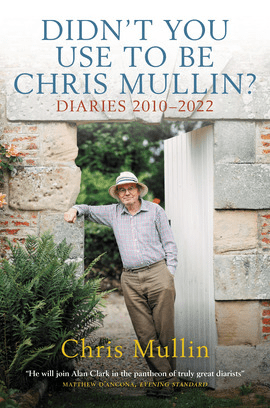

Mike Phipps reviews Didn’t You Use To Be Chris Mullin? Diaries 2010–2022, published by Biteback

Chris Mullin was a journalist in the 1980s whose campaign against the miscarriage of justice perpetrated against the Birmingham Six led to their eventual release from prison – a stand he still gets hate mail about. From 1987 to 2010 he was Labour MP for Sunderland and served as a junior minister in the New Labour governments of the time.

Rooted in the left, he was far too independent-minded to make the transition to loyal Blairite minster and his previous diaries, later made into a play, give a flavour of his original, but often off-message, outlook. In A View from the Foothills, he refers to President George Bush Jr as “an intellectually and morally deficient serial killer.” In Decline and Fall, he reports that Tom Watson lost faith in Tony Blair after Cherie did not like the décor on the No 10 nuclear bunker and had it redone.

Mullin has a tendency to relay chit-chat of this kind but his diaries are also full of astute observations about the civil servants he worked with, the parliamentary whips and the burdens of high office. He is honest about his mistakes, such as calling for an “exemplary defeat” of the firefighters in their 2002 strike. He displays a slightly detached admiration for Tony Blair whom he calls “The Man” throughout his diaries, although this enthusiasm is dented by the war on Iraq, which Mullin opposed.

I was wondering whether Mullin would have much to report since leaving Parliament and becoming a fixture on the book festival circuit. He clearly thinks he does: this new volume runs to over 500 pages. But in the decade after 2010 he inevitably features more as an observer than participant and his observations are not always particularly penetrating.

Whole months go by without anything happening. The Coalition years are dealt with in under 100 pages. Mullin becomes increasingly dissatisfied with Ed Miliband’s leadership, observing that “our economic policy is broadly the same as that of the Tories.” Then Jeremy Corbyn becomes Labour leader and things start to get interesting.

Chris Mullin is no fan of Jeremy Corbyn, viewing him as a man of integrity but entirely unsuited to leading the Labour Party, because as a backbench MP he could endorse numerous worthy causes and never had to say no to anybody. Being in government means making hard choices, which, Mullin suggested in a recent talk, Corbyn would never be able to do. A more serious objection is that it was unwise to have a leader who had so little support among Labour MPs – and who were determined to destabilise his leadership from day one.

That’s his opinion; but what’s missing here is the sense of uplift and hope that accompanied Corbyn’s elevation. The huge influx of members into the Labour Party, making it the largest left wing party in Europe, was one aspect of that. But also notable was the shift in the policy debate, in particular the widespread understanding that Coalition austerity hadn’t worked and was being pursued for ideological reasons and it was now time to try something new. When I raised this with him recently, I got the stock dismissal of Corbyn the man, but no recognition of the transformative effect his leadership had on politics for hundreds of thousands of people.

Nonetheless, he admits that the rise of Corbyn to Labour’s leadership gave his novel A Very British Coupa new lease of life. He also asserts that Corbyn was right to oppose the Cameron government’s plans to bomb Syria in 2015, saying that the Parliamentary Labour Party appeared to be “in the grip of neo-cons”. Elsewhere he refers to Corbyn’s arch-opponents as “headbangers” and is particularly caustic about 2016 leadership challenger Owen Smith:

“Like many a Welsh politician on the make, he lays claim to the mantle of Nye Bevan, although it is far from clear that Nye would be keen on a former drug company lobbyist. He also claims he would have voted against the Iraq War, although he was conveniently not in Parliament at the time and someone has unearthed an interview he gave at the time which seems to suggest the opposite… The man’s a shyster.”

As time wears on, Mullin’s judgement is less shrewd, even succumbing to groupthink. When Theresa May calls an early election in 2017, he is appalled that Labour MPs vote to allow it: “they have walked into a great big trap.” He maintains his pessimism throughout the campaign, but admits that Corbyn is drawing colossal audiences. In the event, Mullin is completely blindsided by Labour’s electoral gains and has little original to say about them.

Despite these weaknesses, there are significant moments of clarity, as in this entry for July 31st 2018:

“The assault on Corbyn for his supposed tolerance of antisemitism is unrelenting. On some days it leads the bulletins. This morning he was having to apologise for appearing on a platform eight years ago with someone who allegedly compared Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians to Nazi treatment of the Jews. It turns out that the individual concerned is a Holocaust survivor, Dr Hajo Meyer, but no matter, he’s the wrong kind of Holocaust survivor. Meanwhile the Corbyn haters in the parliamentary party are scenting blood, openly denouncing him regardless of the damage they are doing to the party and its prospects.”

A month later, Mullin is asked by the Daily Mail if he would go to Venezuela “tomorrow” and write about how far removed it is from being a left-wing utopia. He replies drily, “I am proposing to mow my lawn instead.”

Mullin is justifiably gloomy about Labour’s prospects in the 2019 general election, believing its policies to be undeliverable and its leader unelectable. However, he concedes, “given that so many Labour voters are Brexiteers, any Labour leader would have found the job difficult.”

But he’s also impatient with those in the Party who prioritise undermining Jeremy Corbyn over attacking the Tories. On November 10th 2019, he writes: “David Blunkett, from the comfort of his billet in the House of Lords, complains in the Telegraph about what he calls the thuggery and antisemitism in the Labour Party. Why now, David? And why in the Torygraph? Can’t you just say ‘no’ when they ring up? I do.”

Then Covid strikes, turning Mullin’s world upside down. Few other diarists would write so unsparingly about themselves: “One by one all my pathetic little engagements are falling away. Talks, lectures, literary festivals. Everyone is cancelling. Common sense, I know. I shouldn’t care about it, but I do. Doing things. That’s what I exist for.”

Four weeks later: “If only there was something I could do to help, but as a 72-year-old male with chronic bronchitis and no particular skills, other than the gift of the gab, I am an irrelevance.” After this, diary entries become ever less frequent.

Then on October 30th: “Keir Starmer has withdrawn the whip from Jeremy Corbyn for suggesting, in response to a report from the Equalities Commission, that allegations of antisemitism in the Labour Party have been exaggerated by people with a different agenda. As it happens, I agree with Jeremy… I feel angry about this. Corbyn was never leadership material, but he is a good and decent man and it upsets me to see him cynically thrown to the wolves.”

Mullin even questions whether he still belongs in Starmer’s Labour Party. When he raises concerns about these issues on Twitter, he is the focus of considerable abuse. He calls Starmer’s refusal to readmit Corbyn into the Parliamentary Party “an act of moral cowardice.”

In December 2020, Mullin published a lengthy piece about Jeremy Corbyn and the allegations against him in Middle East Eye, entitled “Labour antisemitism: Why it has become impossible to criticise Israel.” Tory MP Andrew Mitchell told him it was “a superb piece” but others responded with fury.

Yet Mullin’s biggest fear, as his engagements become ever fewer, is that he will no longer be of use: “Running out of ideas. Waking up day after day to an empty diary. What is the point of life except to be useful?”

Beyond these darker thoughts, there is the distinctive Mullin wit. On a visit to the House of Lords: “They have closed their eyes and woken up in heaven.” On Tory minister Lord Frost’s resignation: “The latest of several Brexiteer ministers to flee the scene of their crimes.”

Overall, I was left with the contradictory feeling that the whole book was too long, but I still wanted more. What happens next, Chris?

Mike Phipps’ book Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: The Labour Party after Jeremy Corbyn (OR Books, 2022) can be ordered here.