how people look to Labour to lead the fight against the Tories and fix the problems they face in their daily lives. It is, as Kevin Flack points out here,

“a broad church… It has swung from left to right and back again, and to leave at a time of rightward control is to negate the work of all those who stayed and fought in the past and often won significant gains at times of heightened class struggle and awareness.”

The role of socialists in the Party is to help those supporters hold to account the MPs who have been elected with their votes and hard work. And in the event of a Labour victory? Kevin Flack’s verdict in 1992 could apply equally to Starmer today: “It will be the shortest honeymoon on record when Kinnock fails to deliver an improvement in living standards and the welfare state – as fail he will.”

This raises the central question of what the Party is. It’s clearly not socialist, but it probably has more socialists in it than any other organisation in the UK. The degree to which it can be radicalised and made to express the deepest interests of the working class is a question less of speculation than of practical action.

The late Terry Liddle writes here: “The Labour Party isn’t its leaders… The Labour Party is the thousands of rank and file members and activists who despite all the leadership’s betrayals remain loyal to the Party and who still retain an instinctive, if not fully thought out and theoretical, faith in a socialist future. It is they who carry out the campaigns and the fund-raising, who vote against witch-hunts and expulsions and for socialist policies… To abandon these activists who constitute a potential mass base for socialism in Britain, would be criminal.”

The job of socialists in the Party then is to help focus and express this process. As Dorothy Macedo says in a piece entitled “Let’s not expel ourselves!”:

“We have to show that we are serious about the actual struggles taking place, such as over the Poll Tax, hospital opt outs and racism, that concern large numbers of people. We have to build links between such campaigns and local Labour Parties and unions wherever possible. This will make a much greater impact in developing socialist consciousness and support for socialist ideas than perfect programmes and propaganda from a distance.”

It is ironic that Labour Party activists have to explain this point to self-styled Marxist grouplets, as Marx himself encapsulated the idea when he wrote, “Every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programmes.”

“Propaganda from a distance” looks even more distant during an election campaign. The disdain by some on the left for ‘electoralism’ is an act of self-harm, if it means sitting out the single most mass political participation activity there is. As Mike Marqusee says here:

“Abstract calls for a Labour vote are not a sufficient response to this reality. Playing an active part in the electoral battle means fighting within the Labour Party over the content of manifestos, the selection of candidates, the strategy and tactics for elections.”

The easiest argument in favour of socialists staying in the Labour Party is to survey the quality of the so-called alternatives. As Mike Marqusee puts it:

“The chimera of an ’independent’ socialist party, to the left of Labour but somehow different from the democratic centralist sects, is resurrected every few years only to die an obscure death after a few more. Without a mass base in the working class, which in this society can only mean a base in the organised workforce, such an ’independent’ left party can only be a propaganda party – a talking shop which, in the absence of the discipline imposed by a mass base, will rapidly be torn apart by sectarianism, egotism and triviality.”

These words ring even truer after the experiences of left ‘alternatives’ in recent years.

But there’s a possibly worse alternative: leaving the Labour Party… to do nothing. As Kevin Flack notes here:

“I have seen many good comrades leave the Party, most to drift off into inactivity. It’s one of the most depressing sights in politics today.”

In 1992, he did not rule out for all time a split from the Labour Party. “But if that break is to be meaningful and successful, then we must act collectively and not as individuals, pissed off when the going gets tough. After all, if we believed in individual action we wouldn’t have joined the Labour Party in the first place.”

In the last couple of years, over 150,000 members have quit the Party, many of them former Corbyn supporters. It’s understandable: their contribution has been disparaged under the Party’s new leadership and they have had enough of being ignored, manipulated and mistreated. But as I have emphasised before, while not criticising individuals who take this route, withdrawal does not constitute a strategy.

But socialists in the Party cannot just shrug their shoulders at this exodus. Some serious thinking is necessary about how these comrades can be organised with so they are not lost to political activity in their entirety. There may be no electoral alternative to Labour, but a pluralist movement should be broad enough to accommodate a much wider layer of activists than those who see the need to work within the Labour Party.

Going back to where we began, Kinnock’s Labour Party never did win the 1992 general election. The Tories were returned with their highest ever vote and Kinnock quit the leadership son afterwards, his dubious achievement having been the longest-serving leader of the Opposition of the century. Mike Marqusee’s words about Kinnock’s purge of left-wingers undermining Labour’s fragile activist base were highly prescient.

Today Keir Starmer is widely expected to win the next general election but the Party he leads is in a similarly bruised state, with activists demoralised at his leadership’s blatant factionalism and fixing of selection contests. It’s over two years to when the next election must be held and Rishi Sunak may prove to be a far more astute Tory leader than John Major. Starmer will need to think carefully about repairing his fractured Party if he really wants the keys to Number Ten.

As for socialists in the Party, the big difference from 1992 is the upsurge in industrial action and the emergence of more combative union leaderships. This will find a reflection inside the Party, whether Starmer wants it or not. For grassroots activists there is a lot to play for.

Mike Phipps’ new book Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: The Labour Party after Jeremy Corbyn (OR Books, 2022) can be ordered here.

[…] thirty years ago, Mike Marqusee identified the central difficulty facing all such formations in the UK context: “The chimera of […]

[…] Phipps notes, “Over thirty years ago, Mike Marqusee identified the central difficulty facing all such formations in the UK context: “The chimera of […]