Mike Phipps looks at a new Compass report on the issue.

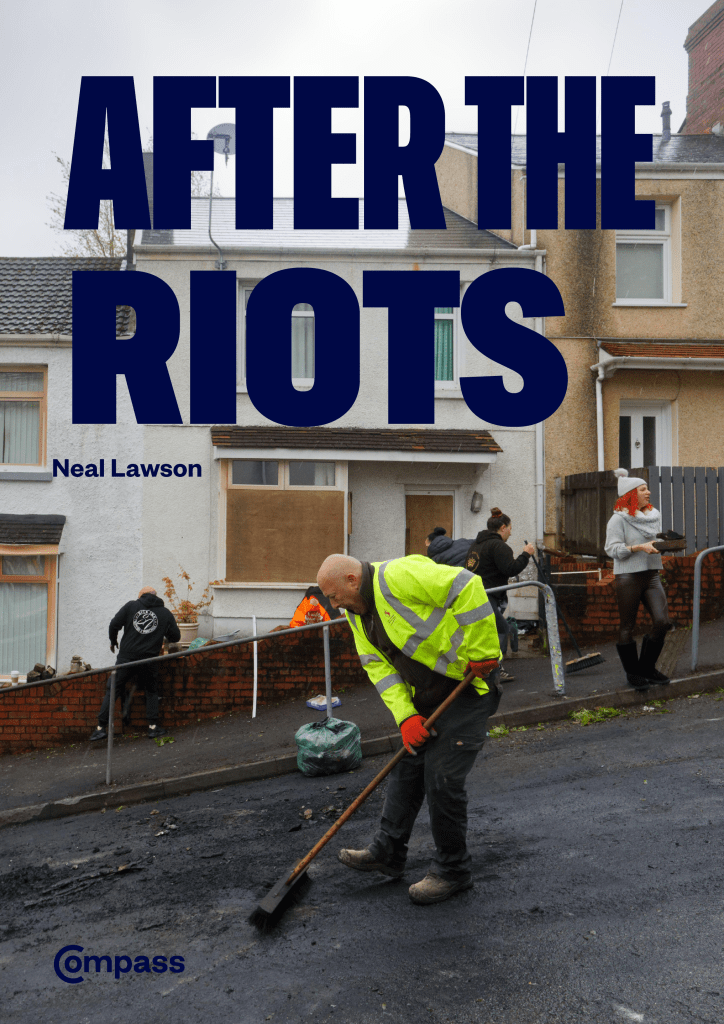

After the Riots is new report from Compass, the centre-left pressure group for a better, more equal, democratic and sustainable society. Written by Neal Lawson, the group’s Executive Director, it promises to “think big and deep, and look at the causes of the riots and their cures.”

The riots, notes the report, happened in a context “where there is no hopeful narrative around diversity and difference, around our obligations as a rich nation to the poor and the persecuted.”

That seems a bit sweeping, because actually there is such a narrative. It is not often articulated at national level, but it is promoted in London, for example, by Mayor Sadiq Khan. We heard it too from a previous mayor Ken Livingstone after the terrorist attack on the capital in 2005, when he said, ““Nothing you do, however many of us you kill, will stop the flight to our cities where freedom is strong and where people can live in harmony with one another.”

The background to 2024’s riots was one of a long-standing demonisation of migrants by the Tory government – and a Labour Opposition that complained the government was not being tough enough in dealing with ‘the problem’.

But the Compass report also argues for a wider background context to be considered. Given that seven out of the ten most deprived areas in England were involved, it’s clearly right to foreground Britain’s industrial decline, the dire state of its public services, the proliferation of real poverty, the breakdown of the bonds of society, the rise of consumption-driven alienation and the erosion of democracy.

But the link between decline and the riots cannot be viewed simplistically. Many people travelled to the flashpoints from outside these areas. There is a bigger picture to be considered here.

The far right

A critical focus must be on the role of the far right and its influence on social media. After all, this is not merely a domestic problem. A few years ago, ‘Tommy Robinson’ was the most well-funded politician in the country. A Guardian investigation exposed how he received “financial, political and moral support from a broad array of non-British groups and individuals, including US thinktanks, right wing Australians and Russian trolls.” The rise of the far right is global and its causes are complex. But it is fuelled by the huge sums of money it is attracting internationally.

The role of the mainstream media and much of the centre right Establishment also helps explain the rise of the outside right. Nigel Farage, for example, long before he was an MP, was one of the most frequent guests on the BBC politics panel show Question Time.

Commenting on last year’s victory in the Dutch general election by Geert Wilders’ Party for Freedom (PVV), Jacobin’s Helmer Stoel said: “Geert Wilders won the Dutch Election because the Establishment indulged him,” adding “The normalization of the Dutch far right was facilitated by outgoing Prime Minister Mark Rutte whose centre-right VVD party increasingly renounced its own liberal values, and embraced the language of the far right, with Rutte speaking ever more about the “refugee crisis.”

Professor Stijn van Kessel agreed, saying Rutte “legitimised Wilders’s agenda by making immigration a key issue in its campaign.” As in the Netherlands, the UK’s problem is that the far right’s agenda – and some of its key leaders – have been normalised by the mainstream right for narrow political advantage.

Neither coherent nor compelling

Unfortunately this problem is not really explored in the report. It says of the riots: “This is what can happen when the right and the far-right organise ambitiously, coherently and internationally, across borders to win the big battles, when they tell more compelling stories of loss, nostalgia, blame and fear, while progressives think small, act smaller, offer too little credible hope and retreat into their silos, logos and egos.”

This strikes me as wrong on a number of counts. Firstly, the far right message is neither coherent nor compelling. It’s clear that the use of a piece of fiction about the ethnicity of the alleged Southport murderer to whip up racial hatred demonstrated an element of desperation by those who incited the riots. The ousting of one of the most xenophobic and right wing Tory governments in modern times was now depriving them of the most influence among the governing elite their ideas had ever enjoyed and they lashed out accordingly. But as with pogroms elsewhere, the preparations had been laid long in advance, right down to the collation of data about the location of migrant hostels.

Secondly, there was nothing “compelling” about what the far right was inciting. Despite similar dehumanising language about migrants being used by many mainstream right wing politicians and media outlets, most people are repelled by this rhetoric – and came out on the streets in large numbers to show it.

Opinion surveys underline this. Professor Rob Ford argues that although migration is at record highs, the long term trend in public support for restricting migration is downwards. In Britain, “more British people now than ever before see migration as both economically and culturally beneficial.” Yet you wouldn’t know this from the mainstream media’s and political elite’s framing of the issue.

Thirdly, the dig at “progressives” in this context is really misplaced. The notion that progressives have marginalised themselves by their own limited imaginations is not supported by the facts. Progressive ideas have to a great extent been forcibly driven out of the Labour Party by the most ruthless, factional, organisational methods. The author of this report has himself been on the receiving end of such bureaucratic treatment.

The mainstream media have also been complicit in erasing the radical political alternative put forward by Jeremy Corbyn MP when he was leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2019 and whose performance in the 2017 general election gained the largest Labour vote share since 1997 and deprived the Tory government of its majority. The accusation that the left’s supposed self-obsession has allowed its natural constituency to fall into the clutches of the far right is, as I have argued elsewhere, a bit trite – and more importantly mis-characterises the participants in the riots.

The riots were not a working class uprising but a pogrom, as underlined by their targets – migrants, but also a library and a Citizen’s Advice Bureau. Which is why the report’s statement that “This is what can happen when the speed and scale of cultural change is too much for some of the poorest and the weakest to keep up with” must also be questioned. CABs have been around sine World War Two, libraries far longer. Destroying them can hardly be seen as a response to the “speed and scale of cultural change.”

A better framing

There are better ways to frame the issue. The real question is why hasn’t there been real progress on social equality in this country in the same way that there has been on racial and gender equality? In fact, the journey to a more socially equal society has gone backwards in the last forty years. It’s this contradiction that social media influencers who want to reverse the gains made on gender and sexual orientation also tap into when they peddle their online misogyny and homophobia.

It needs underlining too that the riots were not just about migrants – they had a wider racialised character. In some cases, anyone who was black or brown was being targeted – people were even being stopped in their cars.

It’s not just the prevailing climate of official hostility to migrants that forms the backdrop to these events. For the last eleven months, both Government and Opposition have ignored the war crimes and breaches of international humanitarian law that have characterised Israel’s genocidal assault on Gaza. In doing so, they normalise violence against not just Palestinians, but people of colour more generally. If it’s OK for Israel to behave in this way, why not others? runs the rationale.

More than two decades of negative stereotyping of Muslims also lent a strongly Islamophobic content to these riots. It was noteworthy that Keir Starmer, in his condemnation of them, could not bring himself to use this term.

The Compass report rightly recognises that any ‘solution’ that focuses on being ‘tough’ on migrants and on rioters will only give succour to the right. This is correct: further demonisation of migrants after more than a decade of a hostile environment policy will only encourage more anti-migrant activity on the streets. But, equally, the punitive sentencing policy of jailing so many people in overcrowded and unstable prisons will solve nothing in the long term and is largely performative on the part of the authorities – similar to the tough sentencing of those involved in very different riots over a decade ago.

Questions and answers

The report doesn’t claim to have all the answers, but says it seeks to ask the right questions. It poses eleven, some more open than others. The first is: “How do progressives learn to talk about the nation as a legitimate space in which the rules of society are decided and followed, a place we can all be proud of?”

It’s an interesting question, but also something of a red herring in a report into racist pogroms. A survey this month suggests that pride in our history as a country has fallen sharply over the last decade. This has quickly turned into a right wing talking point.

But the survey also found that people are embracing a more inclusive and self-critical sense of Britishness, which probably means that progressives are indeed talking about the nation more, but not uncritically, nostalgically or using exclusionary categories.

It’s a bit outdated to suggest that the left cannot engage with these issues. If anything, the Labour right has more difficulty with patriotism. Its candidate in the May 2021 Hartlepool byelection handed out St George’s Cross flyers to voters and it did him little good. The Tories inevitably win such crude patriotism contests.

Interestingly, it was Gareth Southgate who taught Labour – and the country – how to engage with the idea of nationhood. His dignified “Letter to England” in defence of the England men’s football team practice of ‘taking the knee’, expressed the pride the England team felt in representing their country, before affirming: “I understand that on this island, we have a desire to protect our values and traditions — as we should — but that shouldn’t come at the expense of introspection and progress.”

A more straightforward question asked in the Compass report is: “Where do we find the resource to invest in jobs, communities and public services and enrich our social soil instead of allowing it to be degraded?” The answer is clear: Britian is one of the richest countries in the world. If its government prefers to raise the cap on energy prices, abolish pensioners’ winter fuel allowances, retain the bedroom tax and two-child benefit limit and talk about the need for more austerity after fourteen years of benefit and service cuts, rather than raise taxes on the wealthy and corporate sector, that is a simple policy choice.

The resource s are there, if the government chooses to utilise them. But that depends on whether they prioritise the wishes of the voters over those of the corporate lobbyists. As Labour peer Prem Sikka tweeted recently: “JP Morgan CEO Jamie Dimon to meet chancellor Reeves ahead of the Budget. Agenda – more privileges for banks/corporations. How easily can hungry children, freezing pensioners, poorer households meet ministers to demand change?”

The report is clearly asking some of the right questions. “How are citizens to be given a meaningful voice locally?” Well, we could start by restoring greater financial autonomy to councils, that was lost when the Thatcher government removed the power of local authorities to set business rates.

“Can social media really be effectively regulated?” Brazil clearly thinks so: its Supreme Court has upheld a ban X (Twitter) for breaching the country’s rules on social media platforms. But the longer term problem of such platforms being owned by unaccountable billionaires with extremist views can be solved only by developing accountable publicly owned alternatives that ban disinformation and hate-speech.

An enquiry into extremism?

The report concludes by calling for, as an immediate first step, a Public Inquiry into the Causes and Cures of Political Extremism, “tasked with examining all forms of political extremism.”

However, this is a fudge. The problem here is right wing extremism, encouraged and fostered by mainstream right wing politicians and a supportive media.

In France, President Macron has repeatedly bemoaned ‘extremism’ of both left and right as though they are twins rather than polar opposites. This stance has led him to refuse to recognise the electoral victory in parliamentary elections earlier this year achieved by a popular front which was created specifically to counter the threat from the neofascist right. It should be clearly stated: anti-fascism – so-called ‘left wing extremism’ – is not the issue.

The report is right to say that these riots were not the product exclusively of the last fourteen years of Tory government. But it’s equally clear that people voted for change in July’s general election. They want a break with the Tories’ corruption and cronyism but also the economic choices that have produced deep, widespread poverty and decimated public services. And they want those changes to come soon. The recent gains by the far right in Germany show what can happen when a centre-left government ignores people’s demands for improved public services and solutions to the cost of living crisis and sticks to the same old neoliberal economic agenda. As Keir Starmer’s ratings continue to slide, this warning takes on a new urgency.

After the Riots, by Neal Lawson is available here.

Mike Phipps’ book Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: The Labour Party after Jeremy Corbyn (OR Books, 2022) can be ordered here.