Our energy correspondent analyses the Labour leader’s ‘green mission’ speech in Edinburgh earlier this week

The big change to Labour’s policy had already been signalled ten days before Starmer’s speech. Rachel Reeves announced that plans for a green prosperity fund to start in the first year of a Labour government were being delayed. It would “ramp up” by the middle of a first Labour Parliament.

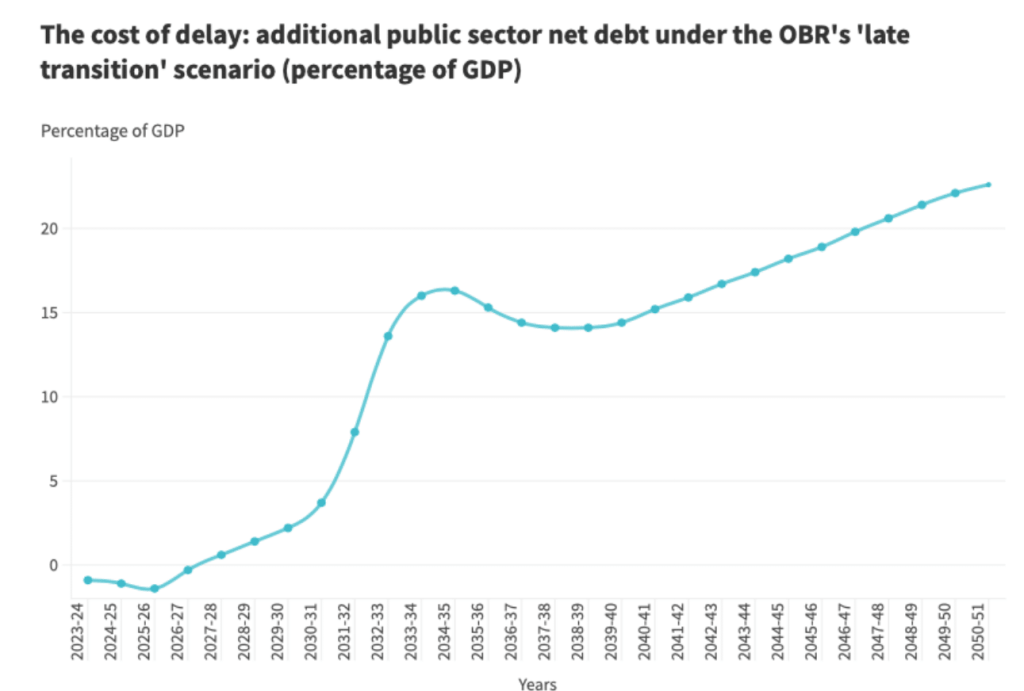

The problem with this is that the longer the investment is left, the costlier it gets. The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that delaying action until after 2030 increases debt to GDP by 23 percentage points over the long-term.

Source: Office for Budget Responsibility. Chart taken from page 4 of Labour’s briefing document ‘Make Britain a Clean Energy Superpower’.

Given that the upward tick in public debt starts in 2025-27, is Labour’s strategy to ramp up to £28bn by as late as 2027 remotely sensible? The delay would lead to additional public debt – despite Labour arguing its policy of delay is based on prioritising fiscal responsibility due to higher borrowing costs.

Warm Homes Plan

Labour pledges to “work with the Scottish Government on our Warm Homes Plan, ensuring that all homes are upgraded to at least EPC C within a decade.”

They also suggest they will upgrade 19 million homes as part of the Warm Homes Plan, which seems unclear as fewer than 19 million homes are below Band C. Uprating homes to Band C, which itself is not a high standard, by as late as 2034 will do little to help those struggling to heat their homes in the 2020s.

Clean Electricity by 2030

“Based on gas futures price projections, our mission has been estimated as saving UK households £93 billion over the rest of this decade. When combined with our Warm Homes plan, this means households would stand to save up to £1,400 per year.”

If green public investment is ramped up to the full £28 bn only from 2027 this poses additional challenges to reaching 100% clean electricity by 2030.

Given the majority of potential savings on energy bills outlined in Labour’s policy briefing comes from meeting its clean electricity target – ending the use of volatile gas in the electricity system – this has implications for the cost of living as well as our net zero pathway.

“To achieve our mission by 2030, a Labour government would:

● Quadruple offshore wind with an ambition of 55 GW by 2030

● Pioneer floating offshore wind, by fast-tracking at least 5 GW of capacity

● More than triple solar power to 50 GW

● More than double our onshore wind capacity to 35 GW

● Get new nuclear projects at Hinkley and Sizewell over the line, extending the lifetime of existing plants, and backing new nuclear including Small Modular Reactors

● Invest in carbon capture and storage, hydrogen, and long-term energy storage to ensure that there is sufficient zero emission back-up power and storage for extended periods without wind or sun, while maintaining a strategic reserve of backup gas power stations to guarantee security of supply

● Double the government’s target on green hydrogen, with 10 GW of production for use particularly in flexible power generation, storage, and industry like green steel.”

This adds up to 155GW of clean electricity by 2030, compared to up to 8GW for GB Energy projects, which involve partnership with councils, co-ops, community groups and “energy companies”. If the above policy commitments are met, this would leave GB Energy generating up to approximately 5% of clean electricity, with at least some of this in partnership with private energy companies. It is unclear whether this would include partnerships with the existing “Big Six” incumbent players.

Comparing GB Energy to international equivalents

The ‘up to 8GW’ figure for GB Energy compares to 15.5GW for Denmark’s Orsted at present, 30GW by 2030 for Norway’s Statkraft, 15GW for Sweden’s Vattenfall by 2030 and 50GW of renewables from EDF in France by 2030. Notably Denmark, Sweden and Norway have much smaller populations than the UK.

When the Great British Energy policy was announced in 2022, Labour made comparisons to EDF and Vattenfall. The Financial Times went as far to suggest the policy was “modelled” on state-owned companies such as EDF, while Sky reported a Labour source as stating that GB Energy would “eventually” be as big as EDF in France.

This difference in scale is significant, with the details so far suggesting GB Energy will only be up to a fraction of the size of comparable publicly owned entities.

Finance

The briefing states “Labour will make the UK the green finance capital of the world, mandating UK-regulated financial institutions – including banks, asset managers, pension funds, and insurers – and FTSE 100 companies to develop and implement credible transition plans that align with the 1.5°C goal of the Paris Agreement across their portfolios.”

This policy commitment, made in 2021, appeared to have been sidelined or dropped. It is a good step from Labour to see the commitment included in its climate mission. Further, it is positive that the policy is to keep global heating within 1.5°C, in line with the IPCC’s objectives, rather than just the UK’s insufficient target of net zero by 2050. If enforced effectively, this would force the UK’s biggest firms, alongside financial sector companies, to decarbonise at a timely pace.

At the same time, Labour’s aim to make the UK a ‘green finance capital’ raises other issues. The financial sector has been shown time and time again to fail at genuinely sustainable investments, including but not limited to renewables. And a green economy in which finance is dominant, will remain one where profit maximisation and speculative investment are at the heart of our economic model.

Electricity prices

Interestingly, the briefing notes “Labour will look at measures to de-link the price of renewables from gas, to ensure their low prices are passed on to households and businesses.” This pricing system is a significant part of the current energy crisis, and this is one option which may help address high prices.

UCL’s Institute for Sustainable Resources explored the implications of ‘splitting’ the electricity market into fossil fuels and clean energy in a recent report. However, this leaves the question of reversing energy privatisation unanswered – despite the massive sums being made by energy shareholders

Four and a half decades of neoliberalism have left the UK’s energy sector vulnerable to external shocks, rife with profiteering by investors and lacking strong public oversight. In this context, the UK has been particularly badly equipped for the transition to renewables and is off-track to meet both UK and Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change climate targets.

Conclusion

Public ownership of energy and greater state intervention as part of a Green New Deal offer a serious and urgently needed route forward – one which Keir Starmer had pledged in his 2020 leadership bid. Yet, despite backing a publicly owned energy company in Great British Energy and plans for a significant roll-out of insulation, Labour looks like it is moving in the opposite direction.

Image: Iberdrola contributes to the economic development of Asturias with investments in renewables and support for industry, local employment and entrepreneurship. https://www.iberdrola.com/press-room/news/detail/iberdrola-contributes-economic-development-asturias-with-investments-renewables-support-industry-local-employment-entrepreneurship. Creator: David de la Iglesia Villar Copyright: David de la Iglesia Villar. CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 DEED Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International