Caribbean Labour Solidarity are launching a special issue of the journal Socialist History on Sunday 4th June. Here they provide a preview – more details below.

The history of socialism in the Caribbean is intimately connected with the emergence of the organised modern working-class movement in the region, and so is essentially a phenomenon with origins in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. As C.L.R. James, in his introduction to Ron Ramdin’s 1982 history of the working class movement in Trinidad, noted:

“We now come to the period when the Caribbean people, on the whole, began to model what they need, particularly the working class, on the great discoveries and achievements of the working class abroad. What the Trinidad working class is demanding is not in its past history. But it has reached a stage where what has taken place abroad (and the development of the working class abroad) has afforded the great advantage in that the working class in Trinidad which wishes to transform itself is able to undertake what has taken the British, and others, two or three hundred years to learn.”

What was true of Trinidad was true across the Caribbean, and so almost as soon as an organised working-class movement developed so did socialist ideas begin to circulate, something that took much longer to happen in Britain.

In Britain too there was also some ‘Negro socialism’ by 1905. The black Trinidadian Pan-Africanist Henry Sylvester Williams, organiser of the first Pan-African conference in London in 1900, joined the Fabian Society in 1905, having met Fabian socialists Sidney and Beatrice Webb and George Bernard Shaw. He also knew Keir Hardie, leader of the new Labour Party after 1906. In November 1906, Williams, a member of the National Liberal Party, had been elected for the Progressive Party in the St Marylebone Borough elections, explaining that his “object would be to serve the working classes”.

The emerging Labour Party in Britain – which was committed to the maintenance of the British Empire –would shape the relationship between the British socialist movement and socialism in the Caribbean in the early twentieth century, popularising to some limited extent the ideals of Fabian socialism. In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917, a minority of black colonial subjects began to find inspiration in the ideas of Marxism and Communism which challenged the ‘imperial labourism’ and problems of nationalist ‘whiteness’ that beset and bedevilled the British labour movement – even its left wing – at this time (and for a long time afterwards).

The one-time Fabian socialist, the black Jamaican poet and writer Claude McKay, was one such radical, who came around the British far left in 1919. On 31st January 1920, the Workers’ Dreadnought, edited by Sylvia Pankhurst, carried McKay’s article ‘Socialism and the Negro’ on its front page, and McKay’s eloquent anti-imperialist argument is worth quoting at some length.

“Some English Communists have remarked to me that they have no real sympathy for the Irish and Indian movement, because it is nationalistic. But today the British Empire is the greatest obstacle to International Socialism, and any of its subjugated parts succeeding in breaking away from it would be helping the cause of World Communism. In these pregnant times no people who are strong enough to throw off an imperial yoke will tamely submit to a system of local capitalism. The breaking up of the British Empire must either begin at home or abroad: the sooner the strong blow is struck the better it will be for all Communists. Hence the English revolutionary workers should not be unduly concerned over the manner in which the attack should begin. Unless, like some British intellectuals, they are enamoured of the idea of a Socialist (?) British Empire!”

It was not really until the 1930s, as Theo Williams shows in his new study, Making the Revolution Global: Black Radicalism and the British Socialist Movement before Decolonisation (2022), that anti-colonialism really became a current among a significant number of British socialists. The 1930s also saw the Anglophone Caribbean itself erupt with a wave of strikes and labour rebellions, class struggles that opened the road to independence in the post-war period.

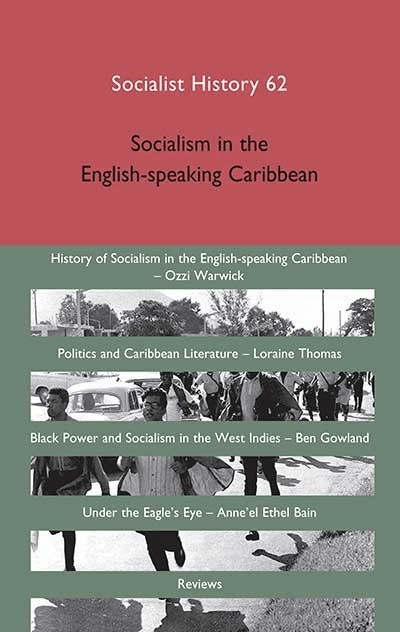

The special issue of Socialist History (Volume 2022 Issue 62) Socialism in the English-speaking Caribbean arose out of a series of online seminars organised by the Socialist History Society, the Institute of Commonwealth Studies and the Society for Caribbean Studies in March 2022.

Ozzi Warwick, himself a leading trade unionist in Trinidad and Tobago, opens the volume with his rich historical overview of socialism in the Caribbean as a current within the wider anti-colonial movement and then challenging neo-colonial domination in the post-war period. He draws our attention to the complexities involved in the formation of these societies and the many challenges both historical and contemporary, confronting struggles for a just social order against the “aggressive neoliberal present”, and locating the key activists and movements well, in their national and regional contexts.

Loraine Thomas in her essay explores the literature of St Vincent and the Grenadines during the era of independence, showing how the radicalism of the 1960s impacted here on the little magazines and journals. This is a uniquely interesting piece, dealing with a subject not often in the spotlight of many ‘on the left’ – literature! Here Loraine has shown in detail, the importance of this genre in raising consciousness and the continuous impact such activism has had. It is all the more important in reflecting what media meant in times different from today’s mediascape.

Ben Gowland examines the politics of Black Power in the Caribbean in more depth, noting what made this current of Black Power distinctive, owing to the influence of, among other things, Rastafarian cosmology, Garveyism and earlier histories of slave revolt. He examines in detail the rise in racial consciousness and the progressive turn into the political economy of the region in relation to past and present imperialist order. Ben also skilfully shows the tensions between cultural awareness and the move to more class-based Party politics. Within the narrative, the role of Dr Walter Rodney is so important here, at a time when his politics is the subject of a number of new publications.

Finally, Anne’el Ethel Bain reminds us that with decolonisation during the Cold War, the Caribbean became an American sea, and the neo-colonialism of the United States forced the left-wing leaderships of Cuba, Grenada and Nicaragua from 1979 onwards to work more closely together for state survival. The challenges in trying to carve out, at the level of state policy, an alternative path to that of imperialism’s historical legacies, in the face of its current global hegemony, is plainly set out here, demonstrating the guile and co-operation engendered by a common experience of US hostility. Such stories are not part of mainstream consciousness relating to inter-Caribbean co-operation during the Cold War; thus Anne’el’s research at this time is vital to fill this gap.

Socialist History Volume 2022 Issue 62 ISSN 0969-4331, Socialism in the English-speaking Caribbean is edited by Christian Høgsbjerg, Michael Mahadeo and Francis King.

Caribbean Labour Solidarity are launching the special issue of the journal Socialist History.

Sunday 4th June 2023 at 2pm Speakers Ozzi Warwick and Ben Gowland

Free to attend, but you will need to register in advance.

Also Live Streamed on YouTube: