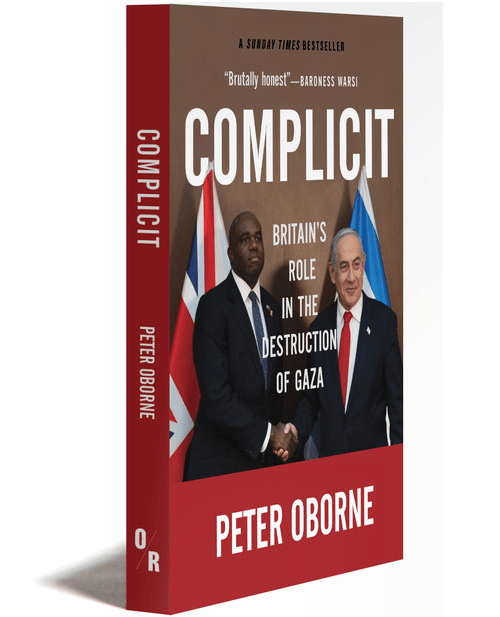

Mike Phipps reviews Complicit: Britain’s Role in the Destruction of Gaza, by Peter Oborne, published by OR Books, and Psychoanalysis and Genocide: Resisting Professional Complicity in Collective Trauma, by Martin Kemp.

British complicity in Israel’s genocide against Gaza has operated on many levels. First and foremost, it’s a bipartisan affair – from the Government and Opposition’s joint rejection of an immediate ceasefire after October 7th, to the support of both party leaderships to Israel’s cutting off of water, electricity and food to Gaza’s civilian population.

The complicity in Israel’s genocide runs beyond the main parties. Peter Oborne contrasts Britain’s outright rejection of South Africa’s detailed case against Israel at the International Court of Justice, with its readiness to accept Israeli allegations about the supposed involvement of UNRWA staff in the October 7th attack – Israel claimed ten members were implicated, out of a staff of 13,000 – on which basis the Government cut off all UK funding to the agency. In this, and its ongoing arms sales to Israel, the Government had fulsome support from much of our mainstream media.

Like the Opposition, they also failed to do their job properly, rarely challenging in interviews the Israeli ambassador’s “well-documented history of supremacist views and naked anti-Palestinian racism”; consistently operating a double standard in reporting Israeli and Palestinian casualties; and frequently displaying a combination of basic ignorance and outright bigotry – Oborne gives many examples.

The book probes – again in detail – the role of pro-Israel lobby groups in pressuring media organisations to parrot the Israeli narrative, as well as the BBC’s cowardice in failing to support its unjustly criticised journalists. This is controversial territory, as Oborne concedes: many mainstream commentators regard the concept of such an Israel lobby as an antisemitic trope. Oborne challenges this idea, suggesting the allegation’s effect has been to create an “omerta” around the topic, which helps explain why no mainstream media outlet would dare review the eminent Israeli academic Ilan Pappé’s 2024 book on precisely this subject.

Oborne is particularly scathing about the UK media’s glaring indifference to Israel’s killing of their reporter colleagues in Gaza. As Palestinian media workers were increasingly targeted by Israel, Labour Foreign Secretary David Lammy ignorantly claimed: “There are no journalists in Gaza.” According to Amnesty International, over 250 media professionals have been killed in Gaza since October 2023.

The pro-Israel political and media consensus meant that the vast majority of ordinary citizens who were appalled at Israel’s onslaught and wanted it to end were not only left without a voice: any attempt to mobilise for peace and highlight the plight of Palestinians was denounced as extremist or barbaric – “hate marches” in the words of then Home Secretary Suella Braverman.

Keir Starmer’s own position on the conflict, rejecting a ceasefire as Leader of the Opposition, meant putting to one side a career of expertise in human rights and international law, which had enabled him to mount a charge of genocide against Serbian forces in former Yugoslavia at the International Court of Justice a decade earlier. In contrast, his new-found reverential support for Israel was in lockstep with US policy.

But it also fitted the circumstances which had helped make him Party leader, where he and his advisors had “crudely exploited the issue of antisemitism in the Labour Party to aid their factional battle against the left… Together these dual motivations – external state and internal party – propelled Starmer into the moral abyss of aiding and abetting a genocidal onslaught against the Palestinians of Gaza.” It was the same mindset that led Starmer to excuse Israeli war crimes in a notorious LBC interview.

The damage done to the Labour Party by Starmer’s stance was severe. Resignations by Muslim councillors were sneered at by one senior Labour source as “shaking off the fleas”. But in the 2024 general election, the Party lost five seats to pro-Palestinian independents, including Jeremy Corbyn; and Wes Streeting came within 528 votes of being unseated by a Palestinian independent in Ilford.

In office, Starmer’s government continued UK military support to Israel, including hundreds of RAF spy flights, which may have made Britain complicit in war crimes. Starmer made no serious attempt to pressure either Israel or the US to stop the genocide – not even verbally condemning Israeli crimes or upholding international law. “Starmer’s complicity will stain his reputation, and Britain’s, for all time,” avers Oborne.

Oborne meticulously takes us through the disintegration of Israel’s case at the ICJ and the role of a compliant media in continuing to deny clearly substantiated atrocities by Israeli forces throughout the conflict. Opponents of their groupthink were routinely labelled antisemites. When the UN Secretary António Guterres criticised Israel for blocking humanitarian aid and was declared “persona non grata in Israel” by the Israeli foreign minister, the Daily Telegraph stated: “António Guterres needs to be replaced if the UN is to retain any shred of credibility.”

President Trump’s plan to expel all Palestinians from Gaza and turn it into a riviera of real estate opportunities opened a rift with the Starmer government, which began to distance itself from the expansion of Israeli operations. Starmer finally began to call for a ceasefire and what turned out to be very limited sanctions. The shift in line was due in no small part to the massive ongoing pressure mounted by millions of people who over the last two years have protested in many different ways against Israel’s war. The same movement impelled the 2025 Labour Conference to pass a resolution, despite the obstructive efforts of Party officials, clearly labelling the Israeli onslaught a genocide and calling for an arms embargo.

Yet the damage is done, concludes Oborne. Britain’s governing institutions are now indelibly disgraced. Worse, “any illusions that may have been harboured about Western commitment to moral or legal norms have been dispelled.” In short, by enabling this genocide, our leaders have created favourable conditions for others, some already happening, as in Ukraine, others yet to come. The increasingly lawless world we now face is something our own leaders helped create.

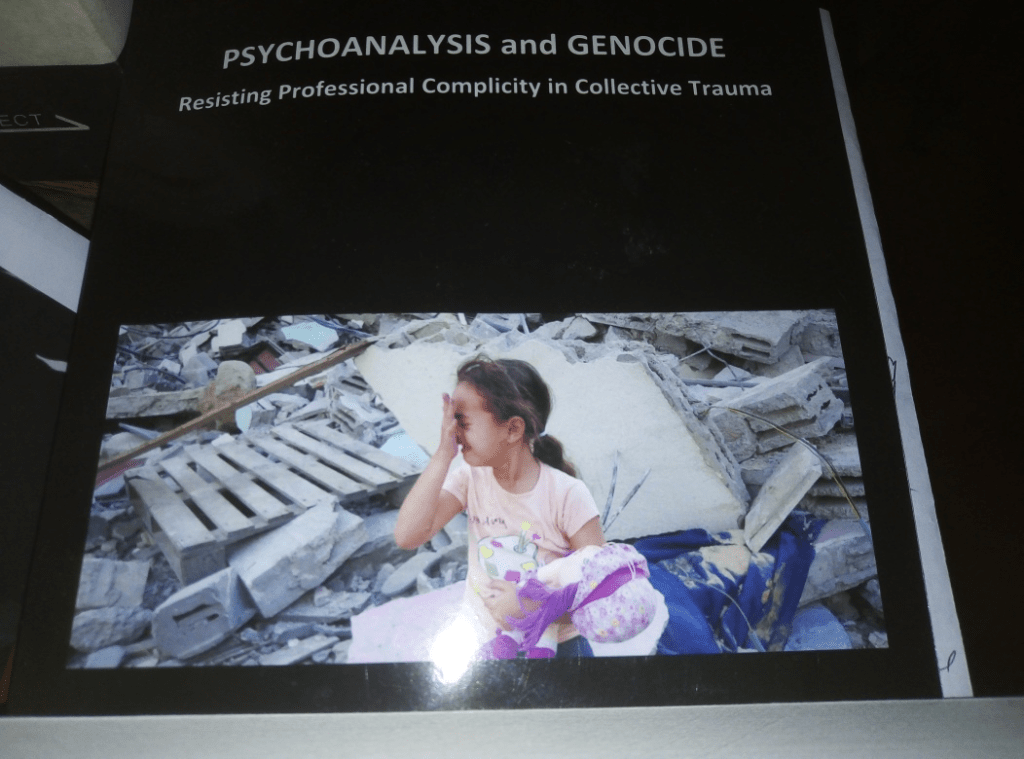

Psychoanalysis and Genocide

Similar themes pervade Martin Kemp’s Psychoanalysis and Genocide, a collection of articles by the eminent professional who has been involved with the UK-Palestine Mental Health Network since its inception.

He opens the book with a quotation: “You are asleep with your family. At 4am your house is surrounded by soldiers and border guards who hammer on the door and break the windows while you emerge, to be told you have 15 minutes to leave. Using whatever violence is necessary – against you, your wife and children – the bulldozer moves in… and you will be sent the bill for the demolition.”

The words are Salim Shraramweh’s and he should know – his house in Jerusalem was demolished four times. Flagged in the UK as an Israeli form of collective punishment against ‘terrorists’, home demolition is more a form of ethnic cleansing. Since 1967, tens of thousands of homes have been demolished in the Occupied Territories and only 5% had anything to do with security.

The psychological impact on family and neighbours, exacerbated by the fear of not knowing who will be next, is incalculable. Children are especially vulnerable – hundreds are in Israeli jails, often for throwing stones at Israel’s illegal Separation Wall. Their incarceration – and routine torture – is also less an issue of security and more a psychological weapon to break their resistance.

The level of continuing traumatic stress disorder among the Palestinian population is extraordinarily high. It fuels depression, other psychological conditions and drug dependency. Much of this book was written before the latest onslaught by Israel: the ongoing trauma will be felt for decades to come.

The destructive impact of the Occupation in Israel is less, but nonetheless noteworthy: a huge increase in violent crime, especially against women, juvenile crime out of control, a steep rise in anti-social behaviour.

But these trends will have a contaminating effect way beyond the borders of Israel. Indifference in the West to the genocide against the Palestinians cannot but encourage indifference to other genocides, invasions and other human rights abuses. The dehumanisation and racism necessitated by colonisation legitimises other forms of racism and extreme nationalism elsewhere. Likewise, impunity for Israel’s leaders fuels impunity for other aggressors – and all humanity suffers the consequences.

Raising these issues as a professional has been a frustrating experience for Martin Kemp. As he says in his Preface, “Faced with the moral dilemmas posed by tyranny, torture and other forms of state terror, now and historically, the foremost priority for the psychoanalytic establishment has been institutional calm, consideration of which trumps any interest in social reality, collective mental health or professional ethics.”

That mindset is seen in the refusal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research in 2016 and the International Association of Relational Psychoanalysis and Psychotherapy in 2019 to relocate their annual conferences away from Israel – despite the difficulties that Palestinian colleagues, who have a great deal to say about what was under discussion, would encounter in trying to attend.

The author cites many other examples of how attempts to raise the trauma of Palestinians within the psychoanalytical community has met with official responses ranging from complaints that this is excessively political to suggestions that it violates principles of non-discrimination, or that the implicit criticism of Israel constitutes antisemitism.

This evasion can be contrasted with the International Psychoanalytic Association’s October 2023 statement expressing horror at the “unprecedented” Hamas attack on Israel. While the attack was horrific and worthy of condemnation, it was hardly “unprecedented” in the context of much greater harm to civilians in Gaza – with far worse to follow.

Has ideological fixation distorted psychoanalysis? Kemp asks in conclusion. Sadly, the answer seems to be yes – and probably a number of other scientific disciplines too.

Mike Phipps’ book Don’t Stop Thinking About Tomorrow: The Labour Party after Jeremy Corbyn (OR Books, 2022) can be ordered here.