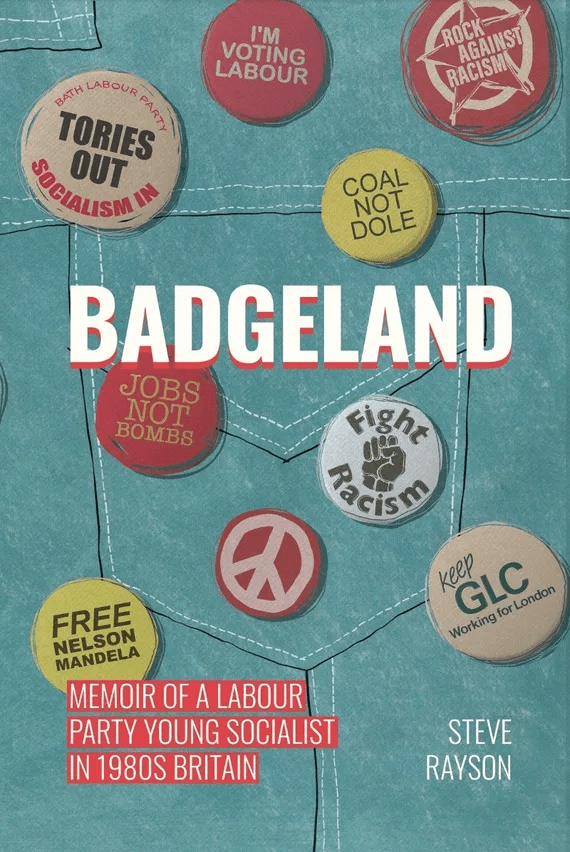

Mike Phipps reviews Badgeland: Memoir of a Labour Party Young Socialist in 1980s Britain, by Steve Rayson, published by Bavant

Steve Rayson, now a grandfather, was a member of the Badgeland tribes of the 1980s. “We wore the CND peace symbol and badges that read: ‘Coal not Dole’, ‘Nuclear Power, No Thanks’, ‘Rock Against Racism’, ‘Jobs not Bombs’, ‘Tories Out’, ‘Free Nelson Mandela’, ‘Tony Benn for Deputy’, and ‘Keep GLC working for London’. Our chests demonstrated our opposition to poverty, nuclear weapons, fascists and apartheid.”

Steve grew up on an estate in Swindon and went to a school that prepared most of its pupils for a life in the town’s factories – Pressed Steel, where many of the workforce ended up with severe hearing loss due to the constant noise, or the rail works where workers, like the author’s father, were exposed to asbestos and later developed cancer.

Steve stayed on at school to do A levels. Hearing someone use the word “socialist”, he looked it up in the Children’s Encyclopaedia Britannica and decided he agreed with the idea. When a girl in his class said she had joined the Labour Party Young Socialists, he looked up “the Labour Party” too, before joining himself.

Here his ‘political education’ begins, with a leading Militant supporter, appropriately nicknamed Trotsky, giving him a copy of Lenin’s The State and Revolution to read. The only problem is that his working class mates – or at least his father’s – prefer discussing football to politics.

Steve passes his A levels and goes to Bath University. He’s not only the first in his family to go to university – he’s never even met a student before!

Of course, it’s another world. When he returns after the first term, he is aware of a new distance between himself and his family. His brother accuses him “of being ‘up myself’. He was right. I was frustrated we had cheap instant coffee, sliced white bread, watched sitcoms and had The Sun delivered.”

Rayson’s narrative takes us through the key events of Thatcherite 1980s – the IRA hunger strikes, Tony Benn’s campaign for the deputy leadership of the Labour Party, the massive rallies for nuclear disarmament, the Falklands War, the miners’ strike and Thatcher’s attacks on local government.

But while he underlines how mistaken he was to expect the Tories to be turfed out by a left-led Labour Party in 1983 and is self-critical of his and his Militant comrades’ tendency to lecture people dogmatically about socialist politics, he is rather on the fence on the big battles of the period. Was he right to take the stand he did – on equalities, for example – even if many in the working class he was talking to – or at – were not interested in his arguments at the time?

Graduating from Bath, Steve moves to London to a post on the Greater London Council’s graduate recruitment scheme. Despite the new leadership of the left wing Ken Livingstone, the organisation was far from exemplary, with only 35 women out of the 550 managers. The Staff Association was primarily concerned with maintaining its privileges in relation to the GLC’s manual workers.

Rayson skilfully interweaves the equalities battles of the era with the rise of a more liberal consumer culture, which his younger self is increasingly drawn into. He contrasts the slick PR campaign mounted by the GLC against its impending abolition by the Thatcher government with the poor media image of miners’ strike leader Arthur Scargill and notes that both struggles got little support from the Labour leadership of Neil Kinnock.

Otherwise, the year-long strike – the defining industrial battle of the entire era – is strangely absent from his life, which seems odd for someone so drawn to political activity from an early age. In the summer of 1984, he goes on a march in London in support of the miners – “an uneasy coalition of working-class miners and middle-class London liberals” – but is unenthusiastic about the strike. He’s even drawn to the Labour leadership’s conciliatory line, worrying about the absence of a national strike ballot and entirely missing the potential of the dockers’ strike that summer to transform the situation.

I really enjoyed the youthful if naïve enthusiasm for radical change captured at the start of this book. But as Steve grows older in a gentrifying suburb of London, he seems to lose his grounding and for him the working class increasingly becomes his dad’s ageing and not especially progressive drinking companions and Swindon Town Football Club. Even his musical tastes become more conservative.

The 1980s witnessed defeat after defeat – the miners, rate-capping, the abolition of the GLC, the Wapping print strike, two general election defeats for Labour – alongside a longer term rise in deindustrialisation and urban deprivation. The lessons Rayson draws from this are that Thatcher won the war of ideology and that the radical left with whom he once campaigned were deluded.

But it’s not that simple. Some of Thatcher’s supposed ideology – meritocracy, entrepreneurialism – was not uniquely Thatcherite; and her social conservatism was invariably divisive. Maybe his dad’s mates didn’t have much time for women’s or LGBT rights, but so what? Over the next few years, there would be a sea-change in attitudes on such issues.

More importantly, it’s not always helpful to see electoral politics in terms of hegemonic ideologies. The Tory vote among working class people at this time was more pragmatic, based on potential gains to be made from the Right to Buy policy and a cost-benefit analysis of whether the electoral offer being made by Neil Kinnock’s Labour would actually be of much help to them. Many voters may yet draw a similar conclusion about today’s Labour Party at a future general election. But it would be wrong to conclude that they had bought into the Tories’ political ideology, such as it is.

But by the late 1980s, that is exactly what leading Labour figures did. Thatcher’s success meant socialism was dead. Elections could be won only from the centre. New Labour was born – what Thatcher called her greatest achievement.

Rayson’s book ends, with Steve joining the ranks of entrepreneurs, before the events of Thatcher’s last term that finally punctured her popularity – her attacks on the public sector, especially the NHS, and her much-loathed Poll Tax. Nor does it chart the long-term shift in public opinion away from some of her values, so that when New Labour was finally elected in 1997, it was on policies that were often to the right of public opinion – including on tax and social ownership.

However electorally appealing – and of course her declining support was masked by a first-past-the post electoral system – the Thatcher governments did huge long-term damage to Britain. We and the author can take some comfort from the fact that he was on the right side of all the major battles of that era, even if they ended in defeat.

Mike Phipps’ new book Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: The Labour Party after Jeremy Corbyn (OR Books, 2022) can be ordered here.