Mike Phipps reviews Voices against Putin’s war: Protesters’ defiant speeches in Russian courts, edited by Simon Pirani, published by Resistance Books.

As John McDonnell MP says in the Foreword, “It’s a humbling experience to read the statements in this book by heroes and heroines who have been willing to risk the full force of repression under Putin, in order to protest against the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the rise of oppressive militarism and the suppression of basic civil liberties.”

The book comprises speeches made in court by people who opposed Russia’s war on Ukraine, and were arrested and tried for doing so. Most of them are now serving long jail sentences. Many were savagely beaten and tortured before their trials, like Igor Paskar who twice lost consciousness during his interrogation, and Ruslan Siddiqi, who was electrocuted and threatened with being executed ‘while trying to escape’.

These individuals are just a fraction of the thousands detained by the Russian regime, many of whose whereabouts are unknown. The speeches here have become a powerful weapon under Putin, but they carry a heavy price tag. Three years were added to Andrei Trofimov’s sentence based solely on what he said at his first trial.

Others, such as Alexei Gorinov, a local councillor in Moscow who was arrested after making anti-war remarks at a council meeting, have had years added to their sentences, on the basis of testimony provided by prison officers, or prisoners terrorised by those officers.

At his second trial, he declared: “The real terrorists are those who unleashed this criminal war, this bloody butchery, as a result of which hundreds of thousands of people on each side have been killed and maimed. Those who really approve of terrorism are the propagandists of this war. They are the ones who should be on trial.”

Bohdan Ziza, a thirty-year old Ukrainian artist, poet and activist, was arrested in May 2022 after painting the colours of the Ukrainian flag on a municipal administration building in Crimea, which has been occupied by Russian forces since 2014. Convicted of ‘terrorist’ offences and sentenced to 15 years’ imprisonment, he said at his trial: “My action was a cry from the heart, from my conscience, to those who were and are afraid – just as I was afraid – but who also did not want, and do not want, this war. Each of us separately are small, unnoticed people – but people whose loud actions can be heard… It is better to be in prison with a clear conscience, than to be a wretched, dumb beast outside.”

Human rights campaigner Mikhail Kriger, 65, was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment for two Facebook posts. He told the court that Putin was a war criminal and a “treacherous tyrant who has usurped unlimited power and is elbow-deep in blood.”

Artist and musician Sasha Skochilenko, 35, protested against the invasion of Ukraine by replacing five labels in a St Petersburg supermarket with information about the war. She was sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment, but was released after eight and a half months in a prisoner swap. She subsequently wrote: “Pavel Kushnir was a musician who became a political prisoner. He died during a dry hunger strike in prison on the same day everyone celebrated my release. One life; one death. I am far from the best artist in Russia, I just happened to be the winner of the ‘Hunger Games’.”

Historian and political activist Aleksandr Skobov, 67, began his political activity in the left wing of the Soviet dissident movement in the 1970s. In the 1990s, he denounced the Russian war on Chechnya as a “war unleashed by Russian imperialism, with the aim of crushing the aspirations to independence of the peoples once conquered by tsarist Russia.” In 2024, he was charged with “justifying terrorism” in social media posts, and with “participation in a terrorist organisation”, thanks to his membership of the Free Russia Forum, an opposition group based in Latvia. From the dock, he denounced the Putin regime as “degenerates, scum, and Nazi riffraff.”

The youngest dissident represented here is Darya Kozyreva, 19, who was arrested on the second anniversary of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, for placing flowers, and lines from a poem, at a statue of Taras Shevchenko, Ukraine’s national poet. Charge with “discrediting the army”, Kozyreva commented: “My opinion is that, from the moment of the full-scale invasion, this army completely discredited itself.” She was sentenced to two years and eight months in a penal colony.

There are many more. Mikhail Simonov is a Russian citizen who lived in Belarus and worked in the restaurant car of international trains. He shared two news items about the Mariupol massacre perpetrated by the Russian army in Ukraine, and asked God to forgive Russia. Simonov was arrested when his train stopped in Moscow, and sentenced to six-and-a-half years’ imprisonment. He told the judge: “I always believed and now believe that human life has value that is unconditional.”

Journalist Roman Ivanov also denounced Russian war crimes in social media posts. Before being sentenced to seven years’ imprisonment, he told the court that he felt he had to speak out about the “criminal essence” of the war, “that it brings nothing but fear, pain, grief, destruction, loss – to another country and to our country too.” He knelt and asked Ukrainians’ forgiveness for his failure as a Russian citizen to stop the war.

The cases here are just one aspect of the Putin’s regime treatment of its opponents. Beyond its scope lies the blanket repression meted out to any resistance, however passive, across Ukraine.

The author estimates that repression in Russia is now in some ways harsher than at any time since the 1960s. The exemplary sentences handed out to some of the high-profile defendants highlighted here exceeds those given to dissidents in the late Soviet period. “It is no coincidence that statues of Stalin are again being unveiled in Russia,” notes Pirani.

But the opposition to Putin is also wide-ranging. Speaking recently of the dissidents highlighted in this book, Pirani said: “What is striking about these people is their diversity. They come from different generations, have different life experiences, and hold different political views.”

The book includes details of the prisoners’ support groups and how they can be contacted. To stay up to date with the Putin regime’s human rights abuses in Ukraine itself, readers should subscribe to the Ukraine Information Group’s weekly bulletin.

Mike Phipps’ book Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: The Labour Party after Jeremy Corbyn (OR Books, 2022) can be ordered here.

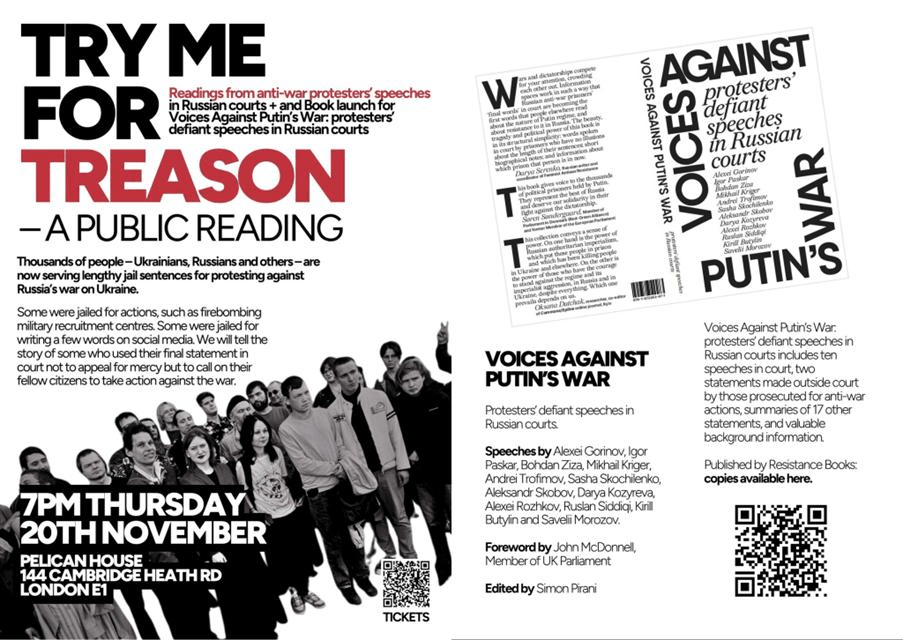

Thursday 20th November, 6.30pm: Try Me for Treason – readings of speeches from Russia’s courts / Book launch for Voices against Putin’s war. Pelican House, 144 Cambridge Heath Road, London E1 5QJ. Ukraine Information Group.

[…] out against Putin from the dock (Labour Hub, November […]