By Isabelle Merminod and Tim Baster

How do you build resilience in war, particularly if there is large scale internal movement? There are about 6 million ‘internally displaced’ Ukrainians who have been forced from their homes by the Russian army. They have usually lost their jobs. They have often been torn away from their pre-war networks of friends and families.

Waiting for Godot, King Lear and A Christmas Carol, in Ukrainian

Some Ukrainians are using the theatre and performance techniques to survive psychologically and also to develop personally:

Samuel Becket’s Waiting for Godot, an abridged King Lear, both in Ukrainian, and both played in an old and beautiful synagogue building (with a terrible history) in Uzhgorod on the western Ukrainian border with Slovakia.

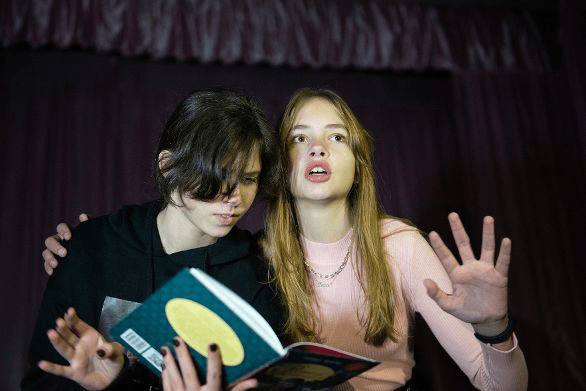

Scene in King Lear. Uzhgorod

A theatre company, mostly children, in the ruins of Bucha rehearsing Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol to the light of mobile phones, due to power cuts.

Displaced actors from other areas of Ukraine, already part of a pre-war network of ‘theatres of improvisation’, working with the displaced in the west of Ukraine. A network of clowns which manages to continue, despite everything.

Hatred and the capacity for love

For Viyaheslave ‘Slava’ Yehorov, who heads the Theatre of the Displaced Uzhik in Uzhgorod, the reason for creating a theatre of the displaced is not merely cultural. It is also to maintain the Ukrainian people’s capacity for love, in opposition to the raging hatred continuously fuelled by this conflict. King Lear is about love: “We don’t find love in the world, we only think of war. The people can be destroyed if they do not have love in their hearts… Without love there will be collapse.”

Slava says he choose Waiting for Godot because, “For me it is about broken communication with people. People are very close but with no communication, and this is an absurd situation….but this absurd situation with no communication is [now] normal in real time.”

The absurd lack of communication in Waiting for Godot is mirrored by the bloody lack of communication between Russia and Ukraine. It has become normalised. Slava develops this similarity by pointing out that the Russian and Ukrainian roles have become reversed, as in the play. The Ukraine of today was the geographical area called “Rus” in old maps. Ukraine was, in fact, the ‘mother country’ – not Russia.

Fleeing from the Russians

Speaking to some of the actors, the stories stream out about fleeing from the Russian army at the beginning of the war. The stories are often similar.

They were living near Kharkiv or maybe Bakhmut or Dnipro. Russian troops are suddenly everywhere. There is no medicine, no food. They wait at the station with thousands of people; there are three trains for Lviv, Uzhgorod or Kyiv. Families choose quickly, they make the decision on the spot and take the train. Their previous life is abandoned in minutes. Then they arrive and stay in temporary accommodation – a school gym, a restaurant, a hall. There is lack of privacy. They suffer boredom and sometimes depression.

Julia Chuguev plays Cordelia in King Lear; she says of the theatre that: “It is very interesting. It is something not ordinary… It is the opportunity to joke, to speak, something to discuss. In the gym [a school gym converted to a dormitory for internally displaced people] it was not possible to communicate with people… I was exhausted by things and it was very difficult. But the theatre helped me to be happy.”

Charles Dickens’ Scrooge in the ruins of Bucha

Oksana Groza heads the theatre company Romeo and Juliet, for women and children. We met her in November 2022 rehearsing for the winter performance A Christmas Carol. For her, the theatre works, “because this is culture and this is because it is something that can distract from the horror.”

Rehearsal for A Christmas Carol. Bucha

She pauses and adds, “It is not only to distract from the horror. Theatre helps people because they can show emotion and do something emotional.” The physical and psychological techniques employed in acting can help the children and women who are rehearsing plays.

She runs her theatre group in Bucha now – her premises in Irpin were badly damaged. Both towns suffered terribly during the early part of the invasion. But after the Russians retreated the children were ringing her to ask that she restart the theatre.

Personal experiences of the invasion

But Oksana, like others working with adults and children in the theatre accepts there are limits; she avoids talking about personal experiences of war. “It is difficult to talk about the war. I see the pain in their eyes.” Her local students and those displaced from other areas may have seen huge destruction or worse.

Improvisation theatre show. Uzhgorod

Anna Pohorielova who ran improvisation theatre classes for children over the summer said that the children she teaches do not have the resources for such painful stories and “it is not the time nor the place to deepen these stories.”

This is a very brief sketch of one method – out of many – used to build resilience in the face of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Improvisation theatre exercises with children. Uzhgorod

This article and photographs come from three visits to Ukraine in March, May, October/November 2022. Isabelle Merminod is a freelance photojournalist and Tim Baster is a freelance journalist.

Main image: Rehearsal for A Christmas Carol. Bucha