As Labour Conference meets, Mark Perryman provides a reading guide to the hopes, and the fears, of what Keir Starmer’s government will achieve. . A Labour Hub long read.

July 4th 2024: a Labour landslide of historic proportions. We can argue the toss about turnout, vote share, the rise of the Greens and Independents but a Labour win is a win, and perhaps more joyously a Tory defeat, a defeat. Hurrah!

For an instant account of Labour’s campaign, look no further than Taken as Red: How Labour Won Big and the Tories Crashed the Party by Anushka Asthana. The access and contacts via her role as ITV’s Deputy Political Editor and prior to that Chief Political Correspondent on The Times opened almost every door imaginable. Readers will have differing views about what many of the campaign revelations tell us about Keir Starmer’s Labour, but all will find them spellbindingly interesting!

Of course, Labour has spent considerably longer in Opposition than in office. For those of a certain vintage, etched in the memory are Wilson and Callaghan’s five years, Thatcher and Major’s 18 years, Blair and Brown’s 13 years, Cameron’s (with a little help from Clegg), May’s, Johnson’s, Truss’s and Sunak’s 14 years. Add it all up: that’s 32 years of Tories versus 18 years of Labour. So it seems appropriate to start with Mark Garnett, Gavin Hyman and Richard Johnson’s Keeping the Red Flag Flying: The Labour Party in Opposition since 1922. Quite how ‘red’ that flag has been for the best part of a century readers will no doubt argue the toss over.

To help settle that never-ending argument look no further than A Century of Labour by Jon Cruddas, marking the centenary of the first Labour government of 1924 with an unashamedly partisan account of the Party’s record when in power ever since. It’s written by the major figure of the short-lived post-Blair ‘soft left’, an a force that has much weakened to the point of absence, notwithstanding Labour’s well-worn claim to be a ‘broad church’.

A shorter time span, but one more familiar to readers of a certain age, is admirably covered by Patrick Diamond’s The British Labour Party in Opposition 1979-2019: Forward March Halted. Though what would the much-missed Eric Hobsbawm, author of the original The Forward March of Labour Halted? in 1978, have made of the Miliband -Corbyn-Starmer years? Now that’s a question!

Instead of a broad Party, Labour has become increasingly polarised. It’s a Party of polar opposites with the Labour right ruthlessly suppressing its opposite number. For Tony Benn, Ken Livingstone, Diane Abbott, John McDonnell and Jeremy Corbyn collectively, the badge ‘hard left’ is worn with considerable pride. It’s a tendency that, post-Corbyn, has gone the same way as the soft left, bordering today on extinction.

Andy Beckett tracks the evolution of this tendency through the years of growth, the 1970s framed by the victorious 1972 and 1974 miners’ strikes and the emergence of Bennism in When the Lights Went Out. And he followed this with Promised You a Miracle, the early 1980s’ reign of Thatcherism triumphant, the Falklands War, the end of the Bennite insurgency and a hapless Labour Party led by Michel Foot.

In his new book The Searchers: Five Rebels, Their Dream of a Different Britain, and Their Many Enemies Andy revisits the beginning, middle and end of this history-in-the- making to bring it bang up to date and makes a compelling case for what the Party of the ‘broad church’ loses when the hard left, from Benn to Corbyn, is forced into involuntary absence. It’s a Labour left that, whatever its faults – that would be the subject of another book – mixes heady idealism, dogged determination and more fresh thinking than they are often given credit for. The narrowing of this breadth to exclude almost any version of the left that Keir Starmer and his enforcers don’t approve of is Keir’s signature achievement in terms of how he runs the Labour Party.

Diane Abbott’s memoir A Woman Like Me is an absolute testament to what Labour loses when this narrowing goes unchallenged, recognised across Labour’s spectrum with the breadth of resistance to Keir Starmer’s ill-conceived plan to ban her from standing in the 2024 General Election. It’s a book with a rich vein of humour, intended or otherwise. Read Diane’s account of her romance with Jeremy Corbyn and just try to stop yourself laughing out loud!

A new generation of thinkers and writers who orient around Labour manage to combine critique with an unwillingness to write off the Party in government as an agent of change for the better. Futures of Socialism: ‘Modernisation’, the Labour Party, and the British Left, 1973-1997 by Colm Murphy expertly tracks the evolving, and sometimes competing, debates as Labour shifted over the course of two and a bit decades from The Alternative Economic Strategy to the abandonment of Clause Four. The shift from Corbynism to Starmerism has been considerably swifter: we await to see for better or worse.

Karl Pike in his Getting over New Labour: The Party after Blair and Brown makes a compelling case for not conducting any assessment of Starmer in terms of compare and contrast with 1997-2020. Instead, he urges we understand that, while identifying continuities has its place, accounting for the differences is far more interesting and important.

My stand-out title for making sense of Starmer in power is a book from Eunice Goes. Her short book Social Democracy is a handy ready-reckoner of how social democrats, epitomised today by Keir Starmer and Rachel Reeves, seek to square the circle of the radical and democratic, or as Labour’s General Election campaign oxymoronically sloganised ‘Change and Stability’. One quibble: this superb 176-page paperback guide is priced by the publishers at £24.99, a price more than enough to put off the general readership it richly deserves.

And the Tories? Phil Burton-Cartledge can justifiably say ‘I told you so’ until the end of his days. The Party’s Over: The Rise and Fall of the Conservatives from Thatcher to Sunak was originally published as Falling Down in 2021. Back then, Boris Johnson was still basking in the vainglory of his 2019 landslide and the comprehensive breaching of Labour’s red wall. Few doubted Labour was in deep trouble and the Tories set for umpteen more years in power, certainly not the paid commentariat. Phil did doubt, uniquely revealing the underlying trends that would lead not so much as Labour winning in 2024 as the Tories losing.

If Labour is to turn 2024 into the basis of a victory that lasts, more than anything it must transform an unequal Britain. Polly Toynbee’s writing exposing inequality is all the more effective, coming as it does not from the unrepentant left. Instead she expertly places the necessity of this transformation at the very centre of politics, gently egging Labour on both to recognise this and act upon it. Her latest book, with co-author David Walker, The Only Way is Up: How to Take Britain from Austerity to Prosperity should be essential reading for every Labour MP, adviser and campaigner, not only with an eye on winning again in 2029, but why it will deserve to do so.

By some considerable distance Danny Dorling is not only the most compelling author on inequality but the most prolific too. In 2023, Danny’s Shattered Nation: Inequality and the Geography of a Failing State provided a map of poverty’s impact across all points of Britain, north, south, east and west – a kind of Road to Wigan Pier, with the statistics. Then earlier this year, his Seven Children: Inequality and Britain’s Next Generation added a biographical dimension of children’s lives and aspirations from across the income bracket that every parent and teacher will readily recognise and any Labour government should seek to change.

And now, just in time for Labour Conference comes Peak Injustice: Solving Britain’s Inequality Crisis, a primer of richly ambitious yet entirely practical policy ideas that is essential reading for anyone who wants Labour in power to fulfil its promise of ‘change’ with changes that would rapidly affect for the better those most urgently in need of change.

Mary O’Hara’s new book Austerity Bites 10 Years On: A Journey to the Sharp End of Cuts in the UK revisits the places and communities she first wrote about in her 2014 book, Austerity Bites. Since then, what has another decade’s worth of Tory socially-engineered desolation achieved? Read it and then ponder what Labour in the likely scenario of two terms could achieve in the next decade to reverse this unwanted legacy.

For an account of when governments fail in such a project, and instead cruelly worsen the situation of those who can least afford it, read The Department: How a Violent Government Bureaucracy Killed Hundreds and Hid the Evidence. Disabled activists recently raised the money to deliver a free copy of this extraordinary book of investigative journalism by John Pring, himself disabled, to every one of our 650 MPs. Let’s hope they not only read it but act upon it too.

The mining valleys of South Wales occupy a special place in left folklore. The 1926 General Strike, the miners who joined in their hundreds the International Brigade to fight fascism in Spain, the Aberfan disaster of 1966, the miners’ strike of 1984-85 – and that’s just for starters. Brad Evans puts the present, poverty-stricken plight of the valleys in the context of this uniquely heroic past. How Black Was My Valley: Poverty and Abandonment in a Post-Industrial Heartland is a read both to anger and inspire. The first is worse than useless without the latter. Brad wonderfully achieves this vital combination, and then some.

After 14 years of Tory-engineered inequality, Satnam Virdee’s and Brendan McGeever’s all-embracing account and solutions too, Britain in Fragments: Why Things are Falling Apart is my first choice as a book to read, inform and inspire. They put this entire sorry tale of inequality, injustice and austerity into one account, every bit as much about problem-solving as problem-accounting – no easy task. They achieve it by explaining why democratic reform, the renewal of a failing welfare state, a popular anti-racism, a reinvention of class politics and recovering from Brexit are all interlinked as solutions to a failing system.

Meanwhile Keir Starmer’s in-tray is full of a host of issues, each pressing for urgent and radical attention. The first signs of response should give at least some grounds for optimism. The much-missed socialist writer David Widgery castigated a left mired in ‘miserabilism’, a version of politics guaranteed to de-motivate and achieve diddly-squat in the process.

In Louise Haigh, alongside Angela Rayner and Ed Miliband, Keir Starmer’s Cabinet has at least some breadth, though it’s restricted of course by Cabinet rules of ‘collective responsibility’. Nevertheless, each has already spearheaded the rapid and radical implementation of policies on transport and green energy.

How the Railways will Fix the Future: Rediscovering the Essential Brilliance of the Iron Road by railway engineer and RMT member Gareth Dennis sets out in expert detail the huge potential of an entirely publicly owned train system, run for the benefit of serving communities, and a key resistance to the rapidly emerging climate emergency. And attractively priced at just £10.99, it’s cheaper than most currently overpriced train tickets!

For a generation of urban voters rent and landlordism is an absolutely central issue. The Rentier State: Manchester and the Making of the Neoliberal Metropolis is Isaac Rose’s powerfully argued examination of how a direct, statist, challenge to the rental industry would be just about the most popular policy Labour could enact to help restore the Party’s increasingly fragile support in what were previously Labour’s metropolitan urban heartlands. Yes, rent controls and ending no fault evictions are a welcome start, but what about who owns the properties in the first place?

Will Labour make such a challenge? Grace Blakeley outlines in Vulture Capitalism: Corporate Crimes, Backdoor Bailouts and the Death of Freedom both precisely why it should and won’t. From housing to football clubs via high street fast food outlets to almost every part of the country’s manufacturing sector, ours is an economy, a society even, entirely owned by global corporations. And as Grace patiently explains for the non-specialist reader, the failure to challenge this salient fact is absolutely rooted in Labour’s inability to recognise how it is neoliberalism that has afforded this takeover.

The Spanish Civil War, the Soviet crushing of the Hungarian revolution, the Vietnam War, apartheid South Africa, Iraq – each in their different ways shaped a political generation. And each in their different ways distanced that generation from Labourism as an institution, body of ideas and vehicle for undiluted progress. In 2024, Gaza is doing the same. Despite, once again, some early moves in the right direction; the partial arms ban, restoring some humanitarian aid funding, not opposing the legality of the indictment of Netanyahu as a war criminal, for today’s political generation this isn’t nearly enough and the idea that this disconnect will pass with the passage of time a dangerous fiction.

For an insight into why Gaza won’t simply disappear as a cause, read Israeli journalist Gideon Levy’s courageously dissenting reportage on both the horrors of 7th October and the punishment of Gaza via mass devastation and killing in The Killing of Gaza: Reports on a Catastrophe. And for the historical background, Israeli historian IIan Pappe’s Ten Myths about Israel is an absolutely essential read. Note, Gideon and Iian are both Israelis and Jewish; their parents fled Europe to what was then Palestine in the 1930s to escape the Nazis. Remember this when reading these two extraordinary books and the foul assertion that to be a critic of Israel and its guiding ideology, Zionism, is to be antisemitic.

The not much lamented Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP) in the 1980s had a certain political presence via its daily paper Newsline, well-funded local youth-training centres, and its most prominent members, Vanessa Redgrave and her lesser known brother Corin. Behind all this was one Gerry Healy, and when his multiple sins were finally revealed, the WRP split in time-honoured fashion in multiple directions, all claiming of course, to be the one and only ‘true’ WRP. The Party is Always Right: The Untold Story of Gerry Healy and British Trotskyism by Aidan Beatty tells this entire sorry tale in highly readable and fascinating detail.

Paul Foot would have denied it, via a vigorous and richly humorous polemic, but as a Trotskyist and, to use the vocabulary, ‘leading member’ for most of his life of a Trotskyist party, in Paul’s case, the Socialist Workers Party (SWP), he shared a not entirely dissimilar political outlook to Healy. But then in so many other ways they couldn’t be more different. He was a supremely gifted writer, dogged investigative journalist exposing injustice where he could find it, his journalism every bit at home in Private Eye, the Daily Mirror, the London Review of Books as Socialist Worker, a revolutionary who counted Shelley and Orwell as much an influence on his politics as Lenin and Trotsky, and most of all one of the finest and funniest orators for the cause one was ever likely to hear.

All this and more is retold in Margaret Renn’s biography Paul Foot: A Life in Politics. And if readers find it difficult to believe that an unashamed democratic socialist of a reformist disposition like me could find so much to admire in a revolutionary socialist (and a Trot for goodness sake!), read Paul’s final book The Vote: How It Was Won and How it Was Undermined to find out why.

As for the theorising of the far left much of it I can do without, no thank you very much. But in amongst the spurious rewrites of 1917, in the 2024 remix, there is a depth of thinking us lightweight reformists would do well not to dismiss. AntiCapitalist Resistance (yes, really) is the stillborn descendant, after many splits and versions along the way, of arguably the most creative of the 1968 crop, the International Marxist Group (IMG), whose best known member was another brilliant writer and orator, Tariq Ali.

The Resistance’s (no, don’t laugh) have recently published Palestine and Marxism by Joseph Daher which, refreshingly free of the 1917-era jargon, provides a theoretical framework to understand Gaza for a much wider audience that the revolutionary left would do well to engage with, if not entirely subscribe to.

These groups, and as the saying goes there are 57 varieties and counting, number a few hundred members each. Only the SWP and the most definitely non-Trotskyist but proudly revolutionary all the same, Communist Party of Britain (not to be confused with its sometime forebear Communist Party of Great Britain 1920-1991 with which they share virtually nothing in common except the similar moniker) number in the few thousand. None have anything like the reach of the hero of the TV and radio station studio take-down of all things establishment, including the Labour Party establishment, RMT General Secretary Mick Lynch. Gregor Gall’s Mick Lynch: The Making of a Working Class Hero meticulously analyses Mick’s irresistible rise as the polar opposite to Keir Starer’s rise over roughly the same period.

Will Mick prove to be Keir’s worst nightmare? This is my top choice of a read to give an understanding of the most effective opposition Keir could face if his promise of change fails to deliver improvements for the many and leaves the few’s wealth unscathed (to adapt a Corbynist, via Shelley, slogan). It’s a book which gives a very good idea of how Mick, and, arguably the equally combative yet more successful in terms of industrial action, Unite’s Sharon Graham, might be key figures to shape precisely this kind of opposition.

Not that a resurgent, and campaigning, trade unionism will be sufficient, not by a long way. There is a now a deeply rooted tradition of social movement organising that absolutely must be part, parcel and central to any movement committed to ensuring we receive the very best this Labour government can deliver. That tradition in many ways has its roots in 1970s second-wave feminism, the interaction of socialism and feminism epitomised by the publication in 1979 of the path-breaking Beyond the Fragments, co-authored by Sheila Rowbotham, Lynne Segal and Hilary Wainwright. Sheila revisits the immediate political aftermath of the book’s publication in her latest memoir Reasons to Rebel: My Memories of the 1980s, a beautifully written reminder for those who were there for the early years of Thatcherism. It’s a brilliantly written social history for those who weren’t.

Edited by Joshua Virasami, A World Without Racism: Building Antiracist Futures helps us to understand the very welcome fact that in the 2000s, antiracism has become every bit an irresistible force of change as feminism did in the 1980s, most recently via the huge global response to the Black Lives Matter movement. Joshua has expertly curated a wide range of contributions, including on solidarity and internationalism, antiracist tenants’ movements and organising as migrants that help portray the depth of this welcome change.

In Multitudes: How Crowds Made the Modern World, Dan Hancox argues that social movements transform themselves into into mass movements via the symbolism of the crowd. It is the crowd on the move with a shared purpose which more than anything can evoke collective identity, a vibrant force for change, a joyful sense of being part of a movement. No, that’s not how I’d describe most London national (sic) demonstrations from A to B past row after row of bemused shoppers and tourists. But then that’s Dan’s point: planet placard isn’t the beginning and end of a politics of the multitude. It’s anything but.

Perhaps what this great movement of our imaginations needs most of all instead of a thought-out plan of action is a banner to rally behind. And fortunately rescued from ‘modernisation’ and dusted down all ready to go, we have one. Red Threads: A History of the People’s Flag is a book like no other, Henry Bell’s absolutely fascinating history of the Red Flag. C’mon as the song goes, raise the scarlet standard high!

Mmm, maybe even with a techno remix not quite the dance number to get down with Gen Z . ‘Brat’? I hardy think so. But at least the thought was there. Or as the anarcho-feminist Emma Goldman rather neatly put it, “I did not believe that a cause which stood for a beautiful ideal, for anarchism, for release and freedom from convention and prejudice, should demand the denial of life and joy.” Amen to all that, well except the anarchism. obviously. No fun, no thanks.

Toby Manning’s magisterial Mixing Pop and Politics: A Marxist History of Popular Music disavows all this. OK, I’ll admit the subtitle, “Marxist History” doesn’t exactly overflow with any suggestion of the pleasure principle as a founding basis for how we ‘do’ our politics, but stick with it. Over 500-plus pages provide a soundtrack ranging from doo-wop, soul and psychedelia to glam, punk rap and grunge. It had me crying out for more, more, more! Read and revolt against the ‘no fun’ brigade.

The moment this all made sense to me was when I first stumbled over what I thought ‘doing’ politics was all about. Victoria Park, Hackney, Sunday 30th April 1978, The Clash, Tom Robinson Band, Steel Pulse, X-Ray Spex: the Rock against Racism Carnival. Rick Blackman’s Babylon’s Burning: Music, Subcultures and Anti-Fascism 1958-2020 helpfully provides a richly-researched history of this clash of cultures, rebel music and protest politics, from the aftermath of the 1958 Notting Hill race riots to the rising tide of anti-immigration racism of the current decade.

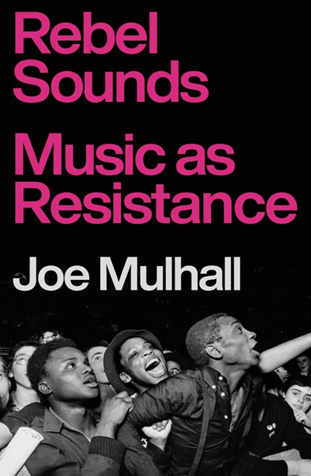

And top of my reading hit parade on the subject of music, culture and resistance is Joe Mulhall’s Rebel Sounds: Music as Resistance. Best known as a writer and researcher on modern-day fascism, there couldn’t be a better author to write a counterfactual account of an anti-fascism – and anti a whole lot more too of what is rotten in our society – rooted in music. It’s global in reach too, with Irish rebel songs, underground gigs in the old Eastern Europe behind the Berlin Wall, the music that helped topple apartheid South Africa, the soulful soundtrack to America’s civil rights movement. Joe recounts a politics that looks as good on the dancefloor as on the march.

I conclude this comprehensive Labour Party Conference reading guide with my five-star choice for the book to read as Keir Starmer’s Labour Government approaches its first 100 days in office on 17th October. It’s just 120 pages long, easy enough to digest in a day’s reading yet it couldn’t be more necessary and urgent to do so. The Little Black Book of the Populist Right: What it Is, why it’s on the march and how to stop it is by Jon Bloomfield and David Edgar.

The August race riots have been clamped down upon, but neither the very real causes of the problems behind them nor the violent response aimed at Muslims, immigrants and asylum-seekers, have gone away. Both the Far Right and the Populist Right will be doing their worst to keep this anger at inequality and austerity entirely rooted in a racist narrative. And across Europe it’s no better, but worse: Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands in thrall to the Populists and wannabe post-fascists. This short but brilliant book is both a road map to the nightmarish future where these first 100 days could end up and a helpful guide to why they don’t necessarily have to culminate with such a violently sorry ending by 2029. Read and resist.

No links in this review are to Amazon. If you can avoid purchasing these books from a site that both dodges taxes and exploits its workers, please do so.

Mark Perryman’s previous books include The Blair Agenda and The Corbyn Effect he is currently working on a new book The Starmer Symptom, to be published by Pluto in autumn 2025.