Mike Phipps reviews Transforming Brent Libraries, by James Powney, published by AuthorHouse, and sets the record straight on an important local struggle

Some years ago I was involved in a small way in the campaign to prevent the closure of a local library. Frustrated at the fact that the Chair of my Constituency Labour Party repeatedly and on specious grounds kept ruling out of order my branch’s motion opposing the Council’s cuts to local libraries – the CLP Chair was himself a Councillor, never a good idea – I gave an interview to the local paper.

I said there was real anger about the library closures and it was proving to be the most toxic issue for the Party locally since the war in Iraq. I added: “I think it is inevitable that James Powney will be held personally responsible for the way he has handled these closures.”

Naming this local Councillor, the lead member responsible for the closures, was not mischief-making on my part. It was intended to protect the local Party from a wrong, vote-losing policy, which was allowing local Lib Dem activists to grandstand over the issue – the same party in government that was cutting local authority grants which put councils in such a desperate financial plight. “The tragedy would be that the Liberal Democrats would benefit when it is their government pushing through these cuts,” I pointed out.

It must have been a quiet week in Brent, which is in northwest London, because the interview was put on the front page. It elicited a phone call from the Chair of the CLP, who had never contacted me before (or since), saying how much he admired all the work I did for the Party, etc., etc., but couldn’t I just drop this issue and move on?

That would have been difficult. The whole library closure programme felt like a great injustice locally, given that 82 per cent of residents who took part in the consultation said they didn’t want the libraries to close. In the interview, I said: “I don’t think the consultation was undertaken seriously and I don’t think that the process whereby local groups were invited to put their ideas forward to rescue the library was taken seriously either.”

The contempt with which campaigners’ alternative proposals were met by Councillors responsible now seems undeniable from the latest evidence – an account by the key perpetrator of the closure programme.

I didn’t know James Powney had written a book about all this until I saw a letter he wrote to the Guardian last December publicising it. Transforming Brent Libraries is mercifully short at 71 pages, and self-published, for good reason. It would be hard to see this making the best-seller list.

As Lead Member for Environment and Neighbourhood Services in the London Borough of Brent, Powney “oversaw the successful transformation of Brent Library service in raising both the total number of loans and visitors to become one of the most successful public library services in the UK,” trumpets the opening line of his biographical note.

But this doesn’t tell the full story. He also presided over the closure of half of the Borough’s libraries. The scale of protests – meetings, demonstrations, media activity, celebrity involvement – within and beyond Brent was immense. Powney later refers to protesters as a “baying mob”.

He claims the campaign was “principally led by a small number of single issue campaigners, many of whom were not from the area.” But the anger against the closures was very local and was reflected inside the local Labour Party where Powney was a Councillor.

One of the most contested closures was that of Kensal Rise library, originally opened by Mark Twain over a century earlier. It was located in Kensal Green ward where I was Chair of the local Labour Party branch and which Powney represented as a Councillor. Meetings were poorly attended until the closures were announced. Then angry members began to turn up in droves. At the earliest opportunity, Party members voted to deselect him as their Council candidate.

In the Acknowledgements, Powney writes: “In writing this book, I should acknowledge some debts, possibly including the Friends of Kensal Rise Library (FKRL) who through sheer determination and litigiousness stretched the whole saga out to make enough material for a book.” This mocking, supercilious tone towards campaigners, invariably disparaged as “litigants”, becomes increasingly wearing as the book drags on. The unfortunate Powney finds he has do a lot of ‘explaining’ of how things work to the ignorant activists, a “continuous barrage” of whom had the cheek to turn up to his Councillor surgeries.

Equally ignorant, in this version of events, were the celebrities that campaigners sought to “drag in” to promote their cause. They are treated with some contempt here – apparently, celebrities care about libraries only because they remind them of their childhood.

Creative ideas to take over the running of libraries that the Council was seeking to shed from its remit are dismissed as the interference of a “lumpenproletariat”, hopelessly tainted by association with Cameronian notions of a “Big Society”.

At the end of this tedious rant, Powney attempts to draw some lessons from the whole sorry experience. The main one seem to be: what a pain pressure groups are, and how unscrupulously they are prepared to exploit their celebrity backing to “magnify the noise made without any interest in truthfulness.”

But happily, “After the decision is done, those who opposed it are surprisingly forgetful of the position they took.” That can’t be right – if it were, Powney would not have been deselected as a Kensal Green Councillor by his own Party.

It would be unfair to blames James Powney solely for this debacle. As he rightly says, all members of the Council Executive voted the libraries project though unanimously, despite what he concedes was a “massive petition” in opposition.

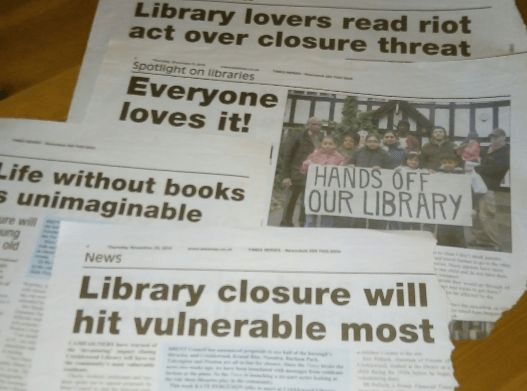

Arguably the campaign against library closures and the publicity it generated contributed to the ousting of the then leader of Brent Council in May 2012. By then the issue had been in the local newspaper virtually every week for eighteen months, taking up quite a few front pages, as on November 18th 2010, when the Willesden and Brent Times opened, under a banner headline “IT’S OUTRAGEOUS” with “Council chiefs spent more than £600,000 on refurbishing two libraries – just months before announcing plans to close them.”

Other headlines included “Library lovers read riot act over closure threat” (December 16th 2010), “Rallying cry to save our libraries” (January 17th 2011), “Read-in spreads word about library battle” (February 10th 2011), “Library campaign groups are united” (February 17th 2011), “Vote to axe libraries ‘a stab in the back’” (March 3rd 2011), “Legal threat from library campaign” (March 10th 2011), “Final battle for libraries” (March 17th 2011), and so on.

So my own front-page splash in April 2011 was not out of the ordinary. Far more shocking was the report about Kensal Rise Library a year later, headlined “Library stripped of books in 2am raid by council”. The report ran: “Most campaigners were asleep when council officers, flanked by a dozen police officers and security staff, swooped on the building at 2am and began emptying it of books, murals and even a commemorative plaque celebrating its opening in 1900 by American author Mark Twain.” Campaigners saw this for what it was: an act of vandalism.

James Powney obviously feels that the damage to community relations was a price worth paying on the road to ‘transforming’ Brent’s libraries. But even his own claims about overall increased library usage are questionable: a local new report in 2012 cited a Freedom of Information request showing that in the five months since the library closures, there had been a 20% drop in library visits.

The wrong-headedness of the whole scheme is underlined by the fact that two of the buildings legally had to be handed back to All Souls College, Oxford, the original owners, once they stopped being used as libraries. Thus the Council lost forever valuable assets.

It was thanks to the tenacity of campaigners that the case for a local public library in Kensal Rise continued to be made with the developer for some time after Brent Council surrendered the property, with the result that the new development had some space set aside for a modest community library and meeting space. It was a small victory and testament to the commitment of the campaigning residents and service users of whom Powney is so disdainful.

Some local Party members were far more involved in this effort that I was. I should particularly mention Claudia Hector, who was also a local Councillor in the ward and worked tirelessly with the campaigners for a positive outcome and whom Party members went on to select for two further terms of office.

Mike Phipps’ new book Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: The Labour Party after Jeremy Corbyn (OR Books, 2022) can be ordered here.

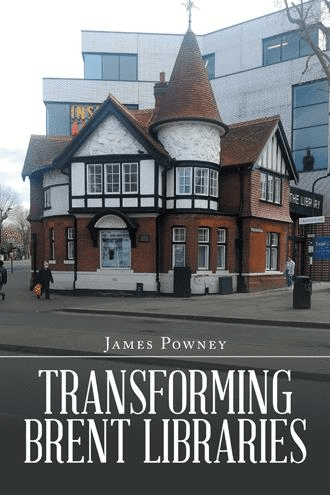

Main image: Kensal Rise Pop Up Library, opened by community activists after Brent Council closed its library on the site, c/o author.