Last month, Labour issued a detailed draft policy programme that could form the basis of its next general election manifesto. Allyson Pollock explores the background to the evolution of Labour’s health policy and details what’s missing from the its draft manifesto.

The UK’s winter of discontent is far from over. With inflation soaring to its highest level for 40 years, and with the largest fall in living standards since the 1950s forecast for the coming year, workers in postal services, railways, border control, universities and schools, along with nurses and ambulance staff have been taking to the picket lines since November.

In early January, the BMA balloted its junior doctors for strike action. In May this year, it began to ballot its senior doctors – clinical consultants. In a recent poll over a third of junior doctors are considering leaving the NHS – many, including consultants, have moved over to the private sector. More worryingly clinicians have told us of proposals to change NHS job plans for doctors to facilitate their move into the private sector, that is, working in the private sector but paid for by the NHS and being given incentive payments on top.

Waiting lists are high but those who can’t get care because services have been cut or are no longer available are not included. Several thousand people have died in the last year because of overwhelmed ambulance and emergency services, with many ambulance services and hospitals declaring a critical status.

Public satisfaction with the NHS is at its lowest since 1997. Although private insurance coverage has fallen, there has been a 35% increase in people choosing to self-fund care since 2019, with “market-beating growth” reported in the self-pay market since the Covid pandemic.

Yet at the same time, the public still overwhelmingly supports the NHS’s founding principles, a comprehensive service for everybody freely available at the point of need without ability to pay.

The problem – a two-tier system, with US similarities

‘The NHS at breaking point’ has been a media headline for years. But this time it is different. The truth is far graver. What now exists, especially in England, is a two-tier service which increasingly resembles US health care. There is a blurring of public and private provision and funding: large corporations and equity investors have now well and truly penetrated every part of the NHS and the problem of privatisation within is growing.

There has always been a two-tier system in the UK, where those who can afford to pay, or who have medical insurance, can go privately. But after more than 30 years of reducing public capacity, increasing marketization and promoting private health care, the system has now become embedded within the NHS, facilitated by consultants, nurses, and private GPs, many of whom are now moonlighting or working actively to support the NHS and some of whom have created companies to take advantage of the lucrative contracts that are being awarded.

There are three aspects to this: reduced capacity which is not rebuilt but shoring up the private sector instead; beds in NHS hospitals being available to private companies and private patients; and more private patient units in NHS FTs – facilitated by medics.

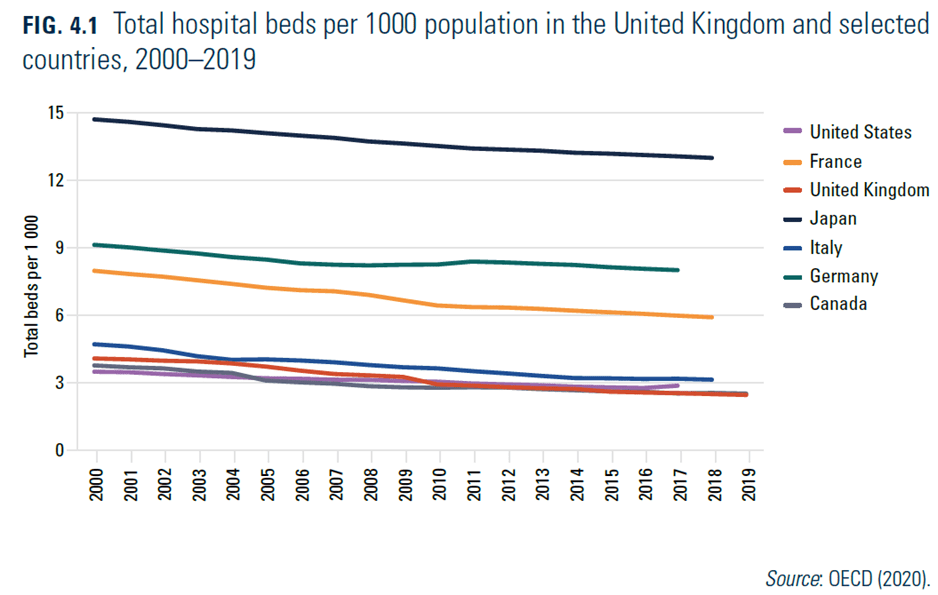

Reduced NHS capacity was seen starkly when the pandemic hit. The NHS didn’t have enough hospital beds. The UK had one of the lowest per capita bed numbers amongst comparable countries, as their number had more than halved from 299,000 in 1987-88 to 141,000 in 2019-2020. Critical bed shortages and lack of facilities and services in the community have resulted in inappropriate admissions of older people to acute beds and delayed discharges from hospitals.

[This Figure is copied and pasted from page 88 of the review of the UK health system which was published in June 2022, accessed from here]

The picture for NHS mental health beds was even worse. They reduced by three-quarters (73%), from 67,100 in 1987-88 to 18,400 in 2018-19. This has led to patients having to travel sometimes hundreds of miles from where they live to private hospitals, or to be treated in acute NHS wards where staff do not have expertise. Since 2015-2016, the number of mental health admissions to NHS acute beds now exceeds the numbers admitted to mental health beds.

The pandemic also exposed the NHS’s low staffing rates compared with similar countries. Critical and persistent understaffing has led to 10-12% workforce vacancy rates, with over 90,000 vacant posts in the NHS and 100,000 in social care in 2021. All this against a backdrop of a declining and ageing workforce, 40% fewer nurses than ten years ago, billions of pounds spent on agency staff and high turn-over.

The government’s panicked response to bed shortages was to create pop-up NHS ‘Nightingale hospitals’ at vast expense, which could not be staffed and were hardly used, and to award 26 contracts to companies running around 190 private hospitals with about 8,000 beds which engage mostly NHS consultants doing private work in their non-NHS time.

Those contracts are estimated to have cost at least £2 billion, but a significant amount of the private capacity was not used. Additional contracts valued at £10 billion were awarded in the summer of 2022 to 52 private companies in order to help reduce waiting lists. NHS England aims for a 20% increase in use of the private sector by March 2023 over 2019-20 levels. The National Audit Office estimates that the average share of elective patients treated privately will increase by only one percentage point to around 9%. But these contracts are a lifeline for private hospitals especially for those whose profits were falling before the pandemic.

Alongside shoring up the private sector, beds in NHS hospitals, especially in and around London, have been made available to private companies via joint ventures, such as HCA Healthcare UK (Hospital Corporation of America), which describes itself as “the largest private health care provider in the world, and the largest provider of privately funded health care in the UK”. As in private hospitals, most of the consultants used to treat private patients in these beds are employed by the NHS.

The two-tier system has also progressed as a result of Parliament having legislated in 2012 to permit NHS foundation trusts to obtain 49% of their income from private patients and other non-NHS sources. There is no obligation on the trusts to reinvest income from private patients in the NHS, only to give information in their annual report on the impact of that income on NHS services, and there are no data which demonstrate that NHS patients have benefitted.

And, again, it is NHS staff who treat the private patients. Tens of thousands of staff are working across public and private sectors on a fee-for-service basis or as employees of private companies or even under the direction of NHS foundation trusts. Moreover, hundreds of medical consultants, mostly employed by NHS foundation trusts and NHS trusts, have equity shares in 34 joint ventures with private hospitals, such as HCA and other private health companies.

NHS dentistry and social care give a taste of what is to come: decreased access, more corporate provision and out of pocket payments. Take ophthalmology where community optometrists are now referring directly from Spec-savers to Newmedica, a company they own, which in turn is billing the new NHS Integrated Care Boards for astronomical amounts. Optometrists are incentivised to refer to the private sector as they are paid a co-management fee and can also charge for fancy lenses and spectacles afterwards. Meanwhile the private sector is busy vertically integrating treatment pathways from referral to treatment. In 2016 the private sector was delivering 11% of NHS-funded cataract procedures in England. By April 2021 it had risen to 46% with only 54% being carried out by NHS trusts.

Meanwhile, across the country NHS eye theatres are being closed and cataract lists are going unfilled. Training has been badly affected as the private sector cherry-picks the easy high-volume, low-complexity cases so that training places are being removed. For example, across the country consultants have told us training places are being removed because they cannot perform the number of cataracts needed to complete their training as the NHS is left with all the complex cases. Meanwhile consultants and theatre staff are migrating across to companies owned by equity investors, some of which the doctors own themselves .

There is no service planning – the private sector is swooping in, cherry-picking the easy conditions and this in turn requires the NHS to reduce its services and make savings. In 2022, nearly 200 NHS consultants wrote to NHSE to warn of “the accelerating shift towards independent sector provision of cataract surgery” which is already having a “destabilising impact” on safe ophthalmology provision, and that wide scale use of private providers will “drain money away from patient care into private pockets as well as poaching staff trained in the NHS.”

The government says it is focusing on clearing waiting lists. But ophthalmology is not just cataracts: it includes complex eye disease, glaucoma, retinal conditions, macular eye disease, cancers, diabetic eye disease and where the risk of blindness in older age with all the attendant problems is high. The incoming president of Royal College of Ophthalmologists Professor Ben Burton warned: “What’s happening is that staff who could be treating preventable but irreversible sight-threatening conditions like glaucoma, macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy are instead doing cataract surgery for private providers.”

These risks are increasing as the NHS eye services shrinks.

The government focus is on ‘choice’ of provider but equality and impact assessment are ignored and there is now growing evidence that as the private sector expands, it substitutes for NHS provision and there is increasing inequality in access, with patients living in richer areas getting priority. But it seems Wes Streeting with his commitment to using ‘spare capacity in the independent sector has bought into the New Labour rhetoric that it doesn’t matter who provides the services so long as it is funded by the NHS. The same is happening in orthopaedics and many other areas.

How has the two-tier system come about?

This two-tier system came about following deliberate government policies dating back to the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher. Few, if any, Tory politicians instinctively like the NHS. In their ideology, it’s an inefficient monopolistic behemoth that denies choice, prevents competition and stifles innovation. But they realise most voters want it, and every model of health care involves public funding – even in the US, government funds most health care, so wholesale privatisation was, and is, a non-starter.

Instead, their approach was to start by introducing market principles and the necessary bureaucracy for pricing and billing. It began with the major closure of NHS long-stay hospitals in the 1980s under the rubric of ‘care in the community’. The reality was a huge expansion in private nursing homes, funded by individuals and local authorities, with some NHS funding. There are now over 400,000 long-stay beds in the independent sector, a five-fold increase since the 1970s.

Next, it was the turn of NHS general and acute and mental illness hospitals. In 1990, hospitals were converted into ‘trusts’, described as ‘providers’, and were required to compete with each other for contracts from NHS health authorities described as ‘purchasers’.

Tony Blair took this approach even further – he was, after all, Thatcher’s “greatest achievement” in her reported view. The policy of the ‘Private Finance Initiative’ (PFI), under the rubric of ‘public–private partnerships’, was rolled out at scale. Instead of government raising the capital, banks, builders, service operators and equity investors created joint ventures to raise the financing and enter into 30-to-60-year contracts with the state to design, build, finance and operate new hospitals and buildings. It paved the way for what in effect became sale-and-lease-back arrangements.

The high costs of debt servicing and equity returns drove the sale and closure of public hospitals and services on an enormous scale over almost three decades. They continue to create affordability problems. Around 12% of hospitals’ annual revenue is now spent on these arrangements, more than the expenditure on medicines in some hospitals, leaving managers with no choice but to quality-shave –that is, reduce skill mix and staff and thus impair quality of care.

In 2003, the Blair government acceded to private sector lobbying to extend the policy to the operation of clinical services, top-slicing funds for contracts under the Independent Sector Treatment Centre programme, and allowing private health care corporations to enter into joint ventures with NHS hospitals and to run and operate GP surgeries. In 2008, the Tory health minister who introduced the 1990 reforms wrote: “In the late 1980s I would have said it is politically impossible to do what we are now doing.” In 2023 Wes Streeting continued to endorse the private sector, stating that he would use it to increase capacity in the NHS.

The 2012 Health and Social Care Act ended the duty of the health minister to provide key health services throughout England. It shifted care away from planning services and the workforce on a geographic basis, introduced virtually compulsory tendering and increased decision-making by market providers.

The 2022 Health and Care Act went further still, leaving only a veneer of a public system but in reality handing control of public expenditure and decision-making to networks of NHS and private providers which resemble US Health Management Organisations in several respects. Higher costs, more waste, lack of access, growing unfairness and poorer outcomes are well-documented effects of marketised two-tier systems.

Does the Labour Party’s draft manifesto reverse this?

What’s missing?

Missing from the draft manifesto is the need for legislation to reverse the growing marketisation and dismantling of the NHS in England. While there is a ‘convenient consensus’ that the NHS needs more money, no one is looking to see where the money (billions of pounds) is going and how it is being spent – not in the NHS.

The cry is no more top-down reorganisations – ignoring the legislative changes that have led to the erosion and rapid dismantling of the NHS and ignoring the fact that only reinstating the duty to provide services will protect the NHS and ensure that Parliament once again has oversight.

The manifesto is silent on the critical shortage of NHS beds and the withering away of services. It does not say it will require the NHS to stop treating private patients and use NHS funds instead to rebuild and increase capacity within the NHS, so the need to ‘go private’ does not arise. It does not say it will require NHS staff to choose between remaining in the NHS or practising in private medicine. It does not say it will rebuild and restore NHS services within the NHS.

Instead it focuses on rebuilding staffing, but does not address either the enormous loans and debts that doctors, nurses, physios, pharmacists, speech and language and occupational therapists and others in training are now incurring. Nor does it address where they will work in future. Current policies further incentivise staff to look for easier ways of making money in the short term and their steady drift and movement across to the private sector is happening at speed.

But just as legislation has allowed the two-tier system to flourish, it is only legislation that can reinstate the NHS as a planned system of universal public health care throughout England. Relying on politicians to do so is not promising. Only public mobilisation on a massive scale such as that organised by Nan Goldin over Oxycontin and Purdue and Sacklers can halt the NHS withering away before our eyes.

Professor Allyson Pollock is a clinical professor in public health at Newcastle University. See more about the NHS Reinstatement Bill here.

Image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/alanshearman001/52256174035. Creator: Alan Shearman. Licence: Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0)