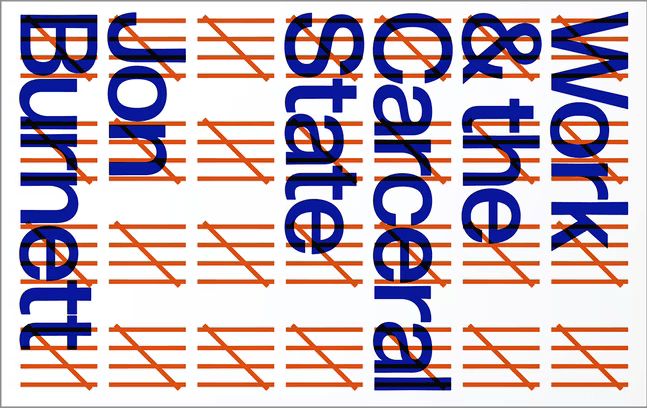

By Jon Burnett

By the beginning of this year, the Covid-19 virus had infected over 400 million and killed more than 5.5 million people globally. Separated neither from “the scourge of inequalities in wealth, income, and power that grew relentlessly from the 1970s”, nor the “destructive assaults waged by neoliberal capital on the welfare state and the ecosystem”, the virus was “deeply interconnected with the politicization of the social order” from its outset, as cultural theorist Henry Giroux has argued. And if, as he suggests, it is neoliberal capitalism that operated as a “petri dish for the virus to wreak havoc”, central to this was work and the social construction of labour markets and labour forces.

As in many other places, while the richest citizens in the UK were able to jet off to global playgrounds or otherwise shelter from its impacts from the onset, it is those deemed essential workers caring for the sick and the ill, keeping transport running, hospitals open, factories working, refuse moving, shops opened and items delivered in booming logistics services who have been among those most frequently exposed to the virus. Health workers, clapped at in 2020 by political figures who had just a few years earlier jeered when denying them pay-rises, were in some cases clapped to their deaths.

Many of those who have contracted the virus, in some cases fatally, have been unable to refuse work against the backdrop of levels of sick pay that have been described as among the worst in Europe, and have been found to be in breach of international law. It should not be forgotten that in January 2021, the 900 plus deaths per day meant that the UK had the highest per capita death rate in the world.

Unlike in many other countries, however, not that much attention was given to the manner in which prisoners within the UK were utilised as a labour force as the first of these lockdowns took place, with incarcerated people putting together PPE to mitigate the desperate shortages underpinned by a decade of austerity-induced vandalism to the NHS. This is not hyperbole. According to the British Medical Journal there were around 120,000 “excess deaths” between 2010 and 2017 as a result of the austerity measures and their associated NHS and social care cuts, taking place when Prime Minister (between 2010 and 2015) David Cameron was bragging of reshaping the state. He later said in his memoirs that he “probably didn’t cut enough”.

Thus, when the joint decision by the Justice and Health Secretaries to mobilise prisoners to scrabble together things likes scrubs and visors for healthcare workers in 2020, there was a bleak kind of continuity in the way the Health Minister championed this as part of a ‘national effort’ in combating the virus. For it echoed the ‘we’re all in it together’ narratives mobilised to justify austerity itself.

However, behind this appeal to national unity, what was – and is – embodied is something else: about the way in which prisoners can be and are utilised as labour forces to be mobilised (or tapped into) at points of crisis on the one hand, inserted within particular labour markets and discarded when no longer required, and the forces underpinning such labour itself on the other. What this embodied was something about a political economy of carceral labour, and about how it operates as a frontier of labour control central to the creation of institutional order. Moreover, it embodied something about the relationship between both.

New reserve armies of labour?

Understanding this requires understanding something about the resurgent commitment to carceral labour that has taken place over roughly the last decade, and its rationales, roles and functions. The entwining of work and punishment has a long history, of course: from banishment and transportation to houses of correction and the workhouse, England has ranked among the world’s pioneers. But when the Conservative Party returned to power in 2010 as part of a coalition government with the Liberal Democrats, it made no secret of its commitment to developing penal labour forces and markets in new ways, with the prisons minister Crispin Blunt boasting of plans to transform Britain into a “global leader” in encouraging businesses to make use of “effectively free labour”.

Just a few years later, ONE3ONE Solutions was established (named after the number of prisons at that point) to develop links and effectively act as a broker between prisons (and prisoners) and would-be employers: touting the benefits of incarcerated labour forces by claiming “our flexibility could be the strength you are looking for” and explaining that because of “ONE3One’s scale and diversity, we can support a wide variety of needs 24 hours a day”. And, given that the amount of work carried out in prisons increased by around 37 per cent in the years that followed, from 13.7 million hours in an ‘employment-like atmosphere’ in 2012-13 to 17.4 million in 2019-20, according to the Home Office, it is a message that appeared to have gained some traction.

Between 2016 and 2019, contracts totalling more than £23 million were brokered to utilise prison labour in England and Wales, ranging from call centres to woodwork and from engineering to agricultural work. At the same time, these existed alongside a separate set of contracts within which prison work has been used as a labour force for the state, in a range of contexts ranging from making equipment for the military and the Ministry of Defence to the infrastructure within prisons themselves.

Or to put it another way, that prisoners could be rapidly mobilised to put together protective equipment for healthcare workers was in part because the decade previously had been spent developing the infrastructure – from workshops to equipment, to brokering systems – through which such rapid mobilisations could be facilitated. According to ONE3ONE’s publicity material to potential employers, this is “justice working for you”.

However, if this is in some ways indicative of the substantial efforts and investment in developing the capacity for carceral labour, what it further points to is something else. Resurgent initially at a point where the austerity measures were coalescing with a full-on violent and regressive attack on the principles of welfare – not least with an intensified commitment to fostering ‘workfarism’ – prison labour has operated as part of broader attempts to recalibrate supplies of labour at points of labour market restructuring. And as such, it is not unimportant, for example, that when the infrastructure for prison labour was redeveloped further in 2018, with a new strategy (and new body replacing One3One Solutions) launched by Justice Secretary David Gauke, he suggested that Britain’s vote to leave the European Union two years earlier was an “opportunity [for] both prisoners and employers”.

For, while he suggested employers would be “better able to fill short-term skills gaps whilst also developing potential permanent employees for the longer term”, with the government committed fully to a labour market model within which units of labour can be hired and fired at will, this might otherwise be seen as part of attempts to reduce one labour stream within it through immigration policy, whilst simultaneously attempting to facilitate others through welfare and criminal justice policy.

Indeed, the fact that calls from industry leaders in summer 2021 to utilise people in prison to mitigate labour shortages would come most vocally from sectors which have historically built business models around migrant labour is revealing. For in the absence of raising working conditions, people in prison might well be one way that certain employers can get close to replicating the disciplinary power of immigration status itself.

Work and the carceral state

That this is the case is down to how these advantages for employers are structured politically and fostered institutionally. The vast majority of those who work in prisons work for massively suppressed wages, and with little ability to negotiate working conditions or terms. Bound tightly to an Incentives and Earnings Policy framework which rewards and punishes behaviour, as well as in some cases operating as a de facto form of currency by determining access to finances and making available (or not) small privileges, such as time out of cells or having additional visits, this operates as a powerful form of labour control in 21st Century Britain.

For ‘transgressions’ in the labour process, such as being removed from a job or organising around working conditions, can result in the rowing back of these meagre privileges and in some forms their removal. Indeed, while prison labour is often depicted in liberal discourse as a way of providing skills and experience – and while prisoners, it is important to point out, want to engage in meaningful activity – what cannot be escaped is that this facilitates labour forces frequently denied in real terms the rights and protections that have been built up over centuries of organising, and which everywhere are under attack. Or to put that another way, the forms of labour control within prisons are connected directly to their utilisation externally, because at least in certain contexts it is these forms of control which make prison labour so attractive.

At the same time though, if this is indicative of the manner in which a political economy of incarcerated labour is linked to its institutional utility, this cannot – and should not – be dissociated from the broader functions of the prison, and where it is situated in an expansive carceral state. For, as criminologist Joe Sim has argued, prisons operate as warehouses for the “churning” of those whom “the pliers of punishment, and the laser of criminalisation, reach deeply into their lives and have become normalised”: the “vast, increasingly racialised, numbers of the dispossessed, pauperised and destitute”, who are frequently sucked into their orbit.

And against this backdrop, while some of those working in prisons are tapped into as labour forces, it must be remembered thatwork is not the dominant experience, and many others who work do so labouring to in the upkeep of prisons themselves – as cleaners, wing workers, in kitchens and so on. That is, their labour is utilised in the reproduction of their own incarceration.

As such, this raises questions fundamental to the labour movement and beyond.As is very well-established, the UK has the third highest prison population when compared to other European countries. But if the vast form of carceral inflation which saw this double between the early 1990s and 2010s was overseen by Conservative and New Labour governments alike, the current Conservative government is clearly gearing up to take this even further.

As just one indication, in February 2022 Deputy Prime Minister Dominic Raab elaborated the government’s plans for what he described as an “unprecedented prison-building programme” in the next few years: the “largest in more than a century” and part of a broader £4 billion attempt to expand the prison estate by 20,000 places.

Building on ideas set out in the government’s 2021 Prisons Strategy White Paper, prison labour is central to this strategy, ‘putting more offenders behind bars … and training them for release,” according to Raab. While at the same time, when set alongside the plans to recruit 20,000 more police officers, to expand police powers, to increase prison sentences for certain offences, to create new forms of offences, and more, while simultaneously eradicating the legal mechanisms used to hold state power to account, there is no ambiguity whatsoever that this is a prisons strategy driven by plans to fill these new places through intensifying criminalisation and state power. We only have to look at the Police, Crime and Sentencing Bill worming its way through Parliament as an indication of attacks on the right to organise and more broadly against racialised and working class communities.

Similarly, the Nationality and Borders Bill presages a ramping up of open warfare on migrants and asylum seekers, including, but certainly not restricted to, the greater use of prison sentences and quasi-forms of detention to exist alongside immigration removal centres. Indeed, in the latter case many detainees work in internal labour markets, generally paid £1 an hour for things like cooking and cleaning institutions managed by some of the largest companies on the planet.

The struggle, therefore, must be multi-pronged. On the one hand, it is imperative that the labour movement works in solidarity with incarcerated workers, and that this solidarity incorporates issues including working conditions, regulations, broader labour protections and wages. But on the other, this must operate in tandem with a broader move to dismantle the carceral state, including by resisting liberal ideas of reform which serve fundamentally to secure its expansion.

While prison labour is held up as central to ideas of “rehabilitation revolutions” or “healthy prisons”, for example, as criminologist David Scott has pointed out, it is essential to remember that prisons fundamentally exist as institutions which are designed to “inflict pain and suffering” and are “characterised by institutionally-structured violence”.

Prisons are “places that take things away from people”, he continues. “They take a person’s time, relationships, opportunities, and sometimes their life. Prisons constrain human identity and foster feelings of fear, anger, alienation and social and emotional isolation.” As Angela Davis states, it is necessary to build the conditions whereby they can be rendered obsolete.

Jon Burnett is a lecturer in Criminology at Swansea University. He is the author of Work and the Carceral State (Pluto Press, 2022).