This global trade war could not have come at a worse time for the British economy, argues Michael Roberts.

US President Donald Trump has waylaid world markets with a barrage of tariffs on US imports. Nearly every day, the nature and direction of these tariffs have been varied, withdrawn and then re-imposed. On so-called Liberation Day, 2nd April, he introduced a list of ‘reciprocal tariffs’, which applied to practically every single country in the world, (including the penguin-only inhabited islands of Heard and McDonald, 2,000 miles south west of Australia).

He included an extra levy on Chinese imports in retaliation to China’s decision to impose a 34% tariff on US imports, which in turn was a retaliation against Trump’s 34% hike on Chinese imports proposed earlier. So US imports from China then had a 104% tariff rate, in effect a doubling. Then China announced a further 50% hike on US imports, taking Chinese tariffs on US exports to 84% in a tit-for-tat retaliation war.

The US bond market and the dollar tanked on the news. And so within days, Trump dropped these tariffs, except for China, and reduced the tariff hike to 10% across the board. Then American manufacturers of Chinese consumer electronic imports screamed that they would be wiped out if the double tariffs on Chinese imports were maintained. Again, Trump backed down and announced a ‘temporary’ exemption on tariffs for iPhones, iPads, laptops, TVs, etc., made by US companies in China. But it’s only temporary, apparently. And new tariffs on semi-conductor imports are in the offing.

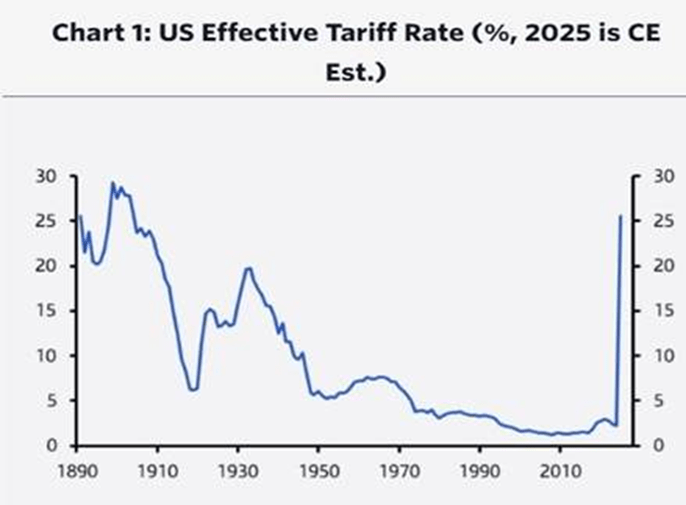

So despite Trump backing off from implementing his bizarre reciprocal tariffs, the tariff war is by no means over. The ratcheting-up of tariffs on China still leaves the US total effective tariff rate on all its imports higher than it was before Trump flinched.

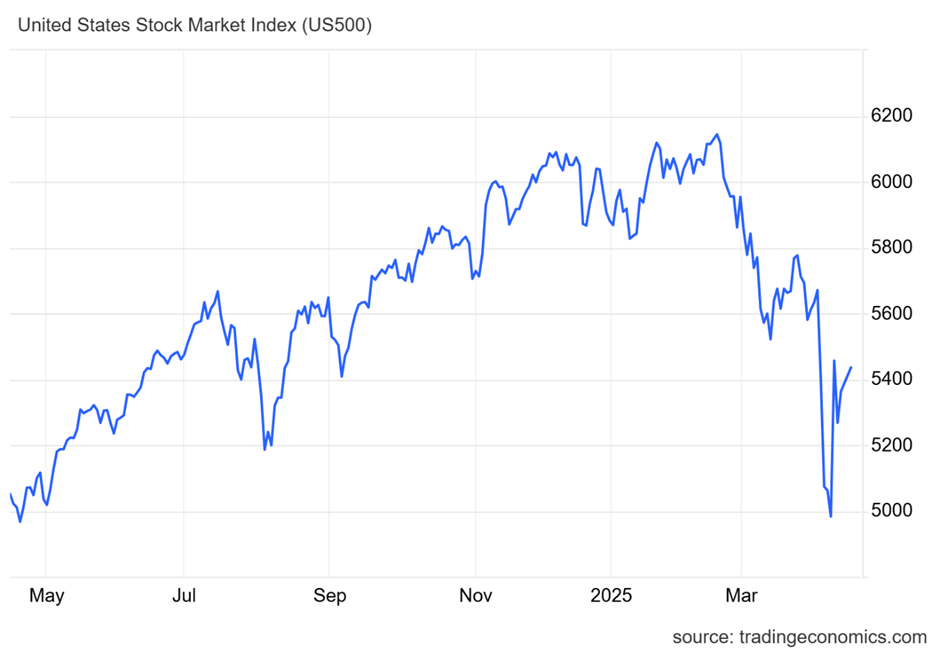

The madness goes on with financial markets in turmoil. The US stock market fell nearly 20% from its peak in mid-February and without any appreciable recovery when Trump backed down. Even more serious, US government bonds also plunged, threatening to cause a financial credit squeeze as hedge funds and other non-bank speculators took big hits to their balance sheets.

But within this apparent madness, there is method. President Trump and his advisers are convinced that the US has been robbed of its economic power and hegemonic status in the world by other major economies stealing their manufacturing base and then imposing all sorts of blockages on the ability of US companies (particularly US manufacturing companies) to export. For Trump, this is expressed in the overall deficit in the goods trade that the US runs with the rest of the world.

Using a crude formula for each country (the size of the US goods trade deficit with each country divided by the size of US imports from that country, then divided by two), Trump’s team arrived at the tariff hikes for each country. This formula was faulty for several reasons. First, it excluded services trade, where the US runs surpluses with many countries. Second, a tariff of 10% was imposed even for countries where the US runs a goods surplus (this tariff remains in place). Third, it bore no relation to any actual tariff or non-tariff barriers that a country had on US exports (India has removed most of its). And fourth, it ignored the tariff and non-tariff barriers, of which there are many, that the US itself has on other countries’ exports.

Trump’s aim is clear. He wants to restore America’s manufacturing base within the US. Much of the imports into the US from countries like China, Vietnam, Europe, Canada, Mexico, etc., are from US companies based in those countries selling back to the US at lower cost than if they were based inside America. Over the last 40 years of ‘globalisation’, multi-national companies in the US, Europe and Japan moved their manufacturing operations into the Global South to take advantage of cheap labour, no trade unions or regulations, and the use of the latest technology. But what has happened is that countries in Asia have dramatically industrialised their economies as a result and so gained market share in manufacturing and exports, leaving the US to fall back on marketing, finance and services.

Does that matter? Trump and his crew think so. Trump reckons that imposing tariffs to force American manufacturing companies to return home and foreign companies to invest in America rather than export to it is the answer. He reckons that he can increase domestic manufacturing, reduce taxes for corporations and the rich, boost arms spending and cut government services and still keep the dollar stable – all with tariff hikes.

Is this going to work? No, for various reasons. First, retaliation by other countries will lead to a fall in US exports. In the 1930s, after the Smoot-Hawley tariffs were imposed, retaliation led to a 33% fall in US exports and spiralling down of international trade called the ‘Kindleberger Spiral’: a cycle where tariffs reduce trade, then retaliation reduces it further, then more retaliation, then first order effects on output, then second order effects, then more tariffs and retaliation, until global trade fell from $3 billion in January 1929 to $1 billion in March 1933.

Second, a tariff trade war now would hit the US economy harder than Smoot-Hawley in the 1930s, since trade is now three times as big a share of US GDP as it was in 1929. And third, falling trade growth from tariffs will lead to reduced international capital flows, weakening investment and economic growth globally.

Although the US still has the second largest manufacturing sector in the world at 13% of world output, after China at 35%,, US manufacturing employment has fallen sharply since the end of the golden age in the 1960s, mainly because US manufacturing profitability declined and technology replaced labour. Yet Trump’s team is talking about increasing manufacturing capacity at home through robots and AI and so delivering few extra jobs in the sector.

The reality is that Trump cannot turn the clock back to make the US the leading manufacturing economy in the world. That ship has passed. The manufacturing value chain is now global, with components and raw materials spread across the world. As the Wall Street Journal pointed out: “Even if US-manufactured exports increased enough to close the trade deficit—an extremely unlikely event—and if employment grew proportionately, our manufacturing-workforce share would climb only from 8% to 9%. Not exactly transformational.”

The US imports a lot of basic goods from China: 24% of its textile and apparels imports ($45bn worth), 28%of furniture imports ($19bn) and 21% of electronics and machinery imports ($206bn) in 2024. China actually has very little dependence on exports to the US. They make up the equivalent of less than 3% of its GDP. American consumers and manufacturers will suffer sharp rises in prices – and indeed that is the experience of previous tariff programmes.

Despite the inevitable failure of tariffs as a solution to re-industrialising America, Trump seems set on going through with his protectionist strategy. This can only be a trigger for a new slump both in the US and the major economies. It’s a trigger because already the major economies had been slowing to a crawl, even the US. Instead of hurting China, Trump’s tariffs will hit the US economy harder. US investment bank Goldman Sachs reckons that if the tariff war is sustained, China will suffer a fall of 0.5 percentage point in real GDP growth, compared to a forecast 5% this year, while the US will suffer a 2 percentage point fall on a forecast of 2.5% – in effect pushing the US into a slump.

This global trade war could not have come at a worse time for the British economy,. According to “Yanked away”, a paper by Simon Pittaway for the Resolution Foundation, UK labour productivity rose by a miserable 5.9% between the first quarters of 2007 and 2024. Real wages rose by an even more miserable 2.2% over this period.

In the 21st century, the UK economy has suffered a period of stagnation that has not happened since the 18th century! And now Britain’s largest trading partner, the US, is imposing a 10% tariff on all our exports there. If the world economy now turns down into a recession as a result of the trade war, particularly between the two major trading economies, the US and China, and financial markets panic, then the UK is ill-prepared to escape the consequences.

Michael Roberts worked in the City of London as an economist for over 40 years and has been a political activist in the labour movement for decades. He has written several books, including The Great Recession – a Marxist view (2009); The Long Depression (2016); Marx 200: a review of Marx’s economics (2018): and jointly with Guglielmo Carchedi as editors of World in Crisis (2018). He blogs here.

Main image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/145362372@N03/45116200775 Creator: Kevin Smith. Licence: Attribution 2.0 Generic CC BY 2.0 Deed