We reproduce an edited version of a speech made by Dr Peter Purton at the Working Class Movement library, Salford on 17th February. A Labour Hub long read.

When I was pondering the title of today’s talk, ‘past victories, future challenges’ seemed a good summary of what I wrote in my book, Champions of Equality which I researched from 2016 and published in 2017. But now the future I discussed in the book is already here, the challenges are now.

I’m a socialist by gut instinct, since my teen years, before I could even define the word; I’m a trade unionist by conviction, ever since I started my first job in a unionised workplace; and I’ve probably been gay since long before I recognised it, came out in my 20s, and began immediately to campaign for our liberation.

But before adopting any of these identities, I loved history, which is one reason why I decided it was necessary to write a book on the role of the labour movement in winning LGBT+ rights – the other being that the absence of such a study was a gaping hole in the vast literature created by LGBTQ+ people.

What right has a historian of the past to demand a hearing on the present and future? Some of you will be familiar with the phrase “those who do not learn history are doomed to repeat it”, said long ago by George Santayana. All aphorisms are simplistic and this one is no different: it begs many questions: not least, whose interpretation of history? And what lessons? But since it underpins my talk, I hope I can convince you!

My plan today is firstly to show how we managed to change the world we live in for the better, over a remarkably short period of time; alongside the critical part played in that by the labour movement – by which I mean here both trades unions and the Labour Party. Secondly, how this story itself suggests it is dangerous folly for LGBTQ+ people to be complacent about the legal rights we have secured.

Significant improvements

I have been privileged to have lived my whole adult life as a contributor to the bringing about of significant improvements in rights and public attitudes. First let’s recall the scale of the challenge.

Public attitudes to homosexuality

slow progress…

1963: 67% against decriminalisation of homosexuality [BRMB]

1965: 63% in favour of decriminalisation [NOP]

1975: 48% against being doctors or teachers. [NOP]

1981: 63% in favour of legalisation of homosexuality, 25% against; but 66% against being teachers [NOP]

1985: 61% in favour of homosexuality being legal [Gallup]

The impact of AIDS …

1986: 70% homosexual relationships mostly or always wrong [British Social Attitudes]

1988: 48% in favour of homosexual relations being legal [Harris]

And now…..

2014: 66% in favour of same sex marriage

Think about these poll findings. The much-talked about radical social changes of the 1960s had obviously not made much impact on the two thirds of people who wanted gay men’s very existence to remain illegal in 1963, but two years later those changes must have kicked in because the proportions seem to have reversed. I guess we all know the problems with relying on opinion polls.

Anyway, partial legalisation followed with the 1967 Sexual Offences Act, piloted by liberal-minded MPs and quietly encouraged by Harold Wilson’s Labour government. Then the 1970s was the time when the Gay Liberation Front – the ideology imported from the USA – was a dynamic and vocal part of a generational challenge to old social norms. The numbers actively involved were tiny, but they had an impact way beyond those numbers; and this decade also witnessed the first significant progress in gaining trade union support. Then came the reaction of the 1980s: the Thatcher years, the defeat of the miners, mass privatisation of public services.

But, at the same time, there was continued progress for LGBT people, helped by a flourishing of our community organisations and also political and practical support from Labour councils. We carried on fighting on many fronts for action and policies and legal changes despite a brutal political climate, and continued to have successes. That was until AIDS hit the UK – the impact on public attitudes was catastrophic as these numbers confirm. It is useful to note that although lesbians were among the groups least at risk from AIDS, media and popular prejudice was not bothered by the distinction and we were all lumped together as disease-ridden perverts – I don’t exaggerate: who could forget the full-page headline in the Sun, in gigantic type: “Gay Plague”, it screamed on 1st February 1985.

This time of reaction was given legal shape in 1988 with Section 28, the law that declared same sex relationships ‘pretended’ and illegitimate. You may know the story of this infamous piece of legalised homophobia. For years and years, even after it had been repealed, and despite never having applied to schools, it cast a devastating shadow over attempts to promote LGBT equality through the education of young people.

In light of these setbacks to our cause, you might ask: if things were this bad in 1990, how on earth did we get to the situation when, by 2010, a mere twenty years later, a procession of separate bits of legislation had disposed of, one by one, the great number of discriminatory and prejudiced laws under which we had lived and, in the Equality Act of that year, for the first time placed LGBT equality on the same level as all other groups protected by UK law from discrimination. The few remaining gaps do not detract from the main argument: a movement of a handful of young queers, campaigning alongside another, older, generation of people in organisations such as the Campaign for Homosexual Equality – who had been quietly lobbying away for decades to persuade politicians and people in influential positions that we are harmless and don’t deserve to be persecuted – had brought about an extraordinary transformation. The 70 percent in 1986 who believed that same-sex relations were always wrong and the 52 percent in 1988 who believed such relations also ought to be illegal – now meaning re-criminalised – had become a two-thirds majority who not only accepted we should be safe from discrimination, but even that – holy of holies – same sex couples should be allowed partnership rights. Even more astonishing, if you consider the previous history, it was a Tory prime minister who promoted same sex marriage in 2014.

What had happened?

Trying to explain social change is a fool’s game, but we have to make an attempt to identify some of the factors that contributed. And at this point let me add a precautionary note: if when examining this process we fail to identify that this was not a sudden, total conversion from prejudice to acceptance, we will also fail to appreciate some of the dangers that I will return to in a minute.

The role of the labour movement

The whole existing historiography of our equality struggle is fixated on brave individuals, on brilliant community initiatives, on lesbian and gay events, on our role in arts and culture. The list is very extensive and the bookshelves are weighed down by these stories. We should celebrate every single one of them. Without them we would not be here in LGBT History Month and its multiple focuses in the years since its creation – in 2006, when I was delighted to get the General Secretary of the TUC to host its launch at Congress House. We wouldn’t have the corporate buy-in to Prides – a double-edged sword, to be sure – and sponsorship of our activities. You know where I am going with this. The big hole in this history, the factor that I believe made a critical difference at national and local level time and again: where was the labour movement during these momentous years?

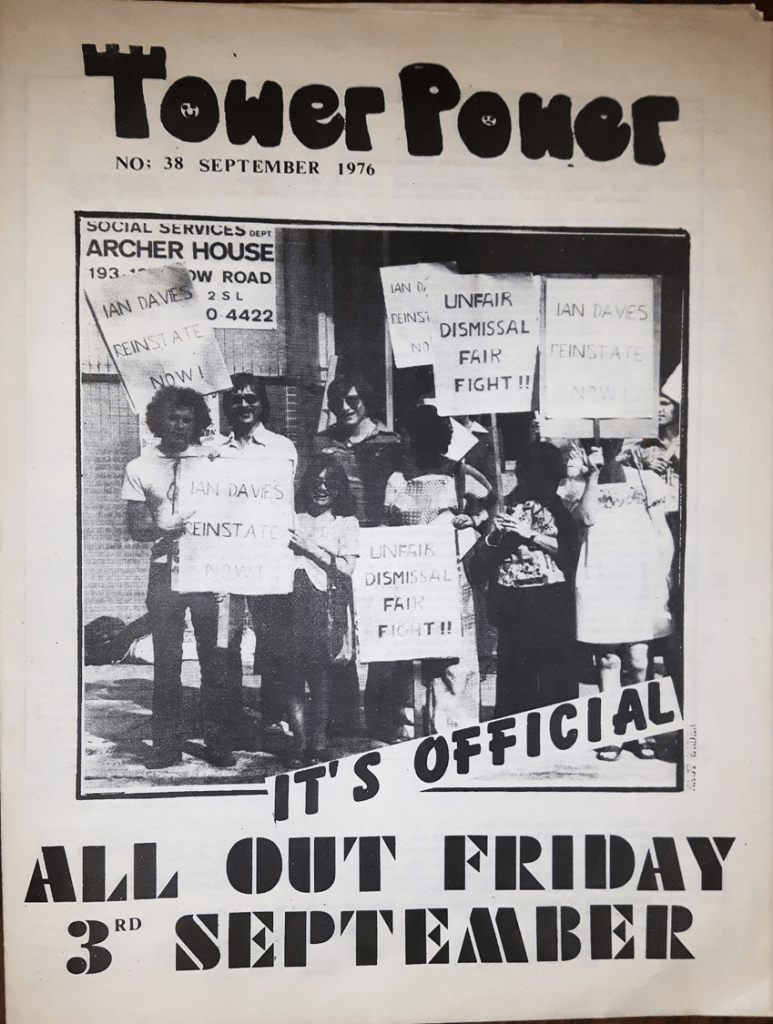

This is the front page of a trade union branch newsletter published in September 1976 – yes, even big union branches had to rely on gestetner duplicators in those days. Its content is historic. It tells the two thousand members of this branch of NALGO – the National and Local Government Officers association which is now part of UNISON – that they have voted to take strike action in defence of one of their members, Ian Davies, a gay man sacked by his employer, Tower Hamlets council, because he had advised them of a conviction for cottaging when he was entrapped by the police. When I was researching this for my book, I found that all the leading participants were still with us and I had the honour to meet and interview both Ian and the officers of that union branch. Ian had kept scrapbooks in which were preserved cuttings from local and national newspapers, which showed a predictable split between support for Ian and the Tory papers supporting his being sacked because it was unacceptable for a gay man to work with vulnerable people. The full story is in the book. The strike didn’t happen: but this was because the council backed down.

This case exemplified trade unionism at its best, a practical example of solidarity between workers; an illustration that the slogan ‘an injury to one is an injury to all’ was not empty verbiage. It wasn’t that 2,000 members of this union branch all believed in equal rights for LGBT people. But it was that they recognised that they needed to defend a fellow worker who had faced unfair treatment. The branch officers told me how they had been around all the various departments encouraging their members with exactly these arguments – and the results show how this had delivered the vote to go on strike.

I didn’t find – either in my researches, or in my own practical experiences in the 1970s and 1980s – that everywhere, suddenly, all that social hostility to our communities disappeared the moment you sat down for a trade union meeting. On the contrary, it was hard work. But over the 1970s and 1980s the trade union movement was convinced of its duty to defend lesbian and gay workers. The inclusion of bisexual and trans members took rather longer: I explore that in the book.

The chief drivers of this were LGB workers themselves. Sometimes they were also part of LGBT groups outside work, who understood two important facts: the first that workplaces were an important part in the lives of many LGBT people. We had no legal protection in the workplace against discrimination, in the worst cases no defence against dismissal, or we faced routine homophobia from managers or colleagues. I’ll expand on this first.

I interviewed many people for whom the notion that their identity as LGB or T was somehow separate from their life as a worker was ridiculous, and they had simply set about persuading their fellow trade union members of the same truths that the members of Tower Hamlets NALGO had accepted. If you are a trade unionist, you’ll understand that every union has its own history and culture and traditions of organising and its own democratic rules, so no two union stories are the same: but what was the same was that victory was gained initially by LGBT workers themselves getting organised, finding allies among straight colleagues, winning votes at branches and ultimately at annual conferences. There were setbacks along the way: trade unionists also read the Sun. An AIDS-influenced kickback led to the defeat of my first effort to win support at the biennial conference of what was then Britain’s biggest union, the Transport and General Workers, in 1987; but with a properly organised campaign and the support of union officers and leaders we reversed that defeat at the following conference.

That 1987 defeat was probably due to the reversal of the previously growing support for our equality among the wider public brought about by the AIDS crisis being reflected among trade unionists – not a surprise. But at the same time union officers and leaders were not bending to the tide of reaction: the National Union of Journalists, for example, commissioned non-discriminatory guidelines for its members to follow when writing about AIDS; and there were many stories, some of which I discuss in the book, where local trade unionists stood against the tide and organised support for members who had AIDS. These are inspiring stories of courage and basic humanity, the best of trade unionism.

The second fact was that in the bigger picture, trade unions were powerful cogs in society and might play a role in changing laws and attitudes. And not least that although, perhaps ironically, the most rapid and spectacular achievements in winning full union endorsement began in public sector unions that were politically unaffiliated – I mean NALGO, and the National Union of Teachers, now part of National Education Union – many were also part of the Labour Party.

I’ve mentioned how Labour-run councils had been amongst the first to back our campaigns and to provide practical support – Manchester was among the leaders but we should never forget the work done by the Greater London Council under Ken Livingstone, where John McDonnell led the work to fund the London Lesbian and Gay Centre.

1985 was a critical year. Despite the impact of AIDS, in September the TUC annual congress adopted a policy for lesbian and gay equality moved by the National Association of Probation Officers, for the very first time. The British trade union movement was now signed up. There had been a trial run earlier in the year when NALGO had successfully moved a similar motion at the TUC Women’s Conference – but this was advisory. Congress policy was not advisory, and now the British trade union movement could take its place among the growing list of organisations that stood for equality.

People outside the trade union movement often mock unions and I’ve debated with LGBT activists who say ‘Well, what took them so long?’ I reject that. Unions don’t change policy because an individual asks them to. A decade before, handfuls of LGBT trade unionists had met in people’s front rooms to discuss how on earth are we going to move this movement – at a high point encompassing 15 million members – those were the days! – to take up an issue where public discussion was either taboo, or else overwhelmingly reactionary. Turning words into action as a tiny minority in any large group is always challenging and at the start, even getting a hearing was difficult: but we did it, and, consolidated with the establishment of the TUC LGBT annual conference (from 1998) and appointment of staff to service it (me!), the trade unions were well placed to press for the legal and social transformation that culminated in 2010. And that is exactly what we did.

The second event that made 1985 critical was the vote, one month after the TUC, at Labour Party Conference, where – again for the first time – the Conference voted for a motion in support of lesbian and gay rights. I was a delegate from my Labour Party which had sent in the motion we had written in what was then the Labour Campaign for Lesbian and Gay Rights (now LGBT Labour). The Party leadership was terrified of media reaction – some things don’t change – but they couldn’t keep it off the agenda, as they had the previous year, because of the number of parties we’d persuaded to submit it. They did place it on the Friday morning slot, the very last, and they wanted us to remit it without a vote. We spent an utterly exhausting week lobbying, lobbying, lobbying, with our own fringe meeting, and handing out flyers at everyone else’s too. We gave top priority to lobbying trade union delegations. And we won, 58 percent on the card vote we’d called for. Better still, it was live on BBC TV. Trade union votes had been decisive.

Time after time, LCLGR took a motion to Annual Conference over the following years, but every time we won, with increasing votes – 97percent in the card vote on our 1994 motion – we had to keep going because the Party’s front bench spokespeople kept retreating from the commitment to equality. The work didn’t just involve Conference: we also pressed, met and lobbied Party leaders. We got there eventually. That’s why although Tony Blair was a reluctant ally, we had sufficient support among other ministers and MPs to keep progress on track through the creation of employment rights and civil partnerships and hate crime recognition and adoption rights and the Gender Recognition Act – I had to become an expert in so many areas of law! 2010 capped it off with the Equality Act, and just in time.

Also historic in that year of 1985 was that we had the backing of the National Union of Mineworkers. They gave us their votes – and their voices. They spoke in the debates, in repayment for the work of Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners – has anyone not seen the film Pride? If you haven’t you must, it’s billed as a comedy and there are some very funny moments, but for me, and not just because I knew and know the people who organised LGSM, it was a moving illustration of solidarity in practice and a real-life test of how such action can bring about social change in the most traditionally macho trade union.

Back in 2015, when I was still working at the TUC, we organised as usual for a trade union contingent on London Pride and that year, being the 30th anniversary of the miners’ strike, LGSM had come back together to re-promote that lesson of solidarity, around the launch of the film. At first – and in fact to my complete astonishment – the organisers of London Pride agreed to our suggestion that LGSM lead the parade. They quickly changed their minds when it was pointed out that this also meant that the trade union section would follow them at the front. In solidarity, LGSM refused to break their historic link with the labour movement and instead marched where we were, in the middle. It was wonderful to see the massive public support shown as we marched through London behind a colliery brass band. But it was obvious to me that people were cheering us because to them we represented ancient history.

I said before that you risk looking stupid if you try to explain social change. There is no simple – or indeed single – answer. One can be fairly certain that the Labour governments between 1997 and 2010 would not have established our legal equality without the pressure from LGBT people ourselves: that was critical. It is also probable that it wouldn’t have happened if they’d thought they would lose a lot of votes for doing it. But how had we reached that happy combination of realities? My argument is that one factor – only one, but important – was what we had achieved working through the labour movement in the preceding decades, in changing the views of our fellow workers, and in winning support among politicians for the changes we needed.

Other people and groups were also significant – Stonewall, for example, set up after the campaign against Section 28, became, for the media, the public face of LGB rights – their welcome but belated acceptance of trans people came later. One certain fact is that our rights, our equality, did not fall, unbidden, into our laps, it was not the altruistic gift of heterosexual politicians. They had to be pushed – and I know, because I spent decades of my life helping with the pushing – to do the right thing. I’ll summarise this part of my talk, ‘past achievements’, by reiterating the astonishing fact that over just a couple of decades, a minuscule group of LGBT activists contributed to an extraordinary transformation in legal rights, and the change was only possible because it was accompanied by an equally remarkable reversal of long-held public attitudes, a combination of changes in which the labour movement’s role has been shamefully ignored.

Future challenges

I said at the start, and this should terrify us – we’re living the future now, and I want to explore how you can’t separate it from what has gone before. We all know the state of the world today. The critical point, for me, is to understand that nothing falls from the sky except rain and snow and nothing happens in a vacuum, and to try to make some connections. Most significantly, any complacency about the security of the achievements I’ve just presented is dangerous.

You will have noticed many gaps in what I’ve described thus far. Inside the labour movement, we were struggling for recognition alongside many others – all of them groups much larger in number. Women combatting sexism and misogyny; black people challenging racism; disabled people trying to gain any kind of hearing at all. And that many LGBT people are of course also women, or black, or disabled, or more than one of these identities. I didn’t talk about the steps we had to take to achieve recognition and inclusion in our own little sector for all these identities, but also for bi and trans people. At the TUC we addressed these and we took active steps to achieve inclusion for all.

I stress this because inclusivity is not optional, it makes us all stronger and its absence would be seriously damaging. And by this I don’t just mean including everyone who is LGBTQ+. I mean allying with, standing alongside, everyone else who is facing discrimination or persecution. Throughout my long years of campaigning I’ve frequently encountered racism or misogyny among gay men, always the dominant section of our ‘community’ – a word requiring to be seriously qualified. There were the struggles of lesbians to achieve equal status which forced many to set up their own organisations; the hostility faced by UK Black Pride in some quarters, an initiative I was incredibly proud to support from Day One; and another massive achievement led by a trade unionist, Phyll Opoku-Gyimah whom I was happy to call a friend, empowering black LGBTQ people facing exclusion from both LGBT and black communities, coming together to challenge both.

It would become repetitive to continue: we have a moral duty of inclusion and solidarity. But if the moral case isn’t enough, then remember that mutual solidarity is also a matter of self-interest.

You all know that the agenda of the far right, historically and today, includes racial ‘purity’ and traditional family values. The list of countries where neofascists are in power or challenging for it is – or ought to be – terrifying. In the once super-liberal Netherlands, a neofascist – incidentally himself gay, but then remember Ernst Röhm and the brownshirts – won the last election. Then there’s Russia, Italy, Argentina, Hungary, the scary advance of the AfD in Germany and of the far right in Scandinavia. We don’t have to wait until November to know what the modern US Republican party wants to do: bans on abortion were sadly predictable. But libraries banning books and teachers being sacked for promoting LGBT equality in the country that prides itself on protecting even the most obnoxious free speech – if that doesn’t send shivers down your spines, it should.

Nothing like that could happen in Britain, could it? The polls are unanimous in predicting a Labour government some time this year. LGBTQ+ people are safe, aren’t we? Well, look at this.

Public attitudes 2017

50 years after decriminalisation…. One year after the Brexit vote … attitudes surveyed by YouGov, July 2017

Gay sex is unnatural: 42% agree overall; 69% of over 65s; 22% of aged 18 to 24.

Primary school should not be taught about same sex: 48% agree overall; 68% of Tory voters; 75% of over 65s; 26% of aged 18 to 24.

Gays should not become parents: 36% agree overall; 36% of Tory voters; 64% of over 65s; 16% of aged 18 to 24.

[Reported in The Independent, 27 July 2017]

This survey was conducted on the 50th anniversary of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act. Its findings contain both good and bad news. The good news is that so many younger people have accepted us. There’s hope there for the future. The bad news is not that so many people of my generation still don’t think we deserve equality: it’s that these are some of the people who previously did think – or at least, did say that, but have now either grown reactionary with their increasing years or else are empowered to say what they really think. That’s what I meant when I said earlier we have to dig deeper into headline statistics. Let’s make a comparison. My own view is that after years of hammering away at the anti-racist message, many people accepted it; but many others instead decided it was no longer respectable to be racist, so when asked, they would say what was expected, not what they really thought. It went underground. Did the same thing happen with our equality? Well, why shouldn’t it be the same? Now we can see how racism has resurfaced in a big way. Hold this thought and look at this.

Hate crime statistics – from the Home Office, as reported to the police (not reported for 2019/2020)

Category 2017/18 2018/2019 2020/2021 2021/2022 % increase in last year

Sexual orientation 11,592 14,472 18,596 26,152 +41%

Transgender 1,703 2,329 2,799 4,355 +56%

For comparison (these numbers rounded up or down)

Race 110,000 +19%

Religion 9,000 +37%

Disability 10,000 +13%

These are the Home Office figures for hate crimes reported to the police where the grounds of the crime were homophobia and transphobia. Pause to take them in, please. Then tell me that you believe we still live in a country where it is safe to be LGB or T. The Home Office tells us some of the increase – hate crimes have more than doubled in the five years reported here – is due to increased reporting. Well, two points: they’ve been saying that since they started collecting these figures, and there will be some truth in it. But, more important, is the known fact reported by Stonewall, that only one in four crimes is reported – because people don’t trust the police.

I can’t think why, can you? Anyway, try multiplying these numbers by four.

I put in the most recent figures – I rounded them – for the other types of hate crime so you can see that there are increases across the board. But also note that horrific although every one of these is, the increase in homophobic crime is greater than any other – apart from trans hate crimes.

Every year we commemorate trans day of remembrance on 20th November, where the deaths of trans people across the world are remembered. No, not deaths – murders – hundreds every year. How many trans people do you know? I’ll guess it’s not many. Proportionately, the violence against trans people is greater than any other group in society. As the case of Brianna Ghey tells us, that includes murder, in ‘safe’ Britain.

What more need I say: my message is obvious. So-called culture wars are the last resort of desperate bigots, racists and reactionaries clinging to power, knowingly inciting hate – because words have consequences. You have only to look again at the hate crime figures. Or are they too stupid to understand that there’s a connection? Real people are dying or having their lives shattered.

I don’t know what will happen in Britain – but never think that a law made cannot be unmade. Why should equality rights in Britain be immune to the actions of a future, far-right-led Tory party? They’ve already shown scorn for health workers, hatred for trade unionists, contempt for foreigners (unless they’re rich), disdain for international law.

No outcome is predetermined – any more than the climate catastrophe which is looming and may make all of this irrelevant unless we show a bit more courage in facing up to it. What we can do is build and maintain alliances of all who believe in equality and human rights, an alliance in which the labour movement must be central. This comes with a real life challenge: that of never yielding one inch – one millimetre – to the rhetoric of the far right.

I conclude with my own modified edition of the famous words spoken first in 1946 by the German Protestant pastor Niemöller. He originally supported the Nazis and welcomed their attack on the Communist party, so his words began with them. I’ve updated it for Britain in 2024:

First they came for the asylum seekers

And I did not speak out because I was not an asylum seeker.

Then they came for trans people…

History never repeats itself the same way: but there are enough warnings here to suggest that if we don’t learn from our history, we will regret it.

Dr Peter Purton is the author of ‘Champions of Equality: Trade unions and LGBT rights in Britain’ (Lawrence & Wishart, 2017).

Image: Lesbians & Gays Support the Miners – Mark Ashton Trust https://www.flickr.com/photos/p_de_vries/19227195465 Creator: patrickdevries2003 CC BY-NC-SA 2.0 DEED Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic